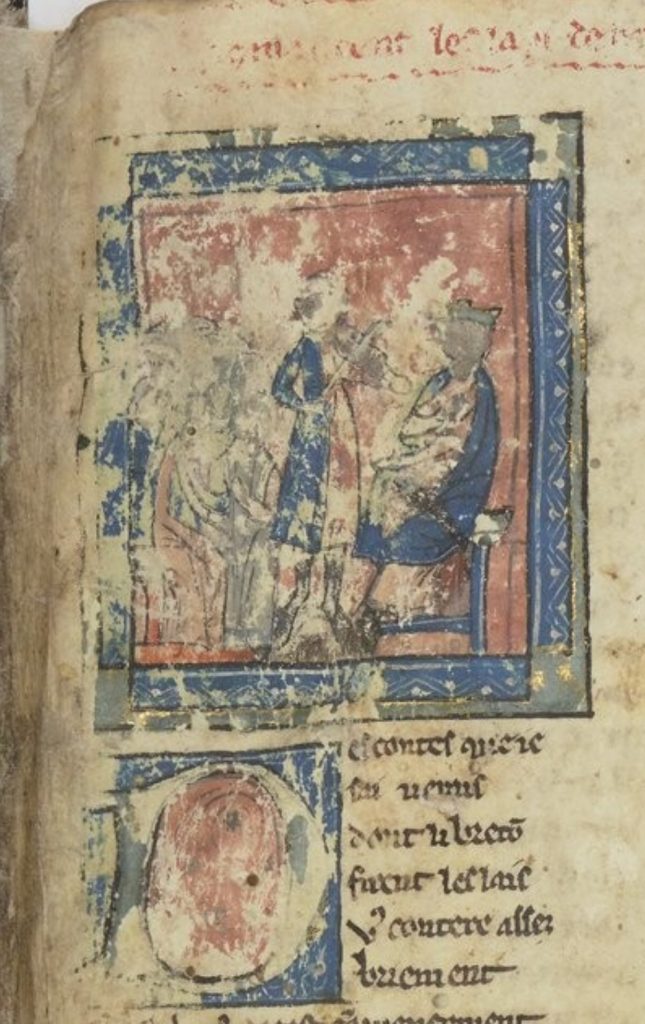

Performance notes… (BNF NAF 1104 f. 1r)

BESTIARIES, FABLES, METAMORPHOSES, AND MARIE DE FRANCE

TUESDAY

PROLOGUES (from last week)

Reading and the transformative power of education (inc moral). Marvellousness and another transformation: translation, rewriting, bringing to new audiences, preserving; as with Rabelais, you’re seeing a literary work serve as guide and bridge across time, space, and worlds; bringing you into other worlds and also bringing them into yours, keeping them alive.

