We watched the American Sniper in our most recent ASTU classes. The film is based on a US Navy SEAL sniper Chris Kyle’s life, with a focus on his deployment in the Iraq War.

Throughout the term, we have read several scholarly articles and have been introduced to their ideas. The scholars Judith Butler and Joseph Darda influenced my understanding of American Sniper. Judith Butler’s theory of precarious lives argues that all lives are vulnerable (“precarious”), but some lives are more vulnerable than others (“precarity”). She believes that since we share this vulnerability, if we are able to recognise this common ground, it may be possible that we find solidarity and hopefully find peace. Butler also prompts us to consider who’s lives we find grieveable. She believes that if we could recognise this shared grief as commonality, it may help us find peace. Connecting to American Sniper, I see a lot of violence and hatred of Chris Kyle and his fellow American troops towards the Iraqis. For example, the Iraqis were spoken about as “savages” and “evil”. I remember recalling Butler and thinking that if only all sides could pause, and recognise our mutual humanity, that the other sides’ lives are grieveable. That in war, all sides suffer. I don’t think violence can’t be the way out, because it breeds more anger.

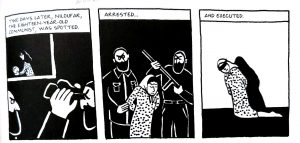

This connects to Joseph Darda, who speaks of the “fantasy of mastery”. This is where when one feels vulnerable, one may make attempts to eliminate their vulnerability through war, which only results in continuing cycles of violence. I see this in American Sniper where the event of 9/11, which Chris Kyle sees on television, gave him a stronger reason for military service. The 9/11 event was a violent event, and Chris Kyle’s personal bellicose response and the US’ response of war exemplifies this cycle of violence.

My first-year studies have greatly helped me to think critically about American Sniper. Unfortunately, it is always easier said than done, and my skills need to further development. In our classes (ASTU and others), we have become acquainted with different scholars’ theories, concepts and analyses over a text. I think that knowing what other scholars have said or interpreted provides me with a lens to view the texts we read. The scholars often bring ideas that I might not have thought of, and inspire me to build on what they have said on a related tangent. They prompt me to consider my ‘position’ – whether I agree with the scholar or not.

Moreover, knowing what other scholars think enable me to see beyond the surface. Instead, it allows me to notice and consider the different levels of understanding and interpretation. To give an example – Patrick Deer’s observation of the militarization of everyday, civilian life – that there is a blurring between the warfront and society. If I had not read Deer, I would have passively watched American Sniper and likely forget most of it. However, having read Deer and been prompted to think deeper, I took note of moments in the film where I could see examples of this – such as Chris teasing his wife in the kitchen with a toy gun at the end of the film.

Finally, reflecting on the other ASTU texts, I see a connection between the other texts on the syllabus. The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Juliana Spahr’s poems, the American Sniper, and Redeployment seem to portray the story of 9/11 and its aftermath in a sequential way. In Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, we see America before 9/11, the event of 9/11 itself – which sparked the “War on Terror” – and the immediate response in America – the rise of a fearful and nationalistic atmosphere. Then, in Juliana Spahr’s poems, we wait with Spahr to see whether there will be upcoming wars. This links to the film American Sniper, where we see Chris Kyle in Iraq, the home front response, and portions where Kyle is back in the US. The short story Redeployment ends this narration as we follow Sergeant Price home from the Iraq War. We are given an insight to the thoughts of a returning soldier, and the disconnection between a veteran and civilian life. I am glad to have a greater understanding of 9/11, its aftermath, and much broader implications through the different texts and scholarly articles that we have read. Thank you for this journey.