Executive Summary

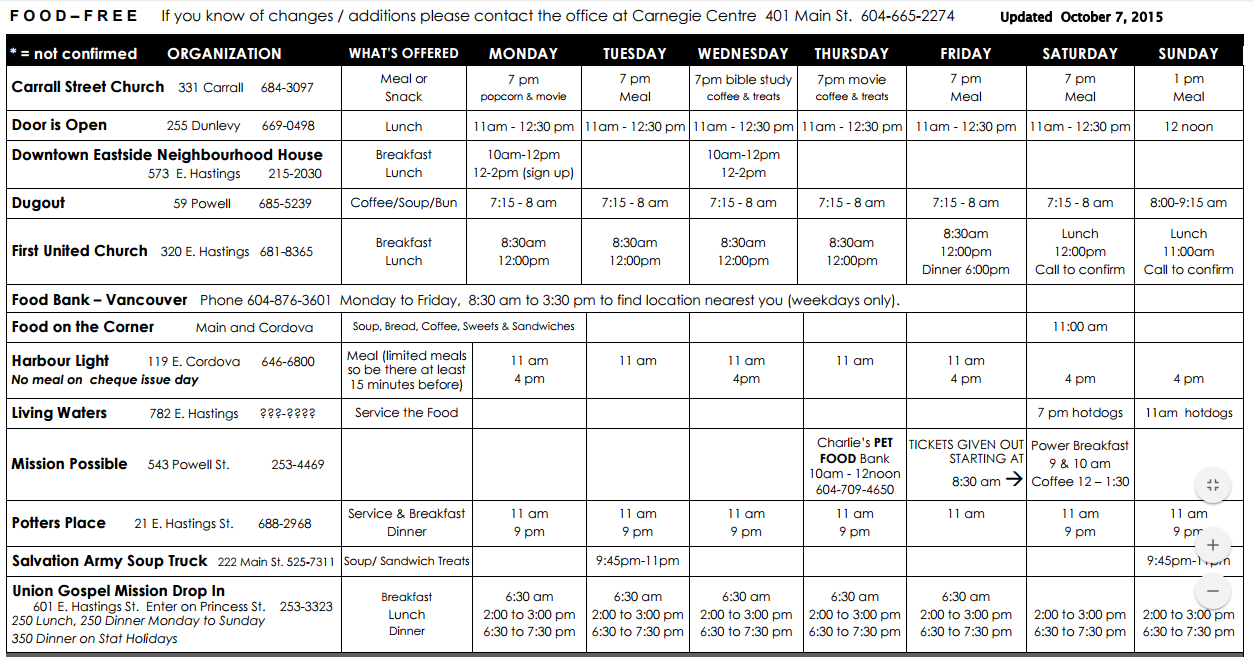

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) has long been infamous as the most vulnerable neighbourhood in the city with many of its residents struggling with poverty, mental illness and drug addiction. There has been extensive research done in this area and our group project’s objective was to fill in some of the existing knowledge gaps in this research and verify information about community resources. To accomplish this we used an asset-based assessment (Mathie et al., 2003) of the food resources available within this neighbourhood to answer our inquiry questions: 1) What are the food resources available to vulnerable populations and where are they located? 2) How accessible are they in terms of hours of operation, disability access, locations, signage and who they choose to serve? 3) What is the nature of the programs being offered? 4) Does the location, accessibility and programming reflect what is advertised in already-existing community food asset resources for the DTES?

By focusing on the assets within the community this approach presents a positive and uplifting picture for organizations and residents of the DTES. The creation of a food asset map renders the neighbourhood more accessible to vulnerable populations. An extensive online review of available information on these food resources was the primary means to answering these questions and discovering knowledge and service gaps. These findings were then narrowed down through observation, ground-truthing and phone interviews. The research confirmed that a large number and variety of charitable organizations cater to vulnerable populations in the DTES with some offering additional services. We also discovered that the information currently available online about these organizations was often inaccurate and a fully researched map of the area’s free and low cost food resources was not available. In completing our research several functional gaps were discovered. They were mostly due to lack of communication, resources or the visibility of organizations, which can easily be addressed in an asset-based community.

In the future our recommendations are that organizations work in concert to address potential service and knowledge gaps using the resources that already exist. Many charitable organizations individually struggle due to a lack of resources and donations which could be addressed locally. There are numerous organizations providing food for a variety of target groups which is advantageous. However, there are often several organizations assisting the same population so other groups may be missed. Overall, the DTES has many resources currently in existence that make it a good candidate for continued asset-based development.

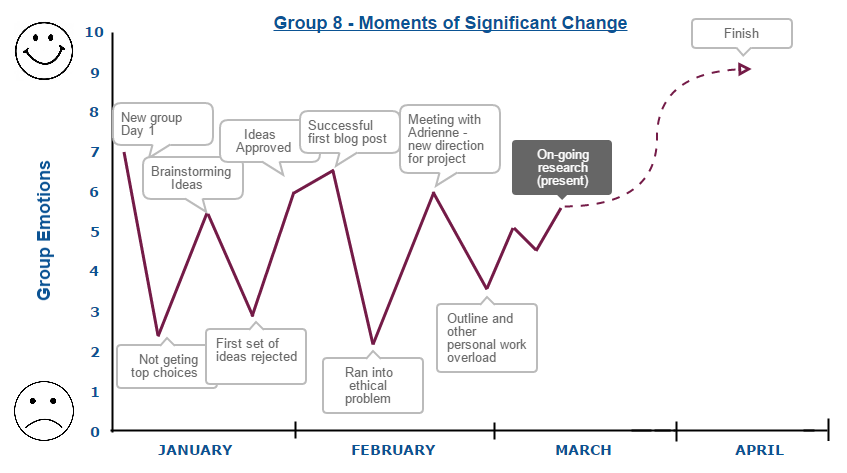

Moment of Significance

What?