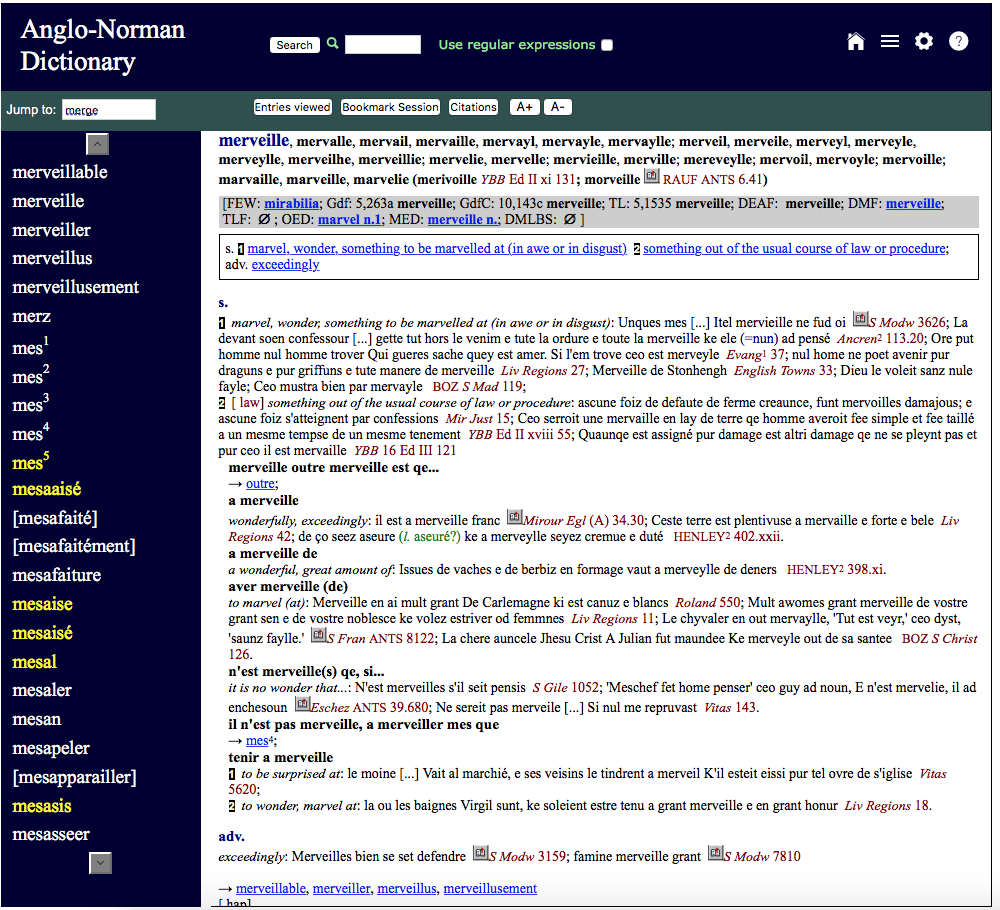

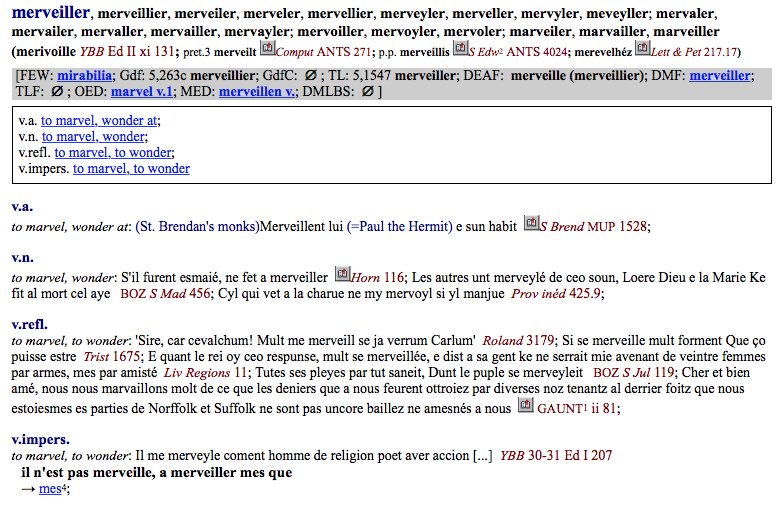

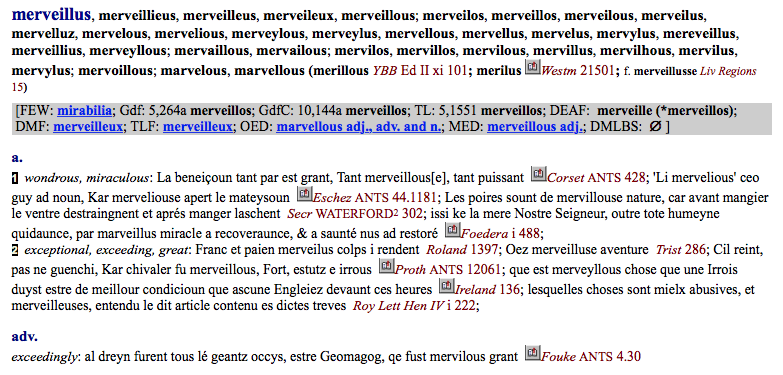

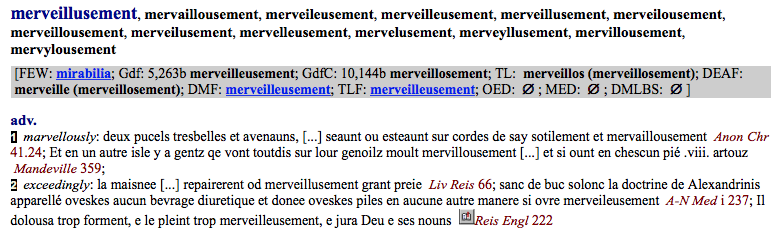

(more on this on Thursday) Anglo-Norman Dictionary: the “merveilleux” in Old French.

