I have chosen to do an analysis of a few of the characters that we are introduced to during pp. 18-28, as this passage contains numerous historical and literary references. Some can be seen in the names of Alberta Frank, Henry Dawse, and Babo Jones; three characters that I found to impactfully set a foundation for a deeper reading of the novel.

Destabilizing Alberta Frank

In this chapter, we are introduced to Alberta Frank, a Blackfoot woman and university professor at a university in Calgary. As Jane Flick notes, the professors name suggests the Canadian province in which she is teaching. Alberta is rich in history and culture from various Indigenous groups, including the Dene of the subarctic north, Woodland Cree of the boreal forests, Blackfoot of the southern plains, and Metis people throughout. Flick also points out that Thomas King may have drawn the name from Frank, Alberta, a small town on the turtle river that was devastated by one of Canada’s most deadly landslides in 1903. Leading up to the slide, the geological layers of the mountain became increasingly unstable over time as water seeped into the mountain, eroded the limestone, and created an unsettled structure of rock masses. Thus, it was only a matter of time before sudden disaster struck.

This kind of building tension can be seen in Alberta Frank’s life, beginning with her apparent dissatisfaction during her lecture in this passage, during which she provides fairly blunt responses to her students and sighs at the responses of Henry Dawse (King 20). Beyond this passage we learn that this divorced professor longs to be a mother without any kind of long term relationship, haunted by her childhood abandonment by an alcoholic father and her marriage to a stereotypical white man. She aligns her outlook on marriage with her hatred for flying, as both leave her feeling “helpless” and “completely oblivious to impending disaster” (King 85). Further, Alberta portrays her ex-husband Bob as a figurative colonizer, as their marriage consisted of him trying have her support him financially and avoid “[spending] the rest of [her] life in a teepee” (King 86). This past trauma clearly affects her ability to accept any prospective relationships, and leaves her distrustful of conventional marriage and family structure. Unsurprisingly, she finds herself stuck between her romantic involvements with Lionel and Charlie, balancing the two in order to avoid any serious committments. As the tension in her personal life continues to build, the crisis finally unfolds with her mysterious pregnancy and it seems to be no coincidence that this closely corresponds to the timing of the dam breaking. It may potentially represent the physical aspect of a figurative cleansing and renewal of the internal conflicts faced by each of the characters, enabling the novel to conclude while structured around new beginnings.

“She was helpless…. Completely oblivious to impending disasters. Marriage was like that” (King 85)

The Ignorance of Henry Dawse

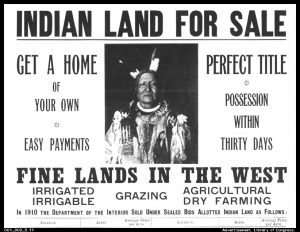

During this passage we are also introduced to a few of Professor Frank’s students, including the inattentive and seemingly lazy Henry Dawse. He is used in the novel as a target of humour, revealing King’s views on a historically well-known U.S. senator with the same name. Jane Flick also notes this connection, describing the character as a reference to the Dawse Act of 1887 that was written by Senator Henry Dawse. This passed after his advocacy for granting land to Native American individuals in exchange to renunciation of tribal allegiances, and resulted in over 90 million acres of tribal land being taken from them and sold to non-Natives. The act allowed the federal government to take tribal land and break it up into individual plots that would be given to Native Americans if they took U.S. citizenship, furthering efforts of forcing non-settlers to become part of mainstream U.S. society. Despite his career of actively seeking their assimilation, Dawse was not well known for being particularly well educated about Native Americans.

Considering this, it is not surprising that the Henry Dawse of the novel acts careless about the lecture on the southern Plains tribes, and would rather sleep through much of it. When he wakes up towards the end of the lecture, he reveals his ignorance regarding Native American culture, describing the drawings of the prisoners as “not very well done” with unusual colours “like kids drawings” (King 20). It can be said that Henry displays a similar lack of care and respect for non-settler culture and history as his historical counterpart, and thus, reflects how this perspective lives on in contemporary times. He also functions to introduce and highlight a very significant legislature-enabled oppression of Native American Indian culture, that is considered further later in the novel.

“An Act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes.” An excerpt from the Dawse Act of 1887 (linked above).

Babo Jones and the Ship

The scene that introduces us to Babo Jones coincides with an introduction to Sergeant Cereno, and as Jane Flick points out, this seems to be no coincidence. In Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno”, Babo is a black slave on board the San Dominick who leads a successful revolt against the sailors. Benito Cereno is the Chilean, Spanish-speaking captain of the ship, over which Babo gains control and redirects to Africa for freedom.

This pattern of over-turning a power dynamic is seen between these characters in the novel, as Babo repeatedly ignores the Sergeant’s questions and pursues her own asides or even questions him instead. She alludes to the literary reference of Cereno’s character, asking if his name is “Italian or Spanish or what?” (King 25). Further, allusions to her connection to a ship are seen in this passage, such as her carrying life saver candies (King 24) and describing her Pinto car as looking like a ship (27). The literary references represented by Babo and Cereno alongside their dysfunctional and unproductive dynamic, functions to represent the white-colonizer perspective of non-settler cultural groups, and to promote more equal consideration.

Works Cited

“Aboriginal Peoples of Alberta: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.” Alberta Government. Web. https://open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460113080. 18 March. 2020.

Flick Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. March 18h 2016.

Getchell, Michelle. “The Dawse Act.” Khan Academy. Web. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/the-gilded-age/american-west/a/the-dawes-act. 18 March. 2020.

“Henry Dawse.” Spartacus Educational. Web. https://spartacus-educational.com/WWdawesC.htm. 18 March. 2020.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

“Melville Stories.” Sparknotes. Web. https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/melvillestories/section6/. 18 March. 2020.

Morton, Ella. “The Dramatic Remains of Canada’s Deadliest Landslide.” Atlas Obscura. Web. http://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obscura/2014/04/08/the_1903_frank_rockslide_in_alberta_canada_is_the_country_s_deadliest_landslide.html. 18 March. 2020.