Last Call: Final Reflections on Life Narratives, Hybridity, and Representation

Over the course of this year, we have studied in depth the power of the life narrative to act as a platform for marginalized voices to challenge the socio-political hegemony that so often silences them. By publishing counter-narratives that challenge dominant tropes about disability (as seen in Ryan Knighton’s Cockeyed), sex work (discussed in Maggie De Vries’ Missing Sarah), raciality (taken up in Fred Wah’s Diamond Grill and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis), and other such topics, these life narratives are vibrant affirmations and reclamations of identity that is often misunderstood – and therefore misrepresented – by society.

The concept that stands out to me the most as I reflect upon the aforementioned life narratives is the concept of the “hyphenated” identity, which I take up in my previous post. Fred Wah explains that, although the hyphen is “literally about being racially mixed” (178), the application of the “inbetweenness” of hybridity is not limited to race alone (179) – it can apply to other spheres as well. Reflecting on this concept, I notice that each of the stories we have studied (these being Cockeyed, Persepolis, Missing Sarah, and Diamond Grill) are written by those who each come from their own place of hybridity. Furthermore, I notice that each author claims their hybridity and reveals how it differs from the identity establishments assigned to the author by society: they break the cages of generalization that cover so many groups and individuals. As they challenge their respective ‘prescribed’ identities, these authors remind me that it is impossible to generalize the story and identity of an individual by their appearance, social sphere, or socioeconomic standing. Each author speaks to their own uniqueness within the context of wider collective groups, rescinding efforts by dominant narratives to silence them.

For example, in Cockeyed, Knighton discusses his life under the diagnosis of retinis pigmentosa, where he wrestles with semi- to full-blindness and thus lives between the worlds of the blind and the sighted. In the final chapter, “Losing Face”, Knighton describes his transition from expressing emotions facially to expressing and absorbing expression through his other senses. Knighton presents this description in a way that compares the two forms of expression, but accepts his own inbetweenness rather than longing for another reality. “My face characterizes me as serious and dour… according to my students.” Knighton writes (256). “But that isn’t how I feel… I’m not indifferent… from the world around me but from my face itself” (Knighton 256). Here, Knighton presents the generalization given him by his surroundings and refutes it by revealing his reality. He claims his in-between identity as his own.

Similarly, in Persepolis, Satrapi challenges the perception of Middle Eastern populations as being ‘savage’ in the way she frames her story “dieglectically” (Chute 97) from a child’s point of view. I suggest that the connotations of innocence, blunt social justice, and dreamlike thought are intertwined with the concept of a child; thus, a story told from this perspective (and with these connotations) inherently reveals the existence of individuals who are not war-hungry, or corrupt, or brutally violent. Satrapi’s story outlines the trauma experienced by the Iranian population at the hands of a group of extremists – not the trauma experienced by a nation of savage warriors. Satrapi, living between the worlds of extremist revolutionaries and socialist families, says that she “won’t ever forget” who she is (148), no matter where she ends up. I suggest that she finds her place as a socialist revolutionary of her own kind: fighting against extremism, and against brutality.

Finally, in De Vries’ Missing Sarah (which I also discuss in a previous post) De Vries actively deconstructs societal misrepresentation s of sex workers – specifically of her sister, Sarah, who lived between the worlds of white-walled, middle- to upper-class West Point Grey and the poverty-stricken Downtown Eastside in Vancouver. In the very prologue of the narrative, De Vries explicitly shares her purpose for writing this narrative:

“If we can start to leave the gritty image of the sex worker behind and begin to see real people, real women, to look them in the eye and smile at them and want to know who they really are, I think that we can begin to make our world a better place for them and for us, for everyone.” (De Vries xv)

This quote, I think, is applicable to any marginalized or stigmatized group or individual, including those authors of Persepolis, Cockeyed, and Diamond Grill. The life narrative provides an incredible platform for these individuals to share their stories: to humanize themselves as “real people” (De Vries xv) in the eyes of society – however appalling it is that this must happen in the first place.

As I read each of these life narratives this year, these generalizations about marginalized populations (which remove any sort of individuality to those who might fall under discriminatory umbrella terms like “sex worker”, “terrorist”, or even “blind”) became so much more apparent to me, and were deconstructed for me in powerful ways. I was made much more aware of the complexity of the hyphenation that affects so many in such a variety of ways. Ultimately, my understanding of the important work of life narratives in the wake of these complex counter-narratives has deepened significantly, and my hope is that a broader audience will take up an acknowledgement of, and an interest in, the important work of self-representation in this literary platform.

Works Cited

Chute, Hillary. “The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis”.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36.1/2, Witness (2008): 92-110. Print.

De Vries, Maggie. Missing Sarah: A Memoir of Loss. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2008. Print.

Knighton, Ryan. “Losing Face.” Cockeyed: A Memoir. New York: Public Affairs, 2006. 255-261. Print.

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis. New York: Pantheon Books, 2003. Print.

Wah, Fred. Diamond Grill. Edmonton: NeWest, 2008. Print.

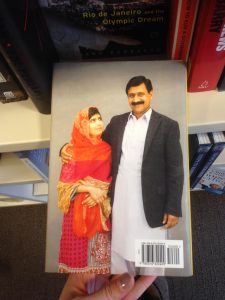

er clothing is still eye-catching, but now it is the direction of her gaze that communicates the significance of this picture. Here, Malala is portrayed through a more ambitious lens: she looks admiringly at the man who fuels and empowers her fight for women’s education and equality. Because her father is a symbol of perseverance, Malala is not only gazing at a family member but at the embodiment of her goals and dreams; she is focused on her reason to push through the seemingly insurmountable obstacles she faces. Similarly, it is not merely her father who stares proudly into the camera, but perseverance itself. This is striking, as it projects an image to the world of confidence and persistence in the face of extreme adversity.

er clothing is still eye-catching, but now it is the direction of her gaze that communicates the significance of this picture. Here, Malala is portrayed through a more ambitious lens: she looks admiringly at the man who fuels and empowers her fight for women’s education and equality. Because her father is a symbol of perseverance, Malala is not only gazing at a family member but at the embodiment of her goals and dreams; she is focused on her reason to push through the seemingly insurmountable obstacles she faces. Similarly, it is not merely her father who stares proudly into the camera, but perseverance itself. This is striking, as it projects an image to the world of confidence and persistence in the face of extreme adversity.