Marie de France’s Fables and Lais, the manuscripts and transmission history (inc. their teaching)

- the manuscripts, via the International Marie de France Society

- Lais: British Library (London, UK) Harley MS 978 (manuscript H) f. 139a-181a, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris, France) MS fr. 2168, fr. 24432, nouv. acqu. fr. 1104 (manuscript S) f. 1a-45d

- the Purgatory of St Patrick: pilgrimage, travel to the underworld (which is another Other World)

- late 12th century multilingual England, but with French as high-status cultural language (via Norman Conquest and Anglo-Norman aristocracy; at this stage of linguistic development, this is a form of Norman French; related to the current form used in the Channel Islands (still called the “Norman Islands” in French))

- context, background, environment: abbeys, convents, Benedictine nuns

- manuscripts: mainly mid to later 13th c., period of significant manuscript production and circulation; new techniques enabling more, faster, cheaper; includes a blossoming of encyclopaedic works: universal histories, books of all knowledge, collections, compilations, compendia, giant “song-books” (chansonniers, canzoniere: anthologies of (mostly lyric) poetry), miscellanies; some of which are made by or with women religious. May include herbals, natural history, medicine, magic. An earlier example: Herrad of Landsberg, Hortus deliciarum (another “Garden of Delights”); I also referred in passing to Trotula of Salerno.

- fables: version (“translation” in strict and broad senses) of Aesop’s Fables, one of many (popular text and material, also continuing to circulate orally and across political borders and cultures and languages at the same time)

- lays: short (compared to a tale (conte, “told story, telling”; related to account) or romance) verse narrative related to German Leich > Lied and Irish laid (song); retaining aspects of oral performance, probably also performed; one of several instances of the flow between oral and written, reading and listening, a confluence rather than simpler binary distinction

- material: retelling Breton lays; with connections to Breton (obviously), Cornish, Welsh, and Irish material

- movement across languages, and language change and cross-influence, and translation are also forms of metamorphosis, “changing shape” and—when going back and forth—“shape-shifting”; both in the narrow sense of translation (language A —> language B) and the wider one of transformation and refashioning (with subtractions, additions, amplifications, continuations, changes of place and costume and customs, cultural and contextual relocation … including dislocation into other worlds and non-worlds)

- warning: may contain skewed morals / lessons; or unexpected ones, or paradoxical, playful, satirical, imaginative / hypothetical / unrelated to the actual world; or none at all. This aspect may be enhanced by the lays’ irrealism, irreality, atemporality, other-worldliness

- introductions: Judith Shoaf, Wikipedia, International Marie de France Society > About Marie, About her World, About her Lais

