In Maggie de Vries’ narrative Missing Sarah, de Vries creates a space for her murdered sister Sarah, a sex worker on the Downtown Eastside, to share her experiences by including excerpts of Sarah’s journal in the narrative. In an excerpt on page 180 of Missing Sarah, de Vries includes an entry which describes the slow degeneration of Sarah’s identity as she works on the streets, illuminating the deep detrimental effects of perpetually enforced societal stigmas on an individual’s sense of self. This deterioration is encompassed by Debbie Wise Harris’ concept of “strategic silences”, as discussed in Yasmin Jiwani and Mary Lynn Young’s article Missing and Murdered Women: Reproducing Marginality in News Discourse. Sex workers are silenced by these societal stigmas, and are thus represented as unworthy in the eyes of the public.

In her journal entry, Sarah describes the deep, traumatic transformation of identity she experiences as a sex worker in Vancouver by means of a careful choice of diction. First, Sarah employs words that describe the loss of her old self – “erosion,” “deadening,” “lost cause,” and “nothing” (de Vries 180) – emphasizing not only a loss of identity, but also of the hope of ever returning to it. Earlier in Missing Sarah, de Vries states that “girls don’t start defining themselves as prostitutes overnight” (76) – they only embody this identity once they turn their first trick. This change is time-consuming, and one can thus assume that it is a perpetual transformation of a sex worker’s concept of self. Sarah describes her new identity with terms such as “dirty, slutty, and cheap,” as well as “whore” and “junkie” (180) – all of which are derogatory terms. Sarah says that these are terms by which she labels herself “now” (de Vries180) – but as a result of what?

This question brings us to reality: the identity of a sex worker is dictated by societal stigmas. Operating under the assumption that humans are socialized into rather than born with identities, it is impossible for a woman to label herself as a “whore” or a “junkie” from the minute she develops thought and speech. No: these are derogatory societal stigmas which perpetuate the perception that sex workers are, to use Sarah’s choice of diction, “dirty, slutty, and cheap”. Over time, as Sarah faced these stigmas daily, she evidently internalized these opinions of herself, thus experiencing the aforementioned “erosion of feeling” (de Vries 180). It is at the point of this internalization that the concept of “strategic silences” comes into play. Although Jiwani and Young discuss stigmas surrounding Aboriginal sex workers, this theory can also be applied to any sex worker. The authors state that, as sex workers are silenced by societal stigmas, their backgrounds are forgotten. This contributes to their representation in society as “deserving of violence” (Jiwani, Young 899), for their families, friends, and personalities are disregarded.

In sharing her experience of identity loss and transformation, Sarah is able to speak on behalf of sex workers to humanize their experiences and defy these strategic silences. Her testimony acts as a warning against the internalization of these stigmas, and it points to a deep need for change in society’s treatment of those working in the sex industry.

Works Cited

De Vries, Maggie. Missing Sarah: A Memoir of Loss. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2008. Print.

Jiwani, Yasmin, and Mary Lynn Young. “Missing and murdered women: Reproducing marginality in news discourse.” Canadian Journal of Communication 31.4 (2006): 895.

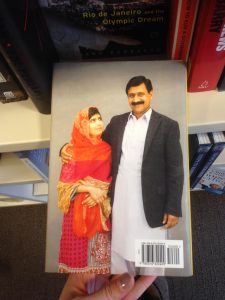

er clothing is still eye-catching, but now it is the direction of her gaze that communicates the significance of this picture. Here, Malala is portrayed through a more ambitious lens: she looks admiringly at the man who fuels and empowers her fight for women’s education and equality. Because her father is a symbol of perseverance, Malala is not only gazing at a family member but at the embodiment of her goals and dreams; she is focused on her reason to push through the seemingly insurmountable obstacles she faces. Similarly, it is not merely her father who stares proudly into the camera, but perseverance itself. This is striking, as it projects an image to the world of confidence and persistence in the face of extreme adversity.

er clothing is still eye-catching, but now it is the direction of her gaze that communicates the significance of this picture. Here, Malala is portrayed through a more ambitious lens: she looks admiringly at the man who fuels and empowers her fight for women’s education and equality. Because her father is a symbol of perseverance, Malala is not only gazing at a family member but at the embodiment of her goals and dreams; she is focused on her reason to push through the seemingly insurmountable obstacles she faces. Similarly, it is not merely her father who stares proudly into the camera, but perseverance itself. This is striking, as it projects an image to the world of confidence and persistence in the face of extreme adversity.