“In many ways, home is an image for the power of stories. With both, we need to live in them if they are to take hold, and we need to stand back from them if we are to understand their power. But we do need them; when we don’t have them, we become filled with a deep sorrow. That’s if we’re lucky. If we’re unlucky, we go mad.”

Chamberlain, If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?

I work at the UBC Learning Exchange in the DTES, in the Drop-In, a safe space for DTES residents to meet people, drink coffee, play cards, and use the computer. While the Learning Exchange’s programming focuses on community engagement and community-based experiential learning, the Drop-In is a place where most people come because they know it will be safe, warm, and welcoming. Many of our patrons are homeless or nearly homeless. Others are living in poor conditions — SROs, poorly managed BC Housing buildings, bouncing from shelter to shelter. Some are just residents of the DTES, a community in flux, looking for a stable place to get to know people in their community.

Many of the regular patrons who visit the Drop-In are Indigenous men and women who live in the area. Aboriginal peoples are overrepresented in the homeless population of Vancouver, making up for over a third of the homeless population while only representing 2% of the entire population in Metro Vancouver (Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee, ii). Over my last month working at the Learning Exchange, I’ve gotten to know many of the regulars pretty well, and some of them have been generous enough to share their stories with me. Without getting into details, most stories I hear have to do with Aboriginal people being taken advantage of in their own homes, being displaced, being disrespected, being told that they don’t belong in a city that is rightfully their home.

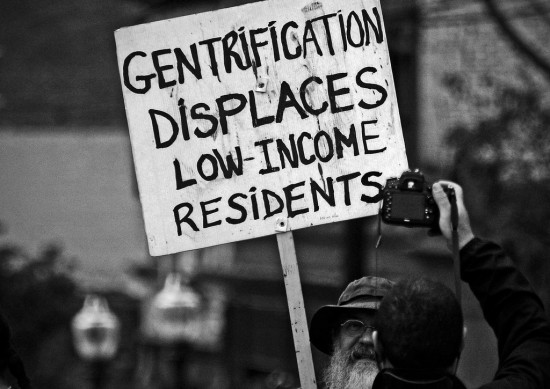

This is where home gets tricky. Chamberlain says, “home may be in another time and place, and yet it holds us in its power here and now.” This is the case with many Indigenous people living in Vancouver, in the Unceded Coast Salish Territories. Home doesn’t exist here anymore. Since contact, white settlers have been taking things away from the Indigenous people. Language and land, two powerful aspects of any culture, were stolen from the Aboriginal people. Today, things are still being taken away. Entire city blocks are being gentrified to be more appealing to white middle class Canadians, who are colonizing the DTES by destroying the area because they think it’s their right to do so.

The other aspect of the Learning Exchange is the English Conversation Program, a volunteer-run program that supports English learners by giving them a space to practice their language skills together. Most of the learners are Chinese seniors, many are low-income, living in Chinatown.

Just like the rest of the DTES, Chinatown is another rapidly changing area in Vancouver. Places like Matchstick Coffee, Bestie, Mamie Taylor’s, Nelson the Seagull have been weaseling their way into Chinatown and the DTES for years, getting a new kind of crowd involved in the neighbourhood.

Will these newcomers to the Downtown Eastside continue to use their comparative wealth as a tool of acquisition, compelling those they judge surplus to leave? At the moment, it looks that way. But the current drivers of gentrification must know that they’re small fry compared to the corporations that will follow, using their corporate power and wealth to displace them. And when all that is left is a Disney-fied strip mall of Starbucks, 7-Elevens and Money Marts, will the owners of Cuchillo and PiDGiN be proud to say that they helped make it all possible?

I was chatting with my coworker outside of work the other day, standing on the corner of Main and Keefer, and we couldn’t help but notice the strange mix of people in the neighbourhood. There was a group of young, hip 20-somethings with sour looks on their faces skateboarding past a Chinese senior couple, shuffling slowly along the sidewalk. There were men is suits stepping out of the new Starbucks across the street (which I’ll mention in a minute), and a bustling Chinese market right next to where we stood. These images alone indicate to me that the town is changing.