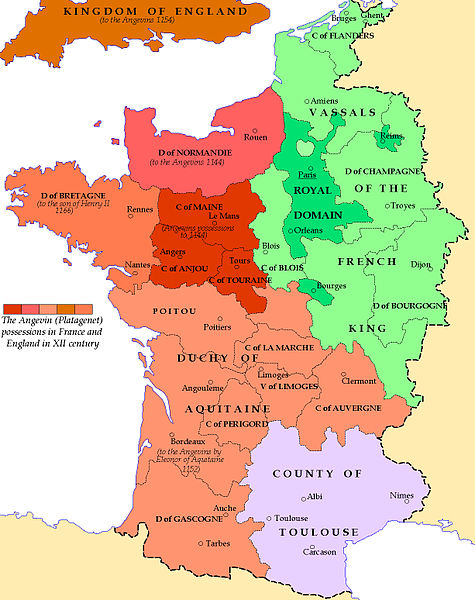

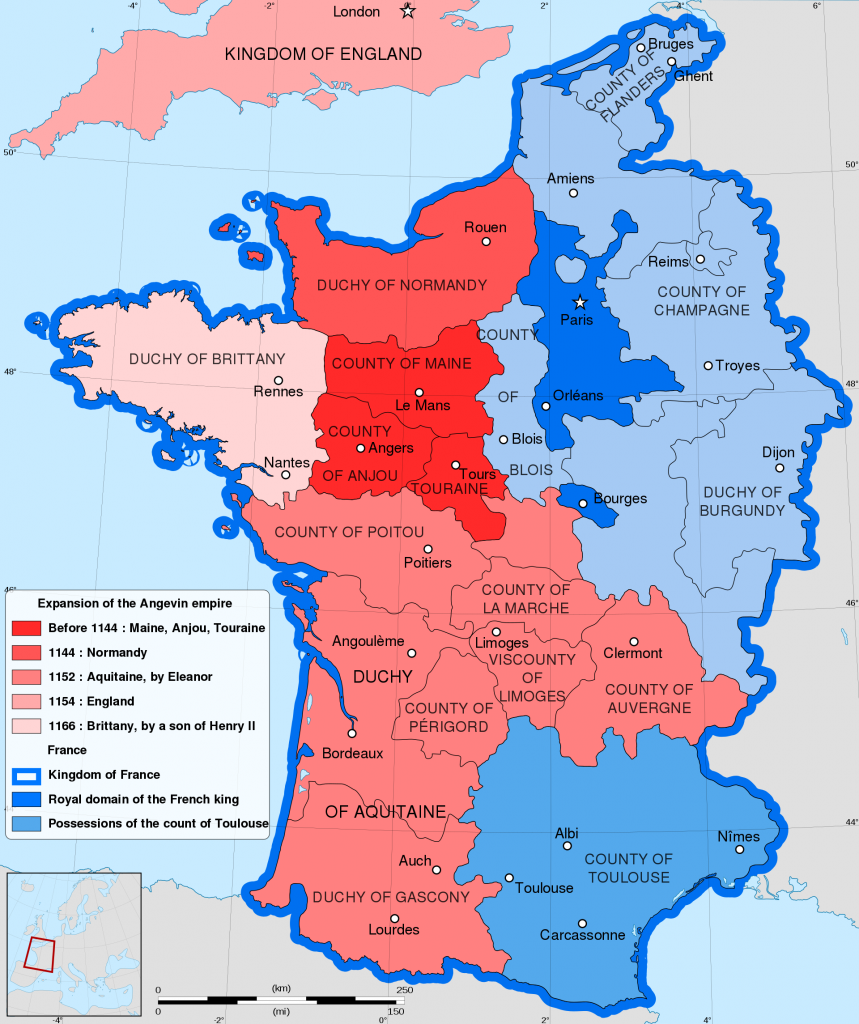

- maps below: adding a further reason for reference to certain places in the Lais (besides proximity; familiarity through trade, family, and other connections; fame; references as cues to associations with other literature and culture, ex. Arthurian): part of the same political entity (note that these maps are not uncontroversial, but they’re a useful basis; they’re also hyperlinked)

Languages in England towards the end of the 12th century:

- Latin & French (Anglo-Norman = what Norman French becomes once it has moved to England with the Norman invasion and conquest of 1066)

= official languages (government, administration, the exercise of power: royal court, courts of law, the church & its courts) and, in the 12th and 13th c., main languages of literary and scholarly / intellectual production - Middle English

= main working language; also used, increasingly, for literature from the 12th century onwards; becomes the dominant language for such work by the 14th century, helped in part by war with France (1337-1453) - Cornish (Brittonic Celtic language group)

- other forms of English closer to Old English / Anglo-Saxon persist and influence regional linguistic forms, becoming regional dialects later

Neighbouring languages:

- Welsh (Brittonic Celtic group)

Wales remains independent until 1282 (Norman conquest 1070s-90s, overturned 1130s-70s): kingdoms of Powys, Gwynedd, Deheubarth, Brycheiniog, Morgannwg, Gwent - Early / Older Scots & Gaelic (Goidelic Celtic language group)

Scotland remains independent until 1707 (when, by Act of Union, it and England will become a United Kingdom) but is close to England through most of the 12th & early 13th c. as, via marriage and inheritance, its rulers (and much of the attached aristocracy) are Anglo-Norman; this is why it appears on some maps of the “Angevin / Plantagenet Empire” (= Anglo-Norman) - Middle Irish (Goidelic Celtic group)

Ireland, at the time of Marie de France, has just been invaded and conquered (1167) and remains under English control until 1921

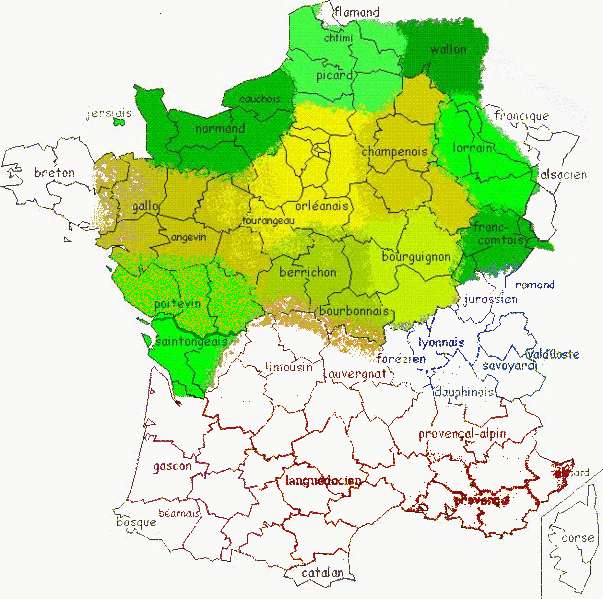

Languages in France towards the end of the 12th century:

