One element that stood out for me from Vertov’s Man With A Movie Camera was the sheer creativity he demonstrates with the camera. The camera isn’t just a window into the world of film but a character itself; Vertov uses it in different ways, not only to communicate literary meaning but also to show what was possible in cinema at the time. Although I don’t know that much about precise film terminology, I’ll try to point out what interested me after looking at this film more closely.

(I apologize for the 2000+ word count, but this is in lieu of me forgetting what I wanted to say about this film)

1. Split Screen

Vertov uses split screen fairly often throughout his film; usually the individual parts are thematically related, but are not always shot at the same angle/distance. Of particular interest is that fact that many of the split screen effects are horizontal, rather than vertical, which is the type of split screen mainly used nowadays. This shot, in which the cameraman is setting up his camera, presents a good example of how Vertov uses this technique to create a complex composite image:

Here, Vertov presents two different angles and sizes that contend for the viewer’s attention. The screen is not evenly divided, leaving the bottom image, the close-up of the camera, to act almost as a platform for the top image, which contains a long shot of the cameraman setting the camera on the tripod, as the camera in the bottom image and the hill in the top image line up.

Another example would be this triple split screen:

In this shot, Vertov stacks three similar shots together to create the illusion of a large crowd; the higher up on the screen, the smaller the people get, simulating how distant objects appear smaller and how the . What fascinates me is how

Although this may have seemed fresh and exciting at Vertov’s time, split screen has now become prevalent in television and some later films, making this a definite harbinger for things to come.

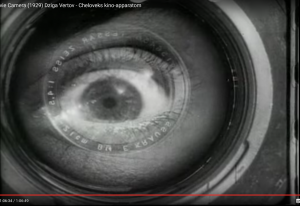

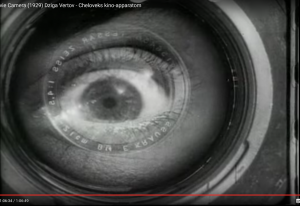

2. Multiple exposure

I first learned about this technique when I was researching this film a bit more, but from watching the film itself, it is plainly obvious that Vertov is fond of the effect. He superimposes multiple images for sometimes bizarre effects, such placing the camera-man inside a glass (~55:19), or combining multiple images after a series of increasing quick cuts, which begin still decipherable by the human eye and speed up into a flicker of shots that last barely more than a frame before merging together, as seen below:

And the image of an eye superimposed into the lens of the camera is rich in symbolic and thematic meaning, characterizing the camera as a powerful, all-seeing eye. Through this technique, Vertov creates images the human eye can only imagine but never create, demonstrating the camera (though somewhat deconstructing his Kino-eye theory) as an imaginative/evocative as well as realistic apparatus.

3. Off-angle shots/Dutch angle

I was surprised to see how frequently Vertov uses this technique, but what stood out to me the most is how he uses a changing camera angle to achieve several emotional effects. During the scene where the cameraman is filming an upcoming train, there is a series of shots in which the camera rapidly tilts back and forth, which amplifies the tension and disorients the viewer, simulating the shock of the event. Additionally, near the end, there is a brief sequence (~ 56:00) where the camera also swerves back and forth, producing a sense of vertigo for the viewer and replicating how humans under duress tend to view things, unfocused and shaky.

Finally, there is this shot, which is undoubtedly one of the most memorable in the film.

The two halves of the shot fold into each other, the composite symmetrical image of the city appears to collapse in a brilliant illusion. What we are seeing is entirely an editing room creation, the results of extensive post production; in a sense, this is the camera, or the Kino-eye playing magic tricks on the audience, showing just how superior it is to the human eye .

4. Tracking shots and other camera movement

This is a film in which the camera is truly alive. It captures moving vehicles, keeping pace alongside them, following the action instead of letting it slip by the frame. There are multiple segments in which the cameraman rides alongside different vehicles, and even on a merry go round, and shots where the cameraman is seen standing in a car filming another car to acquire these shots.

Some other examples of techniques that I find commonly in modern films, but not at all in the other two silent films for this week are the hand-held, point of view style of filming in ~17:25-17:35, where the unseen cameraman follows the on-screen cameraman, which definitely reminds me of how documentaries and other genres of films are made nowadays, as well as a unique 360 degree camera rotation in ~41;54-59 (commonly used for dramatic effect in modern cinema, as far as I know), and the panning between two women sitting near each other to simulate the effect of a back and forth conversation in ~35:15-35:21, somewhat as a precursor to the many techniques used nowadays to add visual interest to a generally dull conversation between two characters.

In that sense, this advances the paradigm that the camera’s movement is as important as the movement of the objects and people within the scene. Unlike something like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which uses fixed sets without much depth or sense of space, the entire city is Vertov’s set, and he can explore it, manipulate it, experiment with different angles and distances, so much that the sense of claustrophobia from the close-ups of machinery and the sense of grandeur and scale from long-shots and expansive tracking shots are both equally prevalent.

