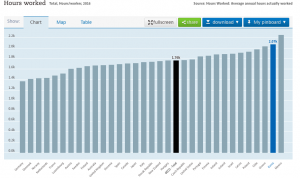

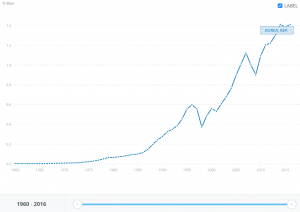

According to a recent study done by the Economist, South Korea ranks last on the issue on the working environment for women this is compared to the other 29 countries who are members of the “Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development” (OECD). This is based on each countries: educational attainment, labour-market attachment, pay, child-care costs, maternity and paternity rights, business-school applications and representation in senior jobs (such as managerial positions, company boards, and parliament). Unsurprisingly Korean managerial, company board, and parliament positions for women are among the lowest levels in the OECD countries. Coming way below the OECD average. This gender disparity is easily exhibited in the Korean Drama Misaeng, by just looking at who holds the top positions in the company, One International. For instance, in episode 4, Sun Ji-young is the only high ranking female present for the intern presentations. This at first made me think that she was the only high ranking female at One International. However, in episode 7 we are introduced to the only other high ranking female employee and that is the Finance Department Manager, Kim Sun-Joo. Their isn’t even a single female CEO present during team 3’s project proposal presentation in episode 13. This is a fairly accurate depiction of the power gap between men and women.

This gender disparity for senior jobs in Korea has been noted to have had a serious impact on ‘sexual harassment’ in the workplace. In fact, “according to the survey conducted by the Federation of Korean Trade Union, a conservative umbrella union here, eight out of 10 assailants were the boss of the victim, followed by co-workers and clients.” Many ‘sexual harassment’ offenders are those at the “pinnacle of industry hierarchies.” However, just being higher up than a female co-worker can encourage men to commit ‘sexual harassment.’ This is a systemic issue in Korea, not just a few individuals. As John Dalberg-Acton once said: “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Men in Korea have had a long stretch of almost absolute power over women and only in the last couple of decades has real change occurred, that has given women more freedoms and rights. In this paper, I am going to talk about how Misaeng reveals that ‘sexual harassment’ in the workplace is caused by gender disparity, specifically in high positions within Korean companies. As a lack of representation from women in higher sectors, forces women in lower ranking positions to remain passive towards acts of discrimination. This is especially the case, as Korean society is largely patriarchal in nature. And many Korean men still hold on to this gendered-status power gap. Most importantly, this paper will connect both the fictionalized issues shown in Misaeng with real events and issues dealt within Korean society on ‘sexual harassment.’

In Misaeng, the worst offender for abusing their power over female employees is, Department Head Ma Bok-ryul. A year before the drama’s storyline even began, Department Head Ma already had a record of sexually harassing a female employee. This resulted in him being brought up on charges and getting a three month pay cut. However, even though he has paid a penalty for his actions, he still hasn’t changed his attitude towards women. In fact, he might have gotten worse. This may be due to the fact that he has maintained his position as Department Head, a position that gives him authority over many women who work at One International. Department Head Ma has used his power over Ahn Young-yi, on numerous occasions, for example he ordered her to reject her own proposal that had been approved by headquarters, in order to get a promotion for himself. He has stopped her from leading meetings for projects that she had been in charge of and had already done the work for. He constantly blames her (or women in general) for any failings that occur in the resource team, even when it was another co-workers fault or was outside of her control. Not because she is incompetent but because she is a woman.

This isn’t just something that only happens in k-dramaland but also in real life. Though Misaeng is a work of fiction, often its plot payed tribute to real events or issues faced in Korea at the time. Most notably, in episode 14 of Misaeng, two conversations between Ahn Young-yi and Department Head Ma Bok-ryul seem to be alluding to an actual case of sexual harassment that occurred in South Korea. The case in question took place on Thursday, September 11, 2014 between seventy-six year old National Assembly Speaker, Park Hee-tae and a twenty three year old female caddie, while playing a round of golf. The caddie claimed that Park made inappropriate physical contact with her; which resulted in her requesting to be replaced and substituted with a male caddie. Later, Park even partially admitted to his behaviour by saying that he “poked her on the breast once.” However, he claimed ignorance to the effect he had on the caddie stating that “she didn’t express displeasure at the time.” And that his intentions were non-licentious in nature, as “he has granddaughters and that when he meets women of a similar age, he shows them affection and tells them they are pretty.” He also gave unsolicited advice that she should “beware of men because she was beautiful.”

