Hi! My name is Max, and I’m a Literature major / History minor entering into the fourth year of my undergrad (of five, alas). This is my blog for English 470, a class which will explore Canadian Literature through a lens of postcolonial criticism, focusing on the influence of European and Aboriginal traditions.

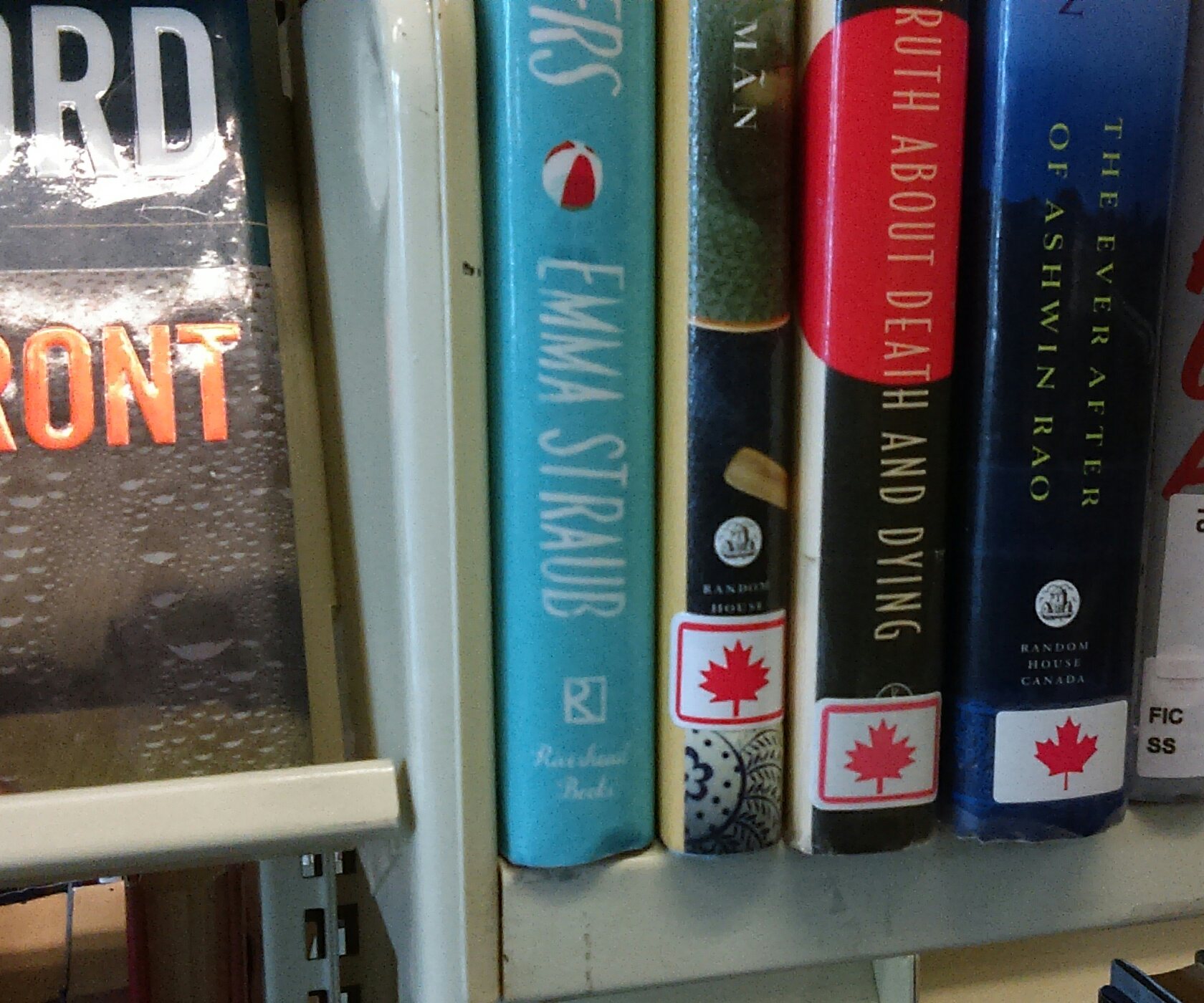

Despite living in Vancouver for all of my 21 years, I’m still nebulous about what CanLit actually is. I’ve worked at Vancouver Public Library for a number of years and find myself surrounded by CanLit on a daily basis. It’s easy to tell because we announce a book’s Canadian authorship by sticking a maple leaf on its spine:

One book that always catches my attention is The Sisters Brothers by Patrick DeWitt. I haven’t read it personally, but by most accounts it’s a fine book. It was awarded the Governor General’s Award and the Rogers Writer’s Trust Prize for being the best example of CanLit in 2011. It’s a Western set in California, and its author lives in Portland.