The Keefer Block is a new condo development on Main and Keefer, and is a testament to the changes in the neighbourhood. The development’s website boasts the boutique apartments, saying that buying one of their being a part of Vancouver’s “vibrant cultural identity,” but that are really displacing people within that culture. You likely know of this building because it’s home to the first standalone Starbucks in Chinatown. If you didn’t believe Chinatown was dying before, this must convince you.

Artist Rendering of the Keefer Block. Very few features of Chinatown are represented in this photo — you’d almost think this was Yaletown.

Just like with the Indigenous people, Chinese peoples’ land is being taken away, their language is being stolen (signs are popping up in English only, making many businesses inaccessible to non-English speakers), and they are being displaced — priced out of their own neighbourhoods because yuppies want to live in a cool, hip, edgy neighbourhood.

The following is the trailer for Julia Kwan’s documentary “Everything Will Be,” a film that explores the rapidly changing Chinatown.

“When the horse dies, you walk on the ground. No matter how difficult, one must keep walking.”

So, what is home? I think it’s a place where you can firmly root yourself, where you’re welcomed and comfortable. For many, I don’t think the concept of home truly exists.

I’ll leave you with these questions (since I feel I’ve veered off of the prompt quite a bit): What do you think of gentrification? Do you agree that it destroys homes, cultures, and community? Or do you think it’s a necessary development, an investment, the natural progression of things?

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Reimagining Home and Sacred Space. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2004. Kindle ebook.

Everything Will Be. Dir. Julia Kwan. National Film Board of Canada, 2014.

Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee on Homelessness. (2014). Results of the 2014 Homeless Count in the Metro Vancouver Region.

“Keefer Block.” Vancouver Condo. Web. 23 May 2015.

Hi!

I loved your blog, great use of visuals! I am at the Okanagan campus so I found the pictures very helpful. I think that gentrification has proved itself to harm those who originally lived there. Chinatown in Vancouver is not only an enriching area, it is a historical area and should be preserved for generations to come. Gentrification displaces those who should have rights to not be displaced.

However, on the other side of the coin, cultures do change and shift overtime and a sense of community will prevail in gentrified areas and the new areas that gentrified people move to. Although gentrification may displace the existing culture in the area, a new culture moves in so I do not think that culture is “lost” during gentrification as everyone has a unique culture regardless of their income or status. Culture exists in all of us!

I do think that improving a neighbourhood and revamping areas is important but my problem is the way that urban builders are doing it in Canada thus far. Sprucing up a neighbourhood should be done for the existing community, and not with the intention to displace and harm.

Here is an article by Dr. Carlos Teixeira http://neighbourhoodchange.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Murdie-Teixeira-2011-Gentrification-Toronto-Little-Portugal-UrbStud.pdf on some of the effects gentrification has had on Toronto.

Cheers!

Hi Alyssa,

Thanks for your response. I totally agree that cultures experience a shift over time, and I agree that community still exists (in some degree) in gentrified neighbourhoods. But I disagree with your statement that culture isn’t lost when communities are gentrified. Although a new culture moves in, the disappearing of an old culture signifies, to me, the death or at least weakening of that culture.

But I absolutely agree with your statement that sprucing up a community should mean working with the existing community, not pushing them out.

🙂

I really enjoyed this post, Melissa! Gentrification in Vancouver is something I’ve often thought about. I’ve worked with the Powell Street Festival Society, which holds an annual Japanese cultural festival in the Downtown Eastside, so I’ve had the opportunity to see at least an example of the effect of pushing groups of people out of their “home” (both with the historical Japanese community and with the DTES community).