One of the conversations that alludes to this event in Misaeng, happens while discussing a future work-related golf trip between Department Head Ma and the director of Samjung. While Young-yi is going over details, Department Head Ma interrupts with a crass remark that all they need are “pretty caddies.” In reply, Young-yi informs him that she requested male caddies because the purpose of golfing was business. Department Head Ma then changes the subject to Young-yi’s personal life. Making comments on her relationship with Shin Woo-hyun from Samjung and questioning her behaviour.This conversation is an obvious reference to the sexual harassment incident mentioned above; which is later echoed in the next confrontation between Young-yi and Department Head Ma. The encounter begins with Department Head Ma walking in on Young-yi talking with Jang Baek-Ki. He then goes off on her, questioning her behaviour towards him and other men. Even implying that her actions are indecent and may be perceived as promiscuous. He ends his rant with the statement, “I’m worried about you because you’re like my daughter.” When Young-yi questions that statement, Department Head Ma gets defensive and says “Are you accusing me of sexual harassment?” And attempts to throw coffee at her. The key details that connect the two conversation’s in Misaeng and the Park Hee-tae sexual harassment incident are Department Head Ma’s remarks on the appearance of the caddies, his imagined correlation between his treatment and words to Young-yi with that of a daughter, his gratuitous advice on behaviour towards men and lastly Young-yi’s action of setting up male caddies instead of female ones. For those reasons, both the real interactions between Park Hee-tae and the female caddie and the fictional interactions between Department Head Ma and Ahn Young-yi are prime examples of cases where someone in a powerful position, abuses said power, resulting in the ‘sexual harassment’ of a woman at work.

Another person Department Head Ma clashes with often is Deputy Department Head, Sun Ji-young. She is truly a role model for working mothers. She manages to balance having a daughter as well as being one of the highest level female employee in the company. However, her status does not protect her from Department Head Ma’s crude words and disrespect.Which also makes her proof that even women in powerful positions are often harassed by male co-workers. For example he once during an argument told her: “I’ve been lenient with you because you’re a woman. Hey, you should be grateful to your husband who can bear with living with someone like you.”But Sun Ji-young doesn’t take his words lying down and usually has a well thought out comment to put him in his place. Like when she cooly replied back to him that: “with two cases of sexual harassment, you wouldn’t just end up with pay cut.” Though she doesn’t have as much power as Department Head Ma, Sun Ji-young still can fight back which is something Ahn Young-yi really can’t do. However if their were more women in higher positions, it might make it easier to protect lower level employees from people like Department Head Ma.

However to do this, you would need to change the mindset of many Koreans, especially on what is considered appropriate behaviour towards women. This would be a challenge as Korea is a largely patriarchal society—meaning men have a lot more status and power than women. And this is something that can be easily abused by even the most well-meaning men or harmless looking men. For instance, Han Seok-yul is one of the more lovable characters of Misaeng, largely because of his flamboyant personality, strong work ethic, incredible skills as resident gossip, and enduring will to fight for injustices. His constant dramatics allow him a key role as comic relief for the often dreary workplace environment of One International. However he has his flaws as he can be kind of a suck up, a little too nosy, and sometimes annoying to fellow co-workers. His love of fabric and women along with his lack of respect for the boundaries of others, has often gotten him into trouble. Most notably, in episode 3, when Seok-yul harasses an unnamed female employee at a fabric factory. The situation starts with Seok-yul briskly walking behind the female employee. He then grabs her arm and asks to touch the material of her skirt; but he doesn’t wait for a reply and instead gropes her behind. She then slaps him in the face and tries to walk away; but he repeats his action of grabbing her arm and asking for permission to touch her skirt. This time she doesn’t hesitate and slaps him again, managing to get away in the process. Yet, as serious as this incident is, the scene is presented as comical. Making in my opinion, a sort of mockery of sexual harassment.

I found this scene reflective of educational videos, released after the 1999 legislation on ‘sexual harassment,’ that Lee Sung-eun described in his article. Apparently, they were 20 minute long videos made by the Ministry of Labour, which “superficially descib[ed] the types of sexual harassment, such as verbal and physical abuse.” In fact, the videos seemed “to make light of sexual harassment as comprising humorous and inconsequential incidents in the workplace.” This mindset seemed to be encouraged, as the characters in the video were played by comedians. This use of comedy to discuss such a crucial issue in Korean society doesn’t send the right message to viewers. Instead, it promotes people to adopt a humorous or blasé attitude towards it, undermining the videos purpose. This is attitude seems to have been mimicked in Misaeng which as a whole seems to promote the equality of women, yet the scene with Seok-yul seems to sabotage that message.

Whether the current attitude of men in Korea has any connection with the failed content of the Korean government’s early attempt at ‘sexual harassment’ education videos, is unknown. However, it is clear that ‘sexual harassment’ can be a source of humour for men, as shown in episode 10 of Misaeng, when Park Jong-sik and Sung Joon-sik enjoy making the women in the break room uncomfortable with their sexual comments towards them. The situation goes began when Park Jong-sik and Sung Joon-sik arrive in the break room with their coffee. Park Jong-sik notices three female co-workers including Shin Da-in, a member of the steel team. Park Jong-sik makes a comment that in his opinion “coffee served by women tastes the best.” Sung Joon-sik indifferently warns Park Jong-sik that “these days your comments can get you in trouble.” However, Park Jong-sik doesn’t head his warning and instead asks Shin Da-in to make him another coffee for him, which she does even though the other women and her look very uncomfortable. Park Jong-sik then leers at Shin Da-in while her back is turned and makes a comment to Sung Joon-sik about her body. When the women turn and look at him offended, Park Jong-shik picks up a magazine with a picture of a car and says that he was talking about the car. With this excuse the women can’t directly tell them to stop. This encourages Park Jong-shik to continue making various innuendos about Shin Da-in, in context of the cars from the magazine. Sung Joon-sik finds this amusing and begins to chuckle; this incites Park Jong-shik and he gains more confidence and becoming more brazen with his words. At the time they got away with it by not overtly referencing the women in the room, however when Park Jong-sik gets confronted by his boss Oh Sang-shik for the incident he simply brushes his reprimand off— by laughing.

Sexual comments or jokes, like the ones I mentioned above, are some of the most common forms of ‘sexual harassment’ in the Korean workplace. Women are also more likely to take a passive resolution to this form of discrimination, by simply “suppress[ing] their anger and ke[eping] silent.” However, I think this kind of ‘harassment’ needs a more active response. I think the best solution was summed up by one of the women, Lee Sung-eun interviewed in his article that:“If I respond to sexual jokes lightly, they think it is funny. Therefore, we need to respond to their behaviour directly. After all, I need to inform them that I do not want to listen to their jokes. If we hush up the action, we fall into a trap ourselves.” It is only when women stand up for themselves, like the current #metoo movement going on in Korea that things change. Because the truth is ‘sexual harassment’ is no joke. And I think Korean Society is starting to learn this. But in order to do this their needs to be a growth in the number of women in high positioning jobs like managerial positions, company boards, and parliament. As without representation, women are left vulnerable to old patriarchal expectations and suffer being taken advantage of by fellow male employees in higher positions.

Bibliography:

Bicker, Laura. “#MeToo movement takes hold in South Korea.”BBC News, March 26, 2018, World (Asia) Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43534074

Chung, Catherine. “Middle school teacher probed over sexual violence claims.”The Korea Herald, March 14, 2018, National Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180314000897

Chung-un, Cho. “#MeToo spreads to business sphere, partially.” The Korea Herald, March 6, 2018, Business Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180306000703

Doo, Rumy. “Korea’s Gender Ministry to monitor news reports on #MeToo.”The Korea Herald, March 28, 2018, National Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180328000628

“[Foreign Correspondents] Ep.76 – South Korea’s #MeToo Movement _ Full Episode.” hosted by Seo Misorang, featuring Elise Hu and Frank Smith and Koichi Yonemura, published on March 5, 2018, ARIRANG TV, Youtube. [25:12 min total] (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb9vy8No–A

“Former South Korea presidential hopeful Ahn Hee Jung denies rape.”The Straits Times, March 19, 2018, East Asia Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

He-rim, Jo. “Wife of Lawmaker accused of sexual misconduct under fire for supporting husband.”The Korea Herald, March 11, 2018, National Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180311000158

Hyun-bin, Kim. “Gov’t to conduct ‘Me Too’ survey in colleges nationwide.”The Korea Times, March 23, 2018, Education Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2018/03/181_246113.html

Jumabhoy, Fatim and Lee, Lauren. “South Korea: Tough New Sexual Harassment Amendments Enacted.” HRnews, June 1, 2018, Employment Law section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

Kwang Taek, Lee. “The Legal Institution of Korea for Prevention of Sexual Harassment at Work as a Sex Discrimination.” Kookmin Law Review 25, no. 3 (2013): 271-308.

Min-ho, Jung. “UN urges Korea to protect #MeToo accusers.”The Korea Times, March 13, 2018, Politics Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2018/03/356_245548.html

Misaeng 미생 (also known as: 아직 살아 있지 못한 자 “An Incomplete Life”). Directed by Kim Won-seok. 2014; South Korea: Number 3 Pictures, TV Drama. Netflix.

Privey, Alice. “#MeToo: South Korea’s Social Revolution.”Institute for Security & Development Policy, June 20, 2018. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://isdp.eu/metoo-south-koreas-social-revolution/

Rahn, Kim. “Ex-assembly speaker accused of sexually harassing caddie,”The Korea Times, September 14, 2014, National Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2014/09/116_164532.html

R.H., Lee, “Korea said #MeToo. Here’s how it’s different.,”The Dissolve, April 17, 2018, Gender, Society Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://thedissolve.kr/korea-said-metoo-heres-how-its-different/?ckattempt=2

Sang-hun, Chloe. “A Director’s Apology Adds Momentum to South Korea’s #MeToo Movement.”The New York Times, February 19, 2018, Asia-Pacific Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/19/world/asia/south-korea-metoo-lee-youan-taek.html

Sung-Eun, Lee. “Practical Strategies Against Sexual Harassment in Korea.”Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 10, no. 4 (2004): 7-30.

Tong-hyung, Kim. “‘Yoon Chang-jung: the aide who grabbed me.’”The Korea Times, May 14, 2013, Culture Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2013/05/135_135669.html

The Data Team. “The best and worst places to be a working woman.”The Economist, March 8, 2017, Daily Chart Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/03/08/the-best-and-worst-places-to-be-a-working-woman

Yonhap. “As ‘Me Too’ sweeps Korea, conspicuous silence within K-pop.” The Korea Herald, March 7, 2018, Life & Style Section. (Accessed: June 28, 2018)