I think this is a problem, although my issue is not whether or not it is a good novel, but whether or not it is a good Canadian novel. It has no interest in Canadian heritage and does not engage with the country’s history; it is being celebrated simply because its author was born on Vancouver Island.

Writing this blog, I’ve realized most of the Canadian Literature I’ve studied could be more properly called “literature by Canadians.” Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaajte, Yann Martel, and yes, Patrick DeWitt – the subjects of their stories are varied, and while some of them may be set in Canada, the setting does little to inform the tales.

My argument is not that these books don’t have value – it is just that they do not distinguish themselves as Canadian literature. Including these authors under the Canadian Literature umbrella makes it a category rather than a genre, and branding their books with maple-leaf stickers seems to be little more than an empty nationalistic gesture. This is especially a problem as “literature by Canadians” seems to be more popular and generally win more awards than books that engage with Canadian heritage and traditions: Paul Yee’s stories of Chinese immigrants arriving in Canada, Joseph Boyden’s use of Aboriginal myth, The Hockey Sweater.

I want to stress that I am not criticizing any of these authors for writing what they write – my concern is with the way our culture classifies and celebrates CanLit. By presenting “CanLit” as simply literature with a different place of origin I feel like we risk homogenizing Canadian literature, and as a result losing touch with the roots and history of our nation. Considering the current political climate, and the continued mistreatment of Aboriginal people by our government, I feel like lack of representation could be a real issue.

Since I’m already well over my word count here’s the tl;dr version – I find the approach this course is taking incredibly refreshing and I can’t wait to get started!

Hi there,

Great points about the content about Canadian literature, and what really defines a novel as a “Canadian” novel. I especially enjoyed the image of people slapping maple leaf stickers on the backs of books written by Canadians.

What do you think makes literature, Canadian literature then? Very vague question, I understand, but perhaps an example novel or book, that gives insight to the requirements would be solid answer for me. Do you think creating a checklist of requirements would be helpful to classifying what makes a “Canadian” novel a “Canadian” novel? Also do you think that someone born outside of Canada, could write a novel about Canadian heritage and Canadian history, and not be classified as a “Canadian” novel?

I share Jeff’s question about what exactly does define Canadian literature. Separating “writers of Canadian Literature” with “writers of literature who write in Canada” is a very problematic distinction that in a way subverts the very identity of Canadian literature. For if we, as Jeff suggests we might, create a checklist of requirements defining Canadian literature, and if that checklist does not include the requirement of being a writer who writes in Canada, then it becomes possible for a writer writing in any part of the world to produce so-called Canadian literature. Would it really be Canadian then? We could of course include the requirement of being a writer writing in Canada, but that would create an even more problematic distinction where we ultimately judge a text as Canadian literature not by its content but by where the writer writes.

I think that in the end, the best way to classify a nation’s literature is to recognize all literature produced in that nation. Similarities will occur and checklist-suitable elements will emerge, but that does not justify excluding literature that does not fit the trend: those can still be Canadian books, just not books like other Canadian books.

I really enjoyed reading your blog, and I was quite interested in your question of what makes a book Canadian. I hadn’t realized that a book like The Sisters Brothers could win such prominent awards simply because the author was born here. As a writer who is now a Canadian citizen but was born and lived for 17 years in the US, it makes me wonder what would be required for my own work to be considered Canadian – I’m assuming it wouldn’t count if I lived in Portland!

I also found myself thinking about your suggestion that Canadian literature should have content that is in some way Canadian, and the way British and American literature fits into this. Those literary traditions often feel more established (probably as a result of which works are given attention) and yet books that are labeled British or American Lit often seem less aware of their national identity and don’t necessarily have a lot of content that’s specifically about their setting. Maybe it has something to do with how literature in these larger countries are considered the “default” and therefore it doesn’t need to be as self-conscious about it?

I would love to hear your thoughts on this!

Hi Max – a great introduction, your points are well-taken, and I do indeed think you are going to enjoy this course of studies: Welcome! I am looking forward to our work together, and thanks for some great hyperlinks. Enjoy. Erika

hey Max, I thought I would comment because I have similar questions regarding the forging of some kind of “national canon.” What is the value of these types of lines in the sand, these generic or categorical distinctions? If I’ve taken anything away from my time in post-secondary, it is that these boundaries are always fluid. My mother has an MA in CanLit and was surprised to see that she knew few of the names on the syllabus; so, evidently, the idea of “Canadian identity” reflected in literature has changed over the past few decades and is likely to change again in the time between my writing and posting this.

I also think you make a good observation regarding the marketability of Canadian content. Using national symbols in some vague attempt to spark patriotic consumerism does seem to be pretty shallow. Anyhow, solid post, and I hope we come out of this thing with a more nuanced idea of what CanLit is, or at least some way to approach it.

🙂