In hopes to reduce traffic congestion in Melbourne, the Victorian Government has passed a parking levy in January of 2006 on busy parking spaces located in the city. The purpose of introducing this levy by the government was to target those drivers that use all-day parking and to discourage them from driving during peak hours as a means of reducing congestion on the road. This levy covers three types of parking on the street: municipal, commercial, and private as well as non-residential parking. Municipal parking applies to any parking that is supplied by the city for local drivers in the city, whereas commercial parking applies to those parking spaces that has an actual ownership and is provided to customers utilizing their service, as such parking in a restaurant’s lot. Thirdly, the private and non-residential parking are those off-street parking spaces that are reserved for certain owners, such as tenants reserving them for their employees to park. When implementing this levy, the government had forecasts of generating annual revenue of $40 million, which the income will then be transferred over to improving public transport in metropolitan Melbourne [1].

Like any policies, there are typically exemptions and it is no different in this case either. Residential spaces are exempted from this levy, such as parking spaces for guests and visitors, loading docks, motobike parking, vehicles displaying a disabled-sign, and free parking that may be provided by the owner as the owner would pay the levy in such cases. So essentially this levy was designed with the the target as drivers who require all-day parking in mind, to achieve reducing traffic congestion in the busiest parts of the city. Furthermore, with the levy implemented, drivers would be encouraged to not park all day and thus the supply of short stay off-street parking would be indirectly increased and these generated incomes can then fund better public transport. In a way, the people that would experience the greatest impacts from this levy would be those who drive and work in the downtown core, requiring to park all-day. As a result from this levy, owners of car parks will be charged a flat annual rate of $400, which got increased twice the amount to $800 in 2007 after the first year of implementation [1].

Observing the responses of car park operators to the levy, some of them chose to discriminate against their customers by passing on the cost to only the short-stay ones rather than to their early-bird and all-day customers. On the other hand, some operators decided to partially absorb this levy cost themselves. So in a way, this levy was not implemented appropriately because it led to discrimination in how the costs of congestion are mitigated overtime. Thus, instead of effectively reducing traffic congestion and reducing costs, the levy re-organized how the costs are distributed, whereas the drivers who needed parking in the downtown core areas had to pay for them.

Revenue was indeed generated through this implementation, but cost was not reduced and congestion did not improve. Furthermore, it also did not achieve its goal for increasing the supply for short stay off-street parking [1]. In order for the levy to be effective in achieving the goals stated, all drivers that require parking should have to face the costs in proportion to their usage. This means that this car park tax needs to tax appropriately on all users that need the resource instead of focusing on just subsets of drivers in the city. This internalizes the negative externalities, for example congestion costs, by targeting drivers in proportion to the costs that are imposed on other users of the road. Then this will be more effective in changing behaviours of drivers in response to the levy as they all now have to face a proportion of the costs, and some will decide to avoid peak hours when operators charge higher prices, opt for transit or other means of transportation.

By not charging to the proportional amount of congestion caused by drivers, the motivation to look for alternatives is weak because those who are charged are most likely the ones able to afford parking in the first place. In a sense, demand for parking is pretty inelastic because taxing those who drive to work in downtown will need a large increase before they switch permanently to transit since driving to work in downtown are mostly the wealthier ones to begin with. Thus, the levy only causes a slight response on the demand for parking and not very effective in stimulating them to turn to other modes of transportation.

