As an American living in Canada for the first time, I knew nothing about Canadian history when I first arrived. Then, after only a few weeks upon my arrival, I learned about the residential schools and the TRC. Basically, this was the first history I had ever learned about Canada, and it really amazes me that out of all the Canadian historical facts that could be drilled into my brain–first 10 prime ministers, the foundation of Canada, the Canadian national anthem (which I still need to learn!)—I learned about a very important part of history that Canada is not proud of, but is still impressively taking a huge effort to reconcile and apologize for. And what makes this even more shocking to me is that before moving here, the idea of residential schools was completely foreign to me. I had no idea that they had even existed in the U.S. as well. The topic of residential schools and the assimilation of Native Americans was never brought up in school or in the news. I had no idea it was even part of my own homeland’s history. And this, honestly, makes me rather angry. How could such a terrible event that affected so many people’s lives, never be mentioned? Why do I have to come to Canada to hear about it? I am proud of the Canadian government and citizens to rightly acknowledge this awful, dark historical event and truly reconcile and apologize for it. Also, the step UBC took in cancelling classes for the day shows how important this event is and how committed everyone is to true reconciliation. However, my next question is, what is the government doing to make sure something like that never happens again? This is also an important part of reconciliation.

While attending the TRC events, I became more and more shocked by what I saw, heard and read. At one event I went to in the UBC Longhouse, they were showing live recordings of the people speaking at the PNE. One question that Caroline Wong asked which really struck me was, “What is the price for loss of land, loss of family, loss of tradition?” It made me realize, this kind of damage that was done was the worst kind. It cannot be replaced, it cannot be brought back to exactly the way it was before. Nothing can be given as a “make-up.” These deep traditions that the First Nation people have been passing on for generations were wiped away and smothered by the beliefs of the white.