The biggest issue I have with gentrification is that I feel it displaces the original community, and tries to sweep a bigger problem of homelessness under the rug. While I (kind of) understand that businesses need to expand and grow, it gives priority to capitalism, rather than a growth of community. And often I find there’s either little respect for the original cultural community, or else they’re trying to offer a new spin on it (ie. a Chinese fusion restaurant in Chinatown) when, really, why can’t an authentic Chinese restaurant work there?

However, I was walking through Chinatown recently with my family, and my mom was lamenting about when her family used to live in Chinatown, and how desolate and deserted it is now compared to when it was a thriving neighbourhood. It might be because rent prices are too high now due to popularity and “hipness” of the area (I’m not familiar with finances and real estate) but there are a lot of space that are unoccupied or up for rent. If the liveliness of the neighbourhood isn’t happening “organically”, is there a danger to introducing a new community? Perhaps the original occupants have spread out, and there really is just less of a community than there used to be?

I’m definitely not saying that one way or the other is right—there’s a lot to think about! Thanks for your thoughts. I look forward to reading more from you!

Hi Whitney,

You’re right that gentrification makes it too expensive for many longstanding businesses to stay open, which is why you notice lots of vacancies in areas like Chinatown. I would argue that if the neighbourhood still remained affordable, it would be lively. Many long-term residents, mostly Chinese seniors, are being priced out of their own homes and businesses.

The Tyee did a fascinating series about Chinese seniors being displaced because of gentrification. Worth a peek: http://thetyee.ca/Series/2013/04/01/Chinatown-Seniors/

Thanks for sharing the article!

🙂

Hi Melissa,

I really enjoyed reading your blog. I had only briefly heard about the UBC Learning Exchange, so it was interesting to learn about all the good work that occurs there!

The problem that I have with gentrification is that I feel that it sanitizes places of memory, and rewrites them to reflect Vancouver’s image as a dream world class city. In this case I am referring to the DTES and the missing and murdered Indigenous Women who were victims of Robert Pickton. Vancouver is seen as a city mapped in memory, which is emphasized by David Harvey’s expansion of the theory of “genius loci” (guardian spirit). He argues that buildings and places absorb relations that occur within them, and it determines the essence of one’s identity. Although these places hold traumatic memories for victims and their families, to break them down would trivialize what had occurred. The places continually serve as a reminder of the past, making the victims experiences visible, while also showing the negligence of those who made little effort to solve the crimes.

Gentrification is bound to occur and will probably destroy places of memory. Thus, it begs the question of how we should carry our pasts with us? Events such as The Annual Women’s Memorial March that occurs in the DTES to call attention to missing and murdered Indigenous women has attempted to do this. They remap memory and space by stopping along the way to commemorate where the women were either last seen or found.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/women-s-memorial-march-in-vancouver-attracts-hundreds-1.2957930

Looking forward to your next post!

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for this! I love your description of gentrification sanitizing places of memory — what a great way to put it. Vancouver is notorious for trying to push issues under the rug to appear more desirable to outsiders looking in. I also really love Harvey’s genius loci theory, very beautiful and a great reminder of the importance of history and preservation.

I think the Women’s Memorial March is a terrific way of commemorating the missing and murdered Indigenous women. It’s so important for us all to ensure their memory does not get washed away.

Thanks so much!

🙂

Hi Melissa! This is interesting how you bring Chinese signage as an act of colonialism. I have never really heard about complaints of Chinese signs disappearing from the Chinatown, which is fascinating to me because the reverse is true in Richmond’s Golden Village, so much so that the city of Richmond has considered measures to eradicate Chinese-only signs and to enforce English on all signs to accommodate everyone.