5. Slow-motion

Even though Vertov does apply the opposite effect, speeding up some of the scenes (for example, ~43:44, where my butts moving in the sky above the bridge imply a long time has passed, an effect commonly used nowadays), the use of slow motion in the athletics scene is particularly effective in conveying the magnitude and emotions of the events happening before our eyes. The high-jumper’s feat is made all the more impressive when we see just how he clears the bar. It is quite obvious how slow motion has impacted modern cinema and filming; we see it everywhere, and it is surprising how Vertov, in the 1920s, uses it for essentially the same purpose as we do nowadays, to punctuate and add emphasis to a scene. It literally stretches (or compresses) time, another clever effect that a camera possesses in contrast to the fixed speed of the human eye.

6. Erotic and graphic material

It is all too easy to assume that early black and white silent films were rather limited in what they were allowed to show on screen. However, Vertov presents the audience with some jarring material, in particular the childbirth scene, cross-cut with scenes of a funeral, and quite briefly depicts the newborn child, with its umbilical cord, being pulled out of the uterus. I did not expect such a scene, but it certainty adheres to Vertov’s idea of an objective cinema, free of so-called moral censors.

Additionally, the beach scene contains a few examples of nudity as women rub mud over their bodies. There isn’t a lot of emphasis placed on the nudity, indicating that this wasn’t a big deal at that time.

Despite this, Vertov on several occasions allows his camera to linger on certain suggestive scenes that even today would probably be frowned upon by major production studios. The woman at the beginning of the film is filmed putting on her stocking, along with her , which is accompanied by a close-up of her back. A shot near the end of the film which depicts a young woman dancing is shot from below the subject, bringing emphasis to her legs and the revealing nature of her dress.

But what strikes me as unorthodox is the focus put on physically active women, in comparison to the maternal ideals of the past century. Women are seen participating in athletics and team sports, pulling weights and shooting rifles, all typical masculine activities. Women are also seen working in factories, or as typists or radio operators. This all helps contributes to the idea that this is a Marxist-Leninist film, in that it glorifies the working female proletariat rather than demonize her.

7. Stop-motion animation

Vertov dedicates nearly a minute to a scene (~59:39-1:00:32) in which the camera and its stand move on its on accord, seemingly through magic, but practically through stop-motion animation, which is where models are moved by small increments and filmed to achieve the illusion of movement. This is another way in which the camera plays tricks on the audience’s eyes; through film editing, objects can be made to move without human interference by simply removing human interaction from the film recording itself. In the context of the film, this also demonstrates the camera as a character by itself, capable of moving around and setting up shots by itself.

8. Cross-cutting

Vertov makes excellent use of cross-cutting, or shifting between multiple scenes, presumably happening at the same time, in this film to create a sense of anticipation for upcoming shots, and this enhances the lively, rhythmic nature of the film and its editing. Cross-cutting is used in both thematic contexts, to juxtapose scenes, or simply to build tension. Near the beginning of the film (~14:43-15:18), shots of people interacting machines is crosscut with the cameraman climbing a tall tower; there is a sense of progression and anxiety with the cameraman that is created by splicing individual sections of his ascent with scenes of people and machinery. The juxtaposition of rote activity with something more exciting is something that I believe is remarkably effective for enhancing tension and providing momentum, and I have seen it many times in more modern films. An example of thematic cross-cutting is where Vertov presents a variety of shots where people are washing objects in the city or themselves (~11:24-11:42). The idea of water connects the scenes together but also links the people and the city together (as stated in lecture), presenting a fully united communist state. Also, the cross-cutting between childbirth and a funeral generates entirely unusual emotions. A funeral is solemn and mournful, yet childbirth is intense but eventually joyful. These aspects contrast each other in every way, essentially cancelling each other out to relieve the instinctual emotions present when viewing such scenes.

Another example of cross-cutting is where Vertov inserts shots of the audience during the athletics scene and also during the magic trick scene (~50:28-51:04). This emphasizes the gravity of the actions occurring and the sheer amount of scrutiny being placed on it, and this is almost ubiquitous in editing nowadays I believe. Cutting to different people and their reactions to the ongoing scene acts as a measuring stick for both the character in the film (if they are recurring), and the audience as well, and a way of providing forward momentum by staggering the main flow of events.

9. Variety of shot compositions

The last technique I noticed was how Vertov contrasts different types of shot compositions, ranging from symmetrical and orderly images to the swiftly moving scenes of machinery turning and vehicles moving along the road. One example I found of a symmetrical, tightly composed shot, was this image of a car, which is perfectly square to the camera, the grille at the front allowing perpendicular lines to run across the screen. It is almost too perfect, uncanny in a way, yet after this the audience sees only scenes of moving cars.

Additionally, I find the scene involving the merry-go-round (~53:42) to be very skillfully made. It places the merry-go-round and the people riding on it into focus and the spectators out of focus, creating both foreground and background elements. This is an essential part of modern cinema from what I’ve heard, the skill to manipulate focus, who or what to focus on, whether a deep or shallow focus is necessary.

Finally, I noticed that Vertov films from different heights, often from rooftops, or other higher elevation, and also from different angles, tilting the camera upward to gaze at objects from a much different perspective. These angles, in my opinion, help lend a more varied feel to the film which made it much less sleep-inducing than Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, at least in my opinion.