- the “langues d’oïl” (Romance language group)

= languages in which the word for “yes” is oïl / oui (a linguistic distinction first appearing in Ramon Vidal de Besalú Razós de trobar (Catalan, writing in Occitan, c. 1210), later reused in Dante De Vulgari eloquentia(Italian, writing in Latin, c. 1302-05); the others are oc (see next item) and the Italian si)

forms of Old French, which will come closer together and become more standardised through the 13th c. (14th c., becoming Middle French); main written forms = those from the north of France (inc. Norman), being richer and thus producing more books - the “langues occitanes” (Romance group)

= languages in which the word for “yes” is oc

more usually called Old Occitan, used to be called Provençal (it is one of the languages): technically a koine, group of inter-comprehensible languages; major literary language in Europe at the time (ex. Troubadour poetry) - Catalan: also in the Romance group

- Breton: closely related to Cornish, also related to Welsh (Brittonic Celtic group)

- Basque: very different from all of the above and all European languages

THURSDAY

An exercise in spotting marvels and their mechanics: marvels that are beings and objects, marvellous moments, and moments of more or less magical metamorphosis. Your first course blog post will be about this, drawing on Thursday’s class.

BISCLAVRET: werewolves – compulsory MUST READ

Also, in order of less obvious, subtler marvellousness:

YONEC: bird-man magical lover

LANVAL: other-worldly lady lover, a variation on a classic question in amorous casuistry (I’ll bring examples from Occitan troubadour debate-poetry and the French Mélusine, see also Gawain’s lady)

CHEVREFOIL: short, Tristan + Yseult + marvellous stick

LAÜSTIC: nightingale as marvellous creature that transforms into marvellous object; also about reliquaries and books

(and EQUITAN—warning, bathing and murder—and other lays that have associations with the fabliau)