During the past week we had both positive and negative significant moments. The positive part includes visiting the community centers within our predetermined boundaries in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES).The main purpose of this visit was to make sure that the physical addresses of the centres matched what was presented online, to check they still exist and to gather additional information about organizations.This visit to us was a turning point which relieved lots of our stress as it cleared up many uncertainties towards reaching our goal. The only negative side to this visit we felt a little bit unsafe walking down the streets and there were a lot of drunk people trying to talk to us.

From our research concluded that there are definitely some gaps between these centers that can be improved with a thoughtful plan using assets that already exist. These gaps include: timing of meal operations, minimal signage and advertisement to let people know these centers exist, as well as poor food quality.

We further completed our research by phone calls and asking pre-approved questions in term of ethics. This was definitely positive as most of the centers answered our questions kindly and we could gather good information. Lastly, our most significant accomplishment was being able to make our asset map which we believe was done efficiently and effectively as a team

Our negative significant movement started when one of groups members stopped communicating or participating in any group works. This might not seem a big concern since one might think since her work will be divided by three, it should not add up so much to our work load; however, this extra coverage was a huge setback with all the other workload from our other courses. Not being notified if our group member will participate or not until the last minutes made everything worse and more frustrating. This caused a higher level of stress, as the deadlines are just around the corner and we need to prepare for our finals as well. Even though we tried to come up with a good plan to divide up her work, we are still concerned not being able to cover her parts as perfectly due to lack of time.

So What?

The importance of completing the groundwork and phone calls is that it allowed us to verify and fill in any missing information from our online research and help us obtain accurate and updated data for our map. While completing our groundwork, we did feel discomfort at times travelling on foot through the downtown eastside as only a pair. This is because the sidewalks were crowded and narrow and we sometimes had to cross the street in order to walk around large groups of people to feel safer. We feel that having an extra group member with us would have made it more comfortable as it is safer to travel in a bigger groups. With a bigger group we could also benefit from more flexibility such as scheduling more trips for footwork as different subgroups, as well as taking more time to call back some organizations for gathering more comprehensive information. Missing the help of a group member significantly affects our capacity and efficiency for gathering information via groundwork, phone calls, and online research. These are some of the negative effects that our group noticed when a member stopped communicating and participating in group work.

We have done our best to adapt to this predicament by splitting up work as fairly as possible between the three of us. Each of us recognize that this project-based course deals a fair amount of work, and to manage it we keep ourselves organized using a series of group deadlines, which can sometimes look overwhelming. The workload may have been a contributing reason for our group member to lose motivation and vanish. However, this is precisely the reason for working together in groups, so that greater goals can be accomplished using the combined expertise of individual members (Haller, Gallagher, Weldon, & Felder, 2000). An essential factor which (Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1991) proposes for successful group work is to hold one another accountable for individually assigned work. When a member stops being accountable for their portion of work, the extra workload becomes particularly strenuous on the rest of the group members. This produces feelings of frustration and bitterness, which we definitely sometimes sensed. We feel that holding more frequent meetings in the early stages of our project may have helped to improve accountability, by reinforcing group cohesion and motivation.

Now What?

With our research findings we will be able to complete our project objectives and present a completed map. The broader issue involving the map is to keep it current so we will not mislead the public we are trying to assist. Continuous updating will be required, should another group take on this project next semester. A positive consequence of this action was a sense of accomplishment as a self-propelled idea was successful. The final step will be to explain our accomplishments in our final report document.

In reference to our negative significant moment, we are taking a proactive approach. At the beginning we decided to maintain frequent communication between all members as well as stay organized so that deadlines were met. Now that our group has decreased by one member, these two things are even more important as is moving on to the best of our ability.

With this group member not contributing or communicating came feelings of frustration, anxiety and a higher level of stress. In order not to remain trapped in frustration, we as a group had a conversation about how we were feeling and how to productively deal with the situation. After making some concrete decisions about participation and having a meeting with our teaching assistant, we moved on to resolving the situation practically. We had to act quickly in order to complete the presentation as the deadline was in a couple of days. We immediately went about splitting up the work originally assigned to the former group member, ensuring each person could handle the amount given to them. We set up another meeting before the presentation was due to make sure we were all on the same page. The same challenges will be faced for the final project report and handled through hard work and organization.

The broader issues that need to be considered in completing the final report are: not overloading one person with all of the extra work and dealing with the decreased amount of time available to each of us as finals approach. Our deadlines and distribution of work will be decided as a group and open conversations will be encouraged so that if people are feeling overwhelmed, others can assist. Time management will be essential both individually and as a collective to submit our work on time while attending to our other studies.

The quality of work may suffer slightly as time and now resources are limited. It is likely that our level of stress and anxiety will increase as the deadline approaches making it challenging to stay focused. While it is not necessarily effective to work at something until the last minute, this may be a challenge we have to face.

It has been challenging to face this unexpected obstacle when nearing the end of our project however the remaining members are committed to producing a quality product and report.

References

Haller, C. R., Gallagher, V. J., Weldon, T. L., Felder, R. M. (2000). Dynamics of peer education in cooperative learning workgroups. Journal of engineering education. 89(3). 285.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Smith, K. A. (1991). Cooperative Learning Increasing College Faculty Instructional Productivity. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4. Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

Mathie, A., & Cunningham, G. (2003). From clients to citizens: Asset-based Community Development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in Practice, 13(5), 474–486.