The Speaking To Memory exhibit at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology showcases testimony, government documentation, photographs, and formal appologies on behalf of church, police, and state, regarding the Residential school system in Canada, and more specifically, the people affected by attendance at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School at Alert Bay, British Columbia, during the late 1930s. The Truth and Reconcilliation Commission, with a budget of $60 million over 5 years, has been in the process of gathering the information, along with testimony from those affected by the atrocities commited at the Residential schools, with the mandate of sharing experiences and creating transparency around the dark history of Canada’s past in order to form strong relationships through reconciliation.

What struck me initially were the quotations from Duncan Campbell Scott, Canada’s Indian Affairs minister circa ______, and other government official statements, superimposed on images of the St. Michael’s school in its current state. These images really prepared me for the rest of the exhibit; they introduced the motivations and intent behind the Residential school system while also reminding me of the comprehensive human rights violations and unspoken failures that came about with them.

On the other hand, these images also served to guide my response to the exhibit. When I came to the short testimonies thumb tacked to the North wall, and found several which claimed nothing bad had happened to them at the schools, and that they had valued their experiences from their childhood as positive and affirming, I was shocked. I expected all of the testimonies to be filled with anger, frustration, pain, and sorrow. When they weren’t, I almost wanted to reject them as untrue. These positive statements broke my expectations of what I would expect from victim testimony, and in the process expanded what I found to be acceptable conversation concerning residential schools. While these positive testimonies may have been strategically placed for contrastive effect, and while their positive experiences may have been gleaned from the ignorance of the brutality others experienced, it was provoking to see them in the context of the exhibit. This is the value I found in the Speaking To Memory exhibit–that Aboriginal people be given a choice to have their voice heard, and their stories expressed, whether or not they follow the expected narrative line.

The publicly viewable comment book, the anonymous comment box, the photographs (where one could write in the names of any of the children they knew), and the chalk board wall were all very interesting ways of inviting response, both physically and mentally, especially within the climate of a Museum where one typically finds themselves attempting to walk through silently and without touching ANYTHING. These mediums for conversation also prompted me to analyze the types of responses one would typically feel responsible to contribute. Many simply said, “This is sad/terrible/horrible/regrettable…” etc. But there were also many responses from children who, being so young, took the opportunity in the comment books to draw pictures, some (accidentally?) sad, while others were silly and almost joyful.

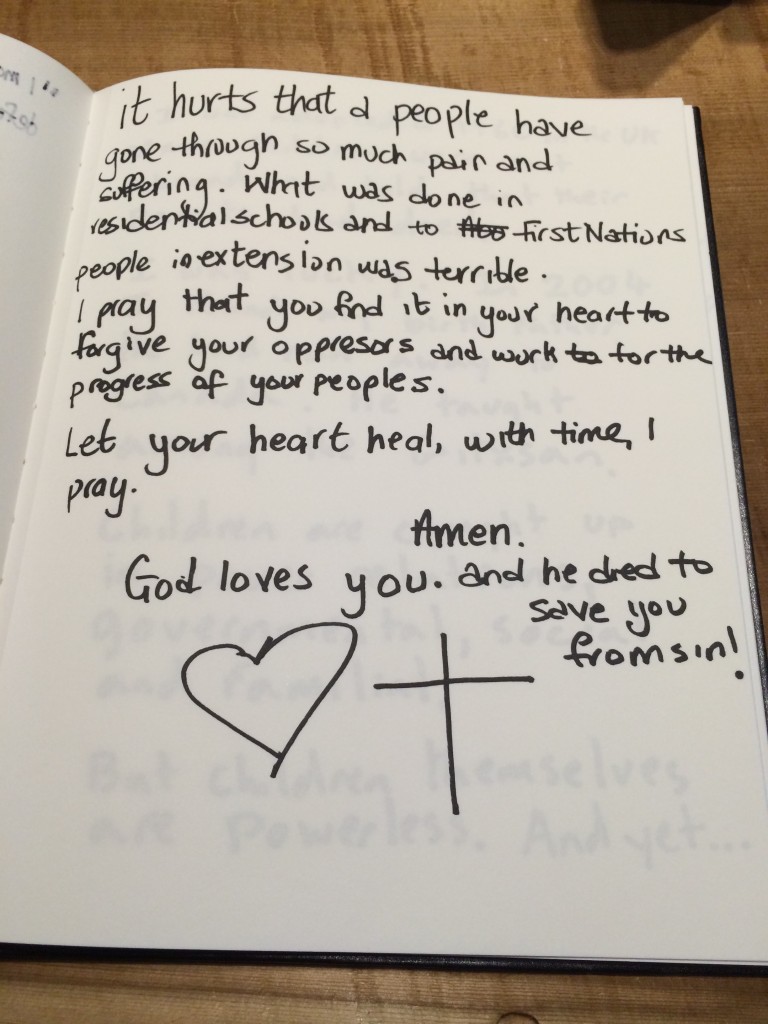

And then I came across this comment.

While I obviously want to steer clear from any unjustified criticism of a religious institution, it seemed uncomfortable to me to read this comment, so much that I photographed it to consider now. It was interesting to have just finished reading formal apologies issued by church officials that were hung on white scrolls in front of floor to ceiling windows, and then to come across the sentiment: “God loves you, and he died to save you from sin!” It seemed to me that much of the pain that was caused in these schools was the complete disregard for indigenous cultures and the imposition of white, colonial, christian doctrine on groups of people that did not need God’s saving…they needed respect, dignity, agency, autonomy, and empowerment. But then again, this comment is not responsible for what has happened, or continues to happen in regards to indigenous people all around the world. It does, however, when used in the right context, with open ears, and with the right intentions, and actions to follow, contain the potential to help reconcile the human rights violations experienced by Aboriginal people at the hands of colonialist oppressors.