I wonder why you believe that the “Chinese people’s land” is being taken away, while you don’t think that any group (particularly white people) have a right to settle anywhere and call the land their own? More importantly, I think the current dialogue and pressing concern about housing in Vancouver has to do with foreign ownership, usually from mainland China, and how it is pushing out residents to more affordable parts in the city. At least white yuppies are actually living in the communities and participating in them (whether or not those activities align with the original identity of the neighbourhood); in the case of foreign ownership those properties are left vacant, and people often complain that this is the reason why the neighbourhood loses its vibrancy and becomes a ghost town. Therefore, I believe that the problem isn’t really one of white gentrification, and that we need to be careful when we hold one group accountable for a problem for which we may all found ourselves complicit in perpetuating.

Hi Timothy,

I don’t think I said anything about white people not having the right to settle on a “land of their own”, though I do want to know what you mean by that. What is their own land? These are Unceded Coast Salish Territories…

Gentrification and foreign ownership are different issues. Upper-class neighbourhoods like Coal Harbour have the highest vacancy rates due to foreign ownership (http://www.vancouversun.com/Foreign+ownership+highest+downtown+Vancouver+condos+CMHC+report/10658524/story.html), not Chinatown and the DTES. The dictionary definition of gentrification is “the buying and renovation of houses and stores in deteriorated urban neighbourhoods by upper- or middle-income families or individuals, thus improving property values but often displacing low-income families and small businesses.” So, when it comes to gentrification, foreign investors aren’t the problem, upper- middle-class people investors, home-buyers, and business owners who fail to consult or consider the community when they move in are the problem. They’re the ones renovicting people on welfare from old SROs to market the spaces to “artists”, they’re the ones opening trendy shops and restaurants that push the low-income people out. Yuppies aren’t participating in the communities, they’re completely changing the communities, destroying whatever culture exists and replacing it with another needless coffee shop.

Forgive me for being blunt, but I would argue that yuppies hardly make a community vibrant. People who move into communities and try to work with them, people who go into an existing community and don’t try to change it to suit their own needs — and yes, this does include white people — these are the people who keep communities vibrant.

This quote from a 2013 Mainlander article is poignant:

“So why is the “foreigner thesis” so popular among Vancouver’s political elite? One answer is that it allows the government to get away with its anti-affordable housing policies. Property-owning elites such as Mayor Robertson continually go on record to “lament wealthy immigrants making ‘green’ city unaffordable.” Why? Because it allows Vision Vancouver to serve the rich, displace the poor and deregulate the housing market without any consequences.”

You’ll also read in this Mainlander article that foreign buyers aren’t “mostly from Mainland China”.

http://themainlander.com/2013/03/25/empty-condos-and-foreign-investors-sign-of-the-times-or-synonyms-for-racism/

I’d even argue that the big problem with housing prices going up isn’t foreign investment, it’s speculation (though I know very little about the real estate market). Here’s what Bob Rennie, Vancouver’s “condo king” has to say: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/vancouver-condo-king-bob-rennie-calls-for-tax-on-speculation-1.3085211

What I’m trying to say is that foreign ownership isn’t pushing low-income residents out of their communities, it’s the upper- and middle-class buyers and business owners who are changing the landscape of these neighbourhoods, making them more desirable, selling 10 dollar coffees and 50 dollar entrees that local residents can’t afford, and pushing original residents out of their homes and far into the suburbs.

Thanks for reading and commenting with some interesting input. Cheers!

🙂

Hi Melissa,

I think this is a great meditation on the meaning of home, especially in the context of economic displacement. I don’t agree that the gentrification of Chinatown is “just like” Indigenous people’s land being taken away – after all, Chinatown is still on the unceded ancestral territory of 3 Coast Salish nations, so this is not equivalent – but I take your point that the cultural makeup that has defined the neighbourhood for generations is changing in a way that seems beyond local control. Thinking about your questions more specifically, I would characterize gentrification as an ‘unnatural’ progress – somehow predictable in the face of endless machinations of capitalism, but definitely contrary to community health and well-being.

If I can hazard a generalization about the mobility of people in modernity – we are less likely to live where we grow up, to share a house/land for generations, etc. – can urban centres maintain neighbourhoods like this anymore? Ones with distinct cultural/ethnic identities, or is all local character washed out by artisanal cocktails/snacks/coffee, etc. and other trends (that will eventually run their course)?