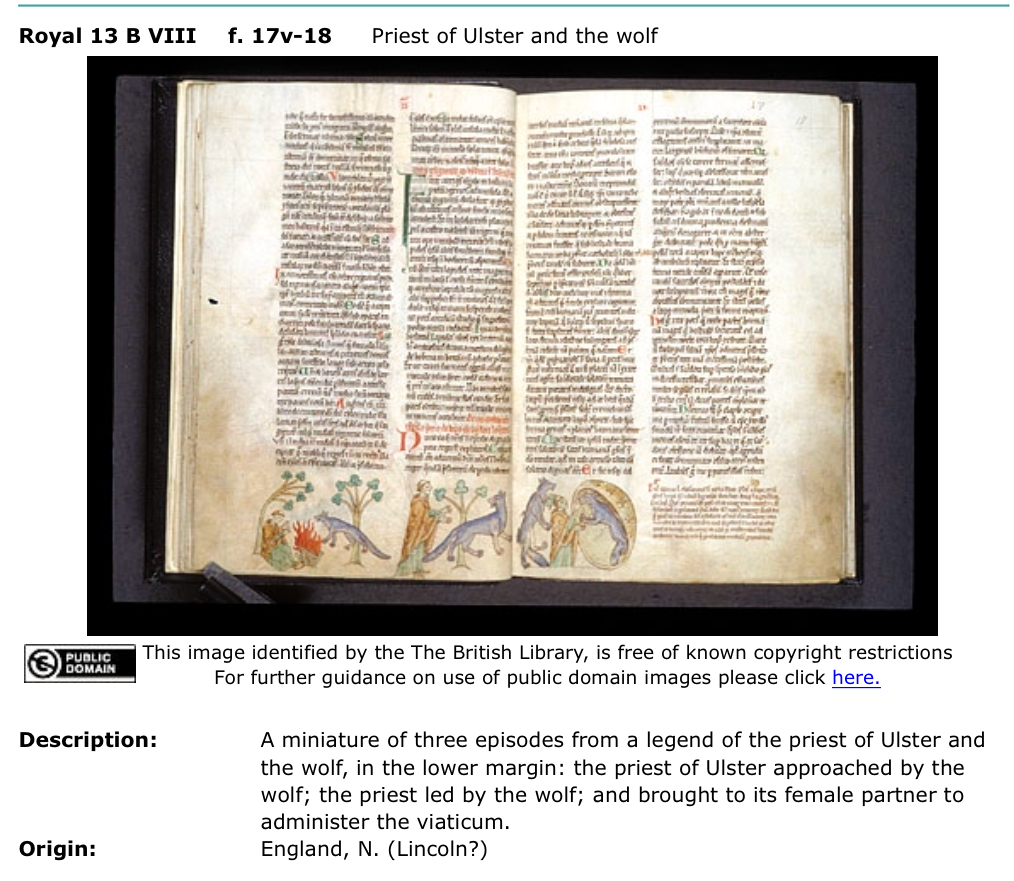

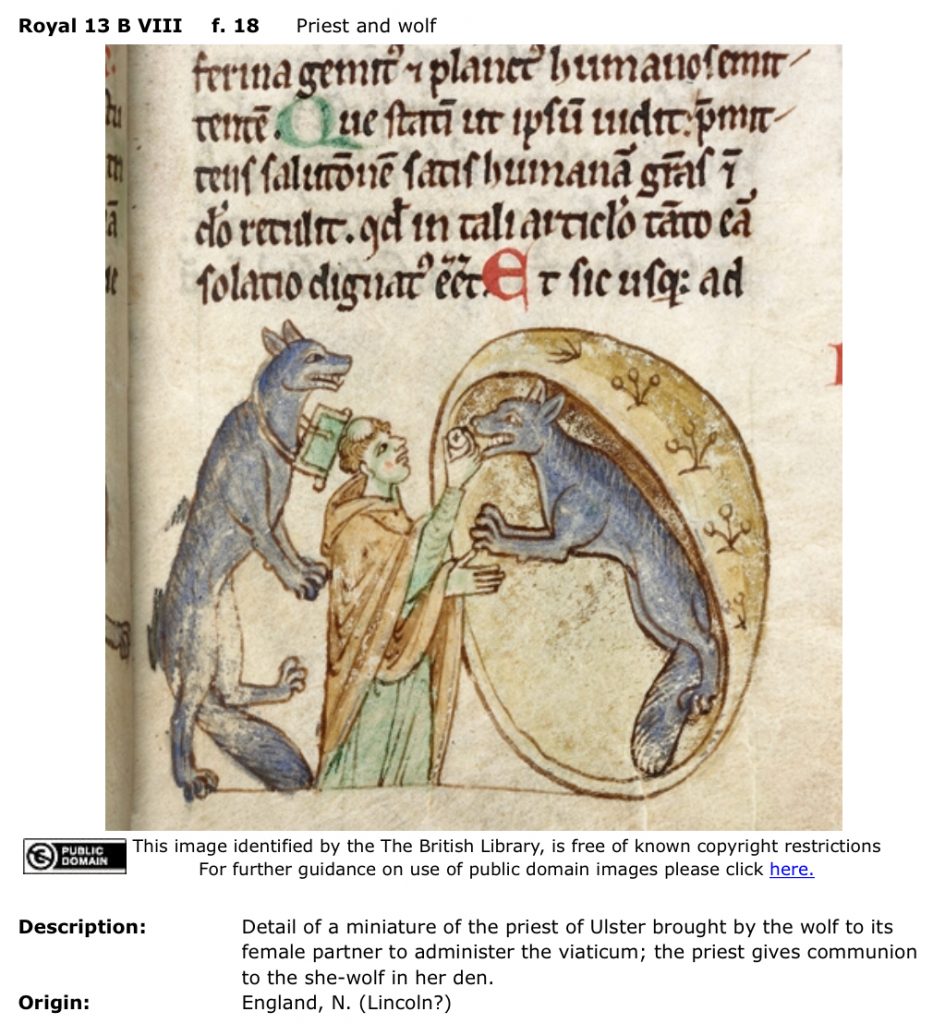

Overlapping or intersecting werewolves: Gerald of Wales who, like any of the proposed candidates to be identified as Marie de France, is also active in the late 12th c., in the same royal/religious high-status milieu and Benedictine monastic & manuscript-producing connections: Geography of Ireland, the werewolves of Ossory. British Library Royal MS 13 B VIII: