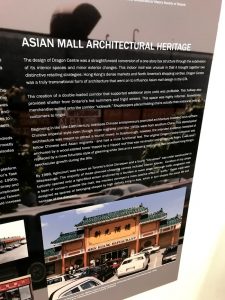

Cultural identity is expressed through ethnic retailing. Qadeer explains that immigrants shape how the city is built by creating places that serve their needs (2016). As Howard Tam explained to us in his lecture, the mall was always designed with Chinese people in mind (personal communication, October 1 2019). Not only is the original optometrist still open for business, it is featured prominently in the space along with herbal medicine stores. The mall also had the dim sum restaurant as the anchor of the mall rather than the grocery store as is typical in Western malls. The mall’s layout is based on a blend of Hong Kong’s dense markets and North America’s shopping centres (see Figure 1, exhibition materials, 2019). It’s an example of how, as Qadeer puts it, community cultures are becoming more hybridized in North America (2016). We are learning and borrowing from each other. Yet there are limits to this. The population generally remained divided along racial lines on the mall’s development.

Despite this, this place meant a lot to its users. There’s the story a woman told in the sharing circle of her experience working at Z’s Hair Salon in the mall between 1985 and 1989. She reminisced about how people greeted each other, and how loud and alive the mall was. She told us of how hair stylists used to buy outfits at a fancy German boutique in the mall and, despite not being able to pay for them in full, the boutique allowed for payment in instalments. This internal community indicates a sense of place and belonging amongst Dragon Centre merchants. This story also highlights the importance of presenting yourself well at the mall. The storyteller added that the customers would judge the stylists by their outfits. As a destination at which to see and be seen, the importance and relevance of the mall to both shoppers and merchants becomes strikingly clear.

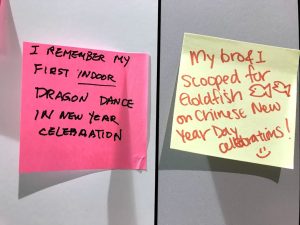

New Year’s celebrations also featured prominently in the stories people shared. One anonymous person wrote ‘My bro and I scooped for goldfish on Chinese New Year celebrations!” while another shared, “I remember my first indoor dragon dance at the new year’s celebration” (see Figure 2, exhibition materials, 2019). The importance of this mall as the first indoor Chinese mall remains in the second storyteller’s mind to this day. It is also clear that the mall was a gathering place for the Chinese community, a place to unabashedly celebrate their heritage in a time of vicious hatred from non-Chinese locals.

These stories connect people who experienced this mall in its heyday. As a non-Chinese person, I felt slightly alienated while visiting the mall. I was stared at as I entered the building by Asian people at the entrance. It seemed to me like they were identifying me as white and seemed curious to see outsiders, likely both at the mall and at the event. The Dragon Centre’s reach stretched far past the Chinese community in Agincourt, though, so it is possible that, if I were older, I could have had memories at the mall. A surprising moment came when an Asian man stopped by the walking tour and asked me what was happening there. It struck me as unusual that he would ask me, a young white woman, for details of the event, but I was happy to oblige.

Figures

Figure 1- the exhibition material highlighting the mall’s design elements

Figure 2 – Stories from the Dragon Centre Commemoration Celebration event

References

Exhibition materials. Dragon Centre. October 5 2019. Dragon Centre Commemoration Celebration. Scarborough.

Qadeer, M. (2016). Multicultural Cities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.