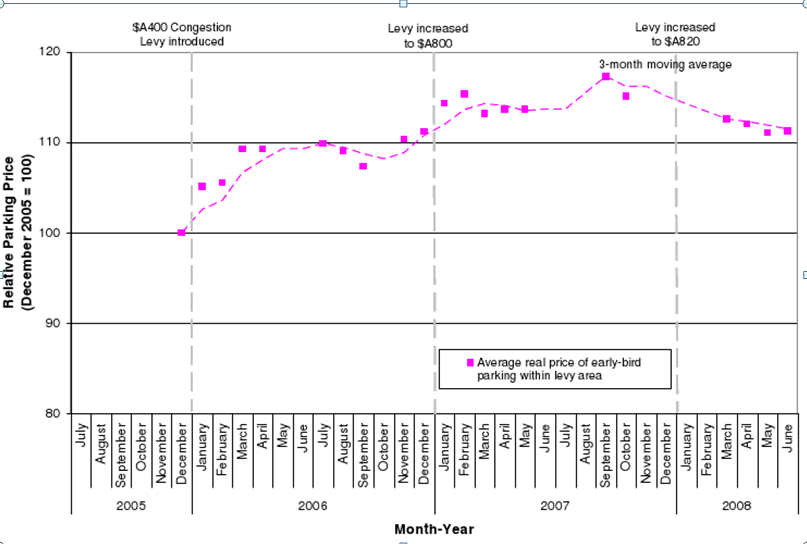

Very obviously, the distributional effects of this levy are geared towards the rich people who can afford to drive and park all-day in downtown. The selective nature does not treat all those who create congestion equally because it has no direct penalties for those drivers who cause congestion by driving and not requiring parking. More directly, the levy does not apply to short stay off-street parking, and is only charged at an annual flat rate. However, this further encourage commercial parking operators to treat their customers differently such as by slightly increasing early-bird parking charges while significantly increasing short stay drivers due to the levy[2]. For example, when the levy was implemented in 2006, early-bird parking increased within the first few months and again increased in the beginning of 2007 when the levy was raised from $400 to $800 in 2007. However, as seen in Figure 1, the early-birds were not charged by all operators for the effects of the levy because the parking price increased by 17% from Dec. 2005 to Sept. 2007 when the levy was $800 in year 2008, and this was actually a 28% preimum on the price that was in December 2005. Since these were done in real terms, this means that the parking rate increased by just a mere 11%.

Figure 1. Changes in real early-bird parking charges due to levy imposed. (Source: Transport Research Forum, 2011)[2]

In contrast, the poor are not affected as significantly by this levy if they are not driving and parking in downtown. In fact, since the revenue generated from this levy is proposed to be used towards improving public transit, then the poor would indirectly benefit somewhat from this levy in the long-run. This improvement in transit would also mean that the rich who are targeted by this levy are indirectly supporting the cost for improving public transit. As congestion has not been found to have decreased significantly from this levy since the cost is not high enough to reduce their demand for parking, the poor can be viewed as benefiting from this levy while the rich are penalized for driving to work.

Even though this levy generates a solid and steady flow of revenue, the method is selective and achieving those stated goals are not practical with this policy. Instead of reducing congestion costs, they are shifting them to the wealthier counterparts of the city and focussing on raising revenue. Congestion is due to different traffic and times, as well as types of vehicles on the road, but this levy is pin-pointing into a small portion of road users instead of taxing everyone proportionally.

Furthermore, since the levy is applicable to the owner of parking spaces, different operators will respond differently to the levy. Some may pass more of the costs onto their customers while others choose to absorb more themselves, and on it goes. Thus, this is also inefficient in discouraging drivers to drive into neither downtown nor changing their transportation behaviours. However, since the revenue generated from this levy goes toward improving public transit, then perhaps it can improve congestion indirectly, but this also depends on how substitutable transit and car driving is. In this case here, since demand for parking in Melbourne is already quite inelastic, then transit is not very substitutable unless revenue improves it in the long-run.

[1] https://www.propertyoz.com.au/wa/library/05%20AE%20VIC%20Melbourne%20Car%20Parking%20Levy.pdf

http://www.eng.monash.edu.au/news/shownews.php?nid=43&year=2012

http://www.sro.vic.gov.au/SRO/sronav.nsf/childdocs/-3A87315B22BC23FFCA2575A100441F59-EFC160ABBE873990CA2575B70020FC3B-7A9067647FE241FBCA2575D8007DF289?open