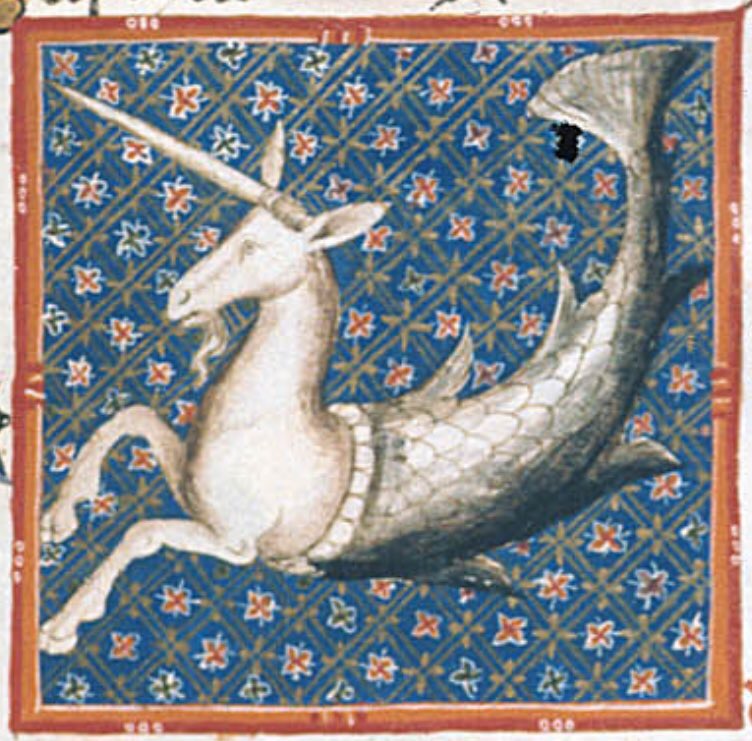

Matfré Ermengaud, Breviari d’Amor (Occitan verse version, early 14th c.), British Library Royal MS 19 C I f. 11v. See also: British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog, “The language of love (and poetry and history,” 23 June 2017.

TUESDAY

Introduction and overview of the course and how it came to be (see also: prologue and a preamble)

Some key areas of current work in Medieval Studies, via MLA 2018:

- environmental humanities and ecocriticism

- a global Medieval, and globalising Medieval Studies

- a whole multisensory Medieval: especially integrating sound studies and the idea of soundscapes

- soundscapes, music, architecture and a whole integrated environment (you can see how environmentalist ideas stay central, and humans as part of that environment as a whole, as creative but also social beings)

“What is a marvel?”

Some keywords from you! In no particular order…

- mythology

- monsters

- gods

- heroes

- the subjective and relative nature of “a marvel”: ex. the printing press (to someone who has never met one before, inc. here and now`0

- technology (ex. digital humanities ex. interactive Bosch online)

- hybrids

- places, ex. Atlantis

- maps, ex. with Jerusalem as the centre, orientation to the East not the North, proto-/pre-maps not necessarily for the same purpose as maps today; not representational but relational, and including story-telling and cues for it (“here be monsters”)

- spiritual places

- weird monsters in the margins of maps, and ideas of marginality as well as of what is definitely “beyond”

- bestiaries

- Harry Potter

- The Cool (marvellous, wonderful, wondrous, awesome, etc.) and The Unusual; the extraordinary as that which is “extra” (beyond, above) the ordinary

- Egypt (and other Other Worlds) inc. deities and other beings with animal heads, ex. Anubis and the Sphinx

- dragons, unicorns, and the symbolism behind and around them (ex. the unicorn and Christ)

- Viking mythology, ex. the Tree of Life (and how that mixes with other symbolisms, and the phenomenon of remixing and translating symbolic and cultural systems, ex. Christianity and other religions)

- witches

- military history (see also: heroes), crusades, Charlemagne, the Paladins

- Icelandic sagas

- visions

- miracles

- hagiography (saints’ lives)

- how to categorize “the marvellous”

THURSDAY

PROLOGUES

From the beginning, to a first miracle / magical or supernatural act of creation, to a world of wonders…