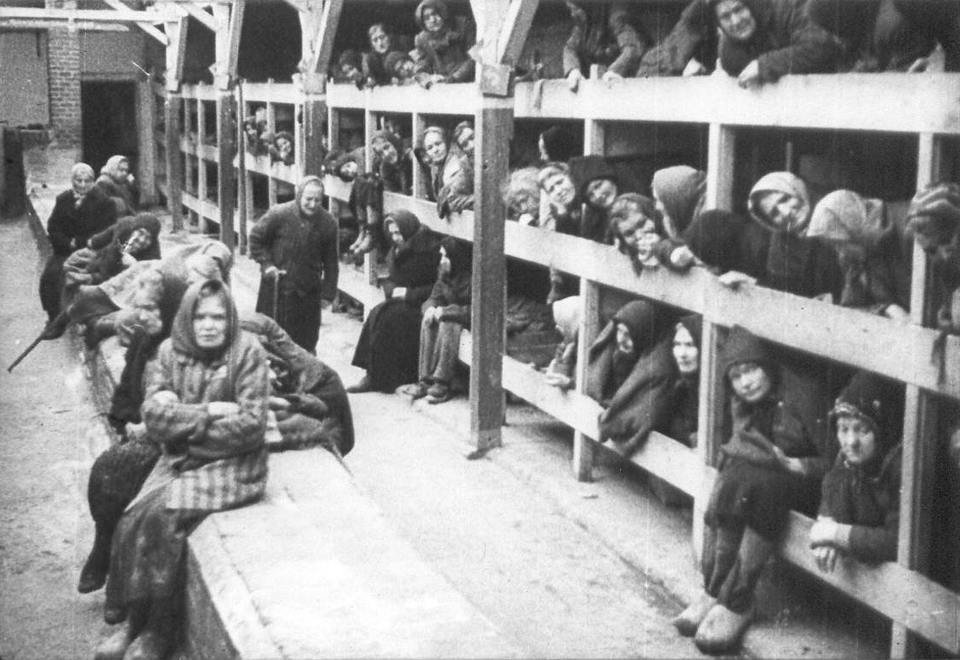

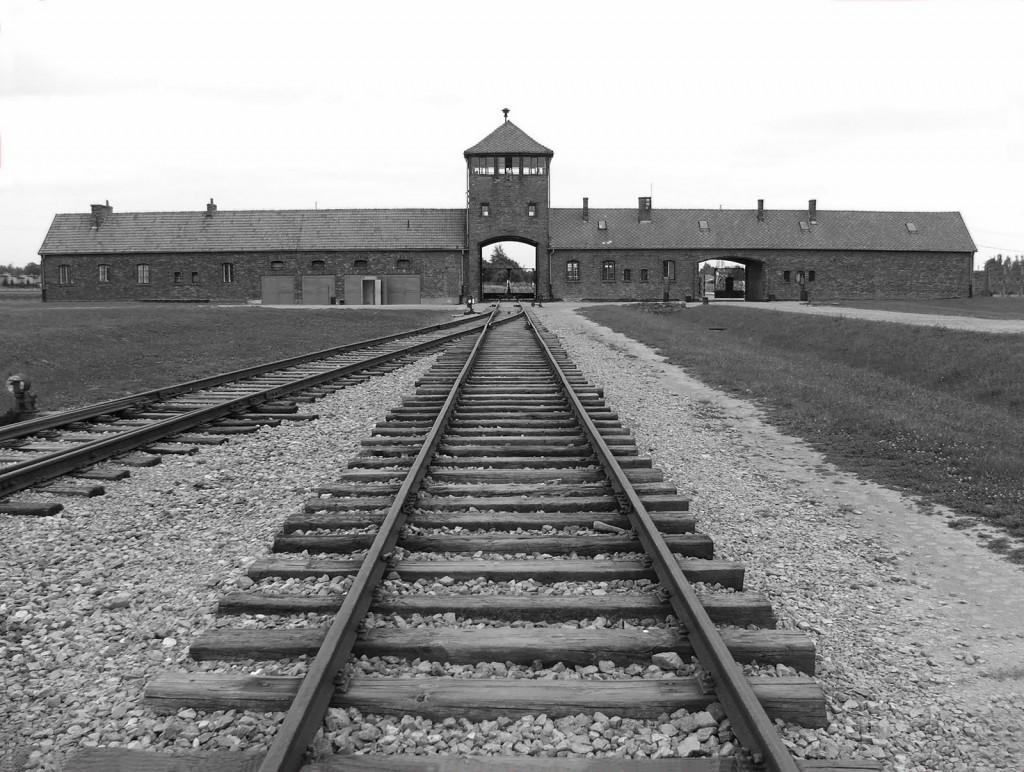

The man (I believe his name was Daniel Richmond) speaking about reconciliation and the Holocaust, discussed how reconciliation is not only important in order to show that the wrong-doing is acknowledged and apologize for it, but also to make sure something like the residential schools never happens again. People need to understand exactly what happened in order to put a system into place which prevents it from reoccurring. Unfortunately, after doing some research on the current aboriginal human-rights record in Canada, I found that the Canadian government has not been taking as many steps towards the improvement of First Nations organizations and the treatment of aboriginal people as they should be. The government has recently made large budget cuts for First Nation organizations (http://akagallery.org/cathy-busby-budget-cuts-2012-from-every-line-every-other-line/), and in the past few years violence towards aboriginal women has increased. For example, a report came out this past February about police officers sexually abusing young aboriginal girls and women. Check out the article here: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/rcmp-accused-of-rape-in-report-on-b-c-aboriginal-women-1.1305824

In addition, just one day after the official TRC event at the PNE, a report was released that after the UN Human Rights Council asked the Canadian government to perform a “comprehensive national review to end violence against aboriginal women,” the Canadian envoy refused. Check out the full article here: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/canada-nixes-un-review-of-violence-on-aboriginal-women-1.1860828

These examples show that even though Canada is going through the steps of reconciling, the country is not learning from its mistakes. It is not taking steps to prevent the re-occurrence of those terrible events which caused thousands of First Nation people’s lives to be ruined forever.

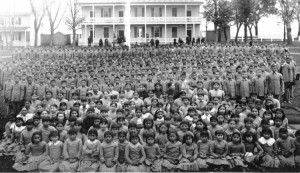

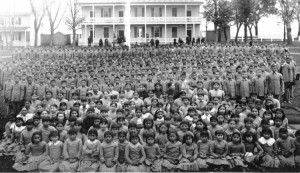

The emotions I felt during my visit to the exhibition Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools at the Belkin Gallery are difficult to describe. I felt as if for every artwork I saw, I sensed a different kind of emotion. All of these emotions put together are a good representation of how the entire residential school situation makes me feel. For example, the large artwork The Lesson made me depressed and disturbed by the very cruel layout of the chairs and desks, and how they were all chained to each other and looked identical, with hooks sticking out of the apples. It made it seem like a prison where the children would be tortured and brain-washed into one giant identical army of zombies. The children were not taught religion, they were beat into it. They were taught that their traditional beliefs were evil and their ways were work of a devil. The “killing of the Indian in the child” was a strong theme of the artwork, and something that really got to my deepest emotions. I find it extremely sad when such rich tradition is lost and small, innocent children are taught that their families basically work for the devil. Below is a picture of what the artwork The Lesson reminds me of—hundreds of children being brain-washed into a monolithic group, with their spirits broken and living in fear day in and day out.

http://kolonialq.wordpress.com/2013/01/27/idle-no-more-meets-invasion-day-australia/

On the blackboard for Memory Wall, there were stories written of aboriginal children being refused treatment when they were sick or injured. After my research on the current treatment of many aboriginal people today, it doesn’t seem like they are being treated much better. They are still treated unequally, and this is something that really disappoints me, especially considering that the nation has put so much effort into apology and reconciliation. Leaders and decision-makers need to see that apology is only one small part of reconciliation. The other part is making new systems and laws to keep the issue from reoccurring.

Finally, Gina Laing’s paintings brought tears to my eyes. I feel that her artwork was so heart wrenching because of how personal it was. The viewer could truly see into Gina and how her experiences affected her internally. I remember in one of the descriptions she explains how she developed “a sense of disembodiment.” This again goes back to the idea of the children becoming one giant homogenous group, where none of them have any sense of who they are or where they come from anymore. That is the worst position for a child to be in, and that is why so many of them grew up into lost individuals with no path in life and addictions to drugs and alcohol.

As it did for most people, the TRC and the events really had a strong emotional effect on me. I am so happy that this nation I am now a resident of is strong enough to admit its wrong doings and take the steps to properly reconcile and that so many people support this. Now, the Canadian leaders need to put more effort into putting systems into place which will prevent residential schools or anything like them to ever happen again, and to work on ending the violence inflicted on aboriginal people.