(This is gonna be a bilingual post !)

(This is gonna be a bilingual post !)

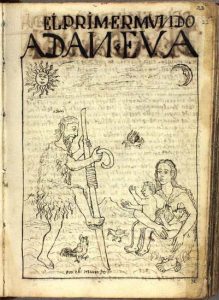

We’ve talked a lot about indigeneity and how we make/unmake it, but we haven’t talked much about the gray area that exists between those two extremes of indigenous and “not”. According to the RAE, “mestizo” means “Born of a father and mother of different race, especially of white man and Indian, or of Indian and white woman” and/or “Coming from the mixture of different cultures”. It differs from a Creole who is of European heritage on both sides, and born in colonial territory. But, as we’ve been uncovering in our course, the indigenous and thus mestizo identity is more complex than the content of blood. Although the meaning of the word mestizo has changed over the years, it has always been a “socially and historically constructed identity” (Martinez-Echazabal). In Comentarios Reales, It is not so clear what relationship El Inca has with his cultural heritage as a mestizo.

Desde el Proemio, hay una ambigüedad sobre sus intenciones, él dice que escribió C.R “forzado del amor natural de la patria” (Voces Proemio.8), pero ¿Cuál es su patria? ¿Patria peruana? ¿Patria Inca? Al inicio, parece que identifica con un indigenismo pre-colonial, “Yo nací ocho años después que los españoles ganaron mi tierra” (Voces 1.XIX.19-20) pero el uso mezclado del “Su” y “Nuestro” en referencia a los Inca crea un conflicto entre su origen y su identidad.

Por un lado, Garcilaso identifica con la herencia Incaica “…sabiendo que un indio, hijo de su tierra (Voces 1.XIX.29-30) y parece que se considera culturalmente incaica “con lo cuales me crié y comunique hasta los veinte años” (Voces 1.XIX.5-6). Especialmente, Garcilaso aprovecha de sus relaciones indígenas para justificar su escritura, “…para que se vea que no finjo ficciones en favor de mis parientes [los Inca]” (Voces 1.XIX.51-52). Aún más, hay un esfuerzo de poner distancia a su herencia europea como “allá los españoles” (Voces 1.XV.25). Parece que no considera a los españoles como parientes cercanos.

Pero en contraste, él también emplea el “Su” para distanciarse de los sellos culturales incaicos, “Me contaban sus historias… larga noticia de sus leyes…como procedían sus reyes… trataban a sus vasallos… su idolatría… sus ritos…sus fiestas… sus abusos… sus agüeros…sus sacrificios…su república” (Voces 1.XIX.8-15). El uso repetitivo del “su” parece contrario a la previa insistencia de su raíces y relaciones como los indígenas incas.

Para ponerlo más complejo, a veces Garcilaso usa los artículos de manera mezclada. En el capítulo XV, el uso del “Su” (vuestro) y el “nosotros” (nuestro) está muy presente. En el mismo pensamiento, aparece el uso de los dos sujetos,

“Inca, tío, pues no hay escritura entre vosotros, que es la guarda la memoria de las cosas pasadas, ¿Qué noticias tenéis del origen y principios de nuestros reyes?” (Voces 1.XV.23-24)

“Empero vosotros que carecéis de ellos, ¿Qué memorias tenéis de vuestras antiguallas? ¿Quién fue el primero de vuestros Incas?… ¿Qué origen tuvieron nuestras hazañas? (ibid. 28-31)

From this discontinuity, Inca Garcilaso shows the complexity of mestizaje identity. The conflict of biraciality means that mestizaje does not fit into any pre-established group. The creation of a “Nuevo nosotros” is fundamental to mestizo identity, His identity as a mestizo is composite of his indigenous heritage, and also his Creole environment. The two cannot be separated without destroying the novel identity and trying to celebrate one while ignoring the other is contrary to their physical existence. Most people we meet and interact with will have some mix of pre-Hispanic and European ancestry. Peruvian culture as we know it now is a mix of pre-Hispanic and European/Western culture.

Does the centering of mestizaje constitute a Making or an unmaking of indigineity in the way which we have been studying it?

————————————————————————————

Quotes and analysis adapted from “El desarrollo del mestizaje en Perú por El Inca y José María Arguedas”, Morgan Cooper 2023.

Voces de Hispanoamérica: antología literaria. Eds. Malva E. Filer y Raquel Chang-Rodríguez. 5ª ed. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017. 66-67.

Martinez-Echazabal, Lourdes. “Mestizaje and the Discourse of National/Cultural Identity in Latin America, 1845-1959.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 25, no. 3, 1998, pp. 21–42. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2634165.