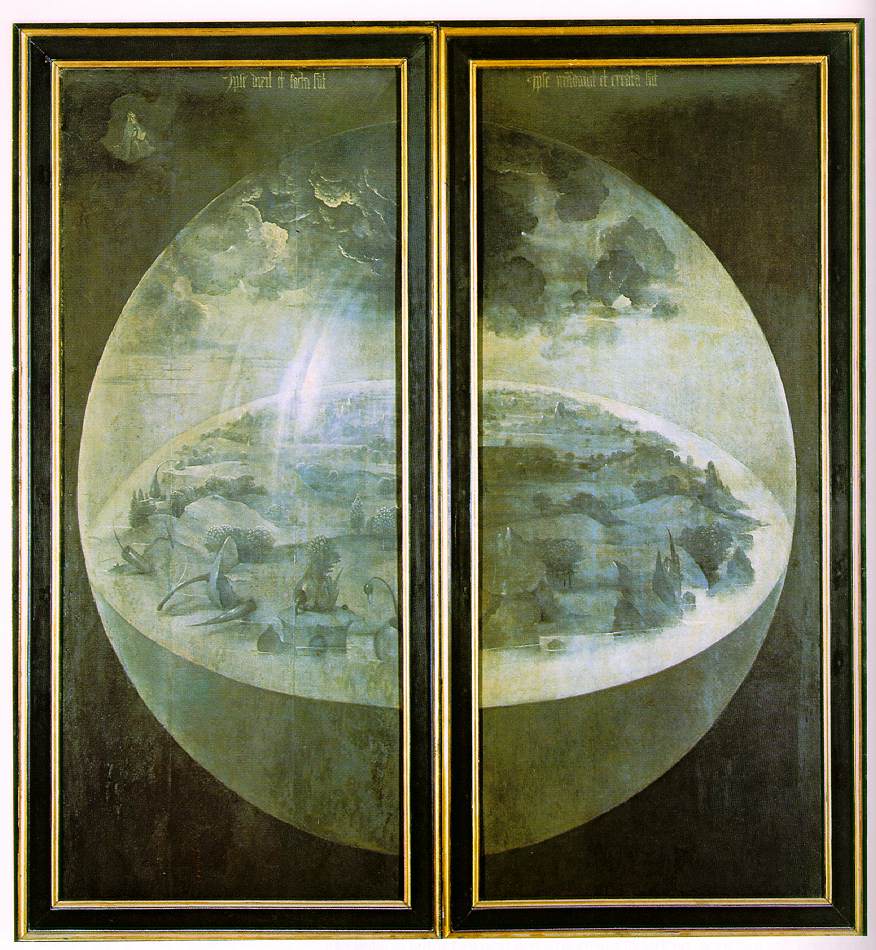

(Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510): the triptych closed… and then opened)

The “marvels” of knowledge, a book, and how you organise works that are collections of narratives, or collections of items (with their stories, which are an essential part of them). Starting with what comes before the “logos” of sense and reason and reasoning: the pro-logue.

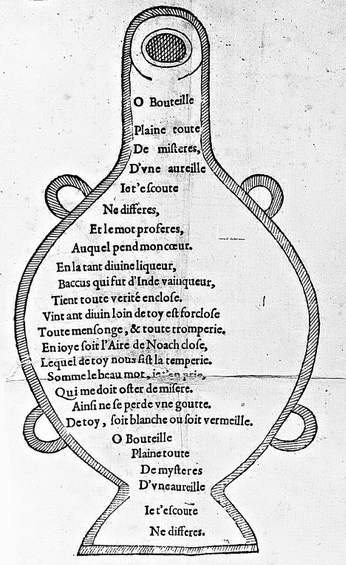

1. Rabelais, paratextual and prefatory materials (books 1-3)

All 3 books: introduction, synopsis, vision of what is to come; cornucopia of treasure that await, lists of marvellous things: from hybrids such as flying goats, to titles of chapters (and other books), to precious substances.

The role of paratextual material as part o a text: book cover, contents-page, dedicatory poems, prefaces, preambles, prologues … an incitement and promise of wonders to come …

GARGANTUA:

Silenus boxes and the vertu merveilleuse inside (p. 206, “miraculous virtue”): duller or uglier (or frivolous, superficially silly) exterior and promise of what lies within, drugs and medicine.

Marvel 1: that magic of opening the box.

2: what is inside and (like the outside and its opening up) the potential for its effects.

3: what’s inside crosses time and space, brings together worlds of knowledge (see classical examples), educational and healing power, and joy.

4: the contents themselves are marvellous (translated variously as miraculous and magical, also extra-ordinary, other-worldly) and have a power to transform. An elixir to drink, which we’ll see again in book 3. See also Pantagruel, end of prologue.

5: celestial, superhuman, miraculous: understanding and laughter, marvels that are distinctly human; see also TO THE READER and the opening poem at the start of BOOK 3

PANTAGRUEL:

opening dizain, laughter (at humans here) again.

Another marvel: the technology of printing

BOOK 3

Printing and the printing privilège (permission, authorization) in perpetuity, past and present and future.

Elaboration of the joys of drinking; embedded example and Diogenes and his barrel; the same from which we’re drinking here; also the same (miracles again) of the wedding at Cana (note also how we bring together Classical and Biblical exempla).

BRUNETTO LATINI

Another bookish example of organising knowledge and explaining its rationale and purpose (see also the Breviari d’Amor, some of whose illuminations feature at the start and end of this present post): Li Livres dou Tresor (“book of treasure”); Brunetto Latini portal, British Library Yates Thompson MS 19, and its beginning.

MARIE DE FRANCE

Reading and the transformative power of education (inc moral). Marvellousness and another transformation: translation, rewriting, bringing to new audiences, preserving; as with Rabelais, you’re seeing a literary work serve as guide and bridge across time, space, and worlds; bringing you into other worlds and also bringing them into yours, keeping them alive. (More next week, on Tuesday…)

Other examples: Matfré Ermengaud, British Library manuscripts & blog post(s), compendia and encyclopaedias (Pliny, Isidore, Ptolemy’s Geographia: marvels can be extraordinary but also ordinary, all around us; plus the other world in or touching on our own, of its borders and margins; ex travel narrative, John Mandeville, Gerald of Wales; and universal histories and chronicles).

And a first unicorn: Matfré Ermengaud, Breviari d’Amor (Catalan prose version, late 14th c.), British Library Yates Thompson MS 31 f. 48r