Every day, we are faced with situations that require us to make compromises in order to achieve our goals. It could even be as simple as waking up late one morning and rushing to get to work on time. With only 15 minutes to get ready and out the door, you would probably opt for a simple breakfast like jam and toast rather than bacon and homemade waffles. Currently, we are facing a similar issue with our community project. After getting our project proposal feedback, our team had to re-evaluate how we would go about achieving our project goals with the time left in the term. As mentioned in our previous post, our plan was to finalize our survey and collect responses during the Sustenance Festival at Hillcrest Community Centre in addition to sending it out to the community garden mailing list through Joanne MacKinnon. Little did we know, this would be harder than we thought with just a little over a month left in the course.

What?

Even in the lobby of a busy community centre in the heart of Little Mountain-Riley Park, we only managed to get less than 30 survey responses in 4 hours, and that was with the incentive of a chance to win a Nester’s Market gift basket. Our survey can be viewed here. The vast majority of survey responses indicated that participants were not interested in renting a community garden plot. With the slow response rate and low level of interest, it is hard to imagine that we will have enough information before we have to start writing our operations manual guidelines and final report. Even with online responses, we cannot guarantee that a survey alone would be enough to get an idea of community preferences. We need to think of an alternative.

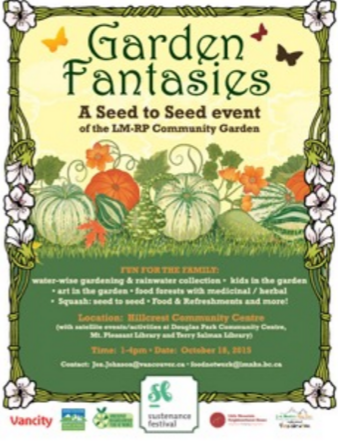

Group 10 collecting survey responses at the Sustenance Festival. The event took place on October 18th at Hillcrest Community Centre.

So what?

This week in class, we listened to Dan Barber’s story about how he tried to replicate the complex but ethical method of raising geese for foie gras. Dan Barber is an established American chef known for his use of “farm to table” cooking and dishes that accentuate the natural flavours of fresh, seasonal ingredients. When he met Eduardo, the man who mastered the technique of raising ethical foie gras, he couldn’t believe that everything from the type of grass the geese ate, to the climate, mating, and overall freedom, were factors that contributed to the superior foie gras flavour. Even after years and years of trying to replicate this process in New York, his efforts were unfruitful. Eduardo’s technique probably did not happen overnight, and most likely required years to perfect. Similar to our food-hub model, sometimes we just can’t expect success to occur immediately. It is easy to get swallowed up in the complexities and size of a project, which could lead to overwhelming stress. In these situations, the project scope needs to be adjusted to manageable parts that can eventually be integrated to create the final product. We do not want to compromise the quality of our project by biting off more than we can chew.

Now what?

After discussion with Joanne and the teaching team, we agreed that it would be best to start the survey process, but leave the data analysis for the next LFS 350 groups. That way we can focus on other parts of the operations manual while survey responses can continue to be collected online until an adequate sample size is reached. We realized that surveys are rather limited in the information they can provide. No matter how well a survey is designed, obtaining useful data is highly dependent on whether people choose to participate or not. At the Sustenance Festival, most people could not be bothered to answer 6 questions. Luckily we met Varouj, a landscape architect and LM-RP Food-hub planning committee member. He was very interested in how we planned to incorporate our data into the operations manual. He also suggested that we contact other community gardens directly about how they have divided their plots among groups, individuals, and public commons, as an alternative to solely relying on the survey. This way, we can base our recommendations on what models are already known to work well. One of the significant moments this week was when Varouj suggested to work backwards and develop a “mind map” of events. For our complex system model, which involves the City of Vancouver, the LM-RP Neighborhood Food Network, funding, building contracts, grants, and much more, the path to the functional food-hub is not a linear one, but rather a winding, branching pathway with no singular “right” way to go. Realistically speaking, we can’t take this on all our own. We need to rethink our data collection methods and the parameters of our operations manual. One recommendation we got from the teaching team was to write an outline with recommendations and not a full-length operations manual. As outsiders of the community, and limitations in our experience and time frame, we need to step back and think of what is a reasonable amount of work that can be a positive contribution to the project overall.

It is ultimately a process that leads to another process. A system has many changing and moving components, and it is too easy to get swept up in the complexity of things and give up.

Our strategy for dealing with the overwhelming feeling of “scope-creep,” is to take things one step at a time and focus on a few components and do our best to make deep inquiries that can help the LM-RP Food-Hub project along.

A valuable lesson we learned during the Sustenance Festival was that the method of data collection for complex systems cannot always be confined to the limits of an online survey. As science students, we have become used to using the controlled methods often employed in scientific research. The importance of personal dialogue with community members has given us a better understanding of what people value.

References:

Glass, I. (2011). Poultry slam 2011 – act 3: Latin liver. (Radio Archive).This American Life.