Hi Heidi,

Thanks! You’re right, it’s not the same thing — I didn’t word that thoughtfully, thanks for callin’ me out.

On that note, have you heard of the documentary Cedar and Bamboo? It explores the intersecting lives of Chinese immigrants and Indigenous people in Vancouver, touching upon many shared experiences between both cultures through stories told by mixed-race descendants. Here’s the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zh1qYSwfTaU

As for the second part of your statement, it seems like neighbourhoods like this can no longer thrive because gentrification is the norm. Just curious — why do you think we’re less likely to live where we grow up?

Cheers!

🙂

Hi Melissa,

I really enjoyed this blog! I wonder if the rationale behind the owner of somewhere like Pidgin, apart from the obvious advantage of buying cheaper land, has anything in common with Chamberlin’s narratives of Us vs Them. I can see the colonial justifications that opening a hip fusion restaurant would both bring culture to a “barbaric” area and make use of land that is otherwise “useless” at play there. Of course, if gentrification’s endgame is mega-corporation takeover, as you suggest, that seems to create a situation in which any culture or “usefulness” the original gentrification has created disappears. The whole process seems to me to be needlessly destructive and self-defeating.

Hi Max,

Thanks! I totally see the Us vs. Them mentality at play in gentrification. The process really is needlessly destructive and that’s what is so so so frustrating about it.

🙂

Hey Melissa!

This was a wonderful blog post and beautiful blog too! As an Asian, it really pains me to see what Chinatown in Vancouver has become. Out of all the Chinatowns I have been to (and trust me, I’ve been to MANY haha), Vancouver’s really pales in comparison in terms of a rich culture or heritage because of the constant displacement by your aforementioned ‘establishments’. Although I must admit that I am a regular patron of PiDGiN, I see that many places are not fitting in within what is traditional and go against the preservation of culture. For the changing climate which embraces ‘being hipster’ to a larger extent, what was traditionally home to the local meat store is being replaced by The Ramen Butcher or even Fortune Sound Club- basically anything which goes against the ‘glamor’ as offered traditionally by neighbourhoods such as Yaletown. Tourists interested in finding out more about Chinese culture are sidetracked by venues such as The Keefer Bar instead of cramming it with the locals at Phnomh Penh for example. Although I believe change or improvement is necessary to stay relevant, the preservation of culture is definitely something which needs to be worked on, instead of people knowing that The Sun Yat Sen Garden exists simply because its on the way to Bestie! Instead of ‘Us vs Them’, perhaps (and I am not too sure how tangibly this would work out), more dialogue between the traditional residents and the City themselves could encourage gentrification for those who are in need, instead of making Chinatown a stomping ground simply for the deviant ‘edgy’ crowd of today!

Hi Debra,

Thanks for replying. I absolutely agree. Change is inevitable and improvement is often necessary but it’s important that we work with the communities, not exclusively toward things that only benefit us. I wonder how we can effectively make changes in these communities without pushing people out… Seems inevitable now.

Thanks!

🙂

Hey Melissa, thanks for directing me to this post. Gentrification is something I’ve been thinking a lot about lately, as I’ll be (finally) moving out of my parents’ house when I graduate from UBC. As a would-be middle-class, university graduate who has patroned Matchstick Coffee and Nelson the Seagull, I want to understand fully how it works and how I might alleviate the problem should I end up in a gentrifying neighbourhood.

On one hand, I understand how it displaces those who can only afford to live in those areas and of course the unique culture that has taken root there. On the other hand though, where should educated university graduates, who are just starting out, live when yes, they have more privilege, but they also can’t afford Vancouver’s skyrocketing housing prices? Should these young professionals/”yuppies”, stuck in the in-between, only live in these places temporarily; should they not move to these places at all?