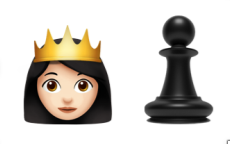

For Task 6, the challenge was to use emojis to convey the title and plot of the last TV show that I watched.

See if you can crack the emoji code!

The Title:

The Plot:

As I began this task, I knew I wanted to select a TV show that resonated with me. I also knew that an exact word-to-emoji translation of a keyword from the show would not be available. I was confident that I would find a pictorial rendering that would convey the concept, and I was correct. However, this would not be the final hurdle I would encounter during this task.

Written communication is a mode of preference for me. My love of writing and words made this task particularly uncomfortable. The restriction to not use any words, only pictures, made me feel disadvantaged in the realm of communication, a realm where I generally feel at home. Kress (2005) understands my hesitance: “The response is understandable given the long domination in the West of writing as the culturally most valued form of representation…” (p. 5.) If the written word’s value is diminished, what would happen to the sense of self-worth generated by winning spelling bees and writing contests in my younger years? Would the appreciation of technology that led me to this graduate program ultimately depreciate my writing abilities? In a review of interactive verbal text, Kress (2005) gives me cause for concern, suggesting that the technology can “…subordinate the text, as comic books or so-called “graphical novels” do in print…further diminish the status of any text that appears in this electronic environment” (p. 76.) Diminished status??!! Bring on the panic.

Bolter (2001) provides further context for my fears regarding my “emojiing” skills, noting that “…verbal text has usually contained and constrained the images on the printed page” (p. 47). The tables were turned for this task, with emojis containing and constraining my capacity to communicate.

Despite the aforementioned trepidation, I found the task of “emojiing” the title of my TV show selection to be easy enough. It helped that I had no expectation of finding a direct translation for all of the words in the title. I suspect that the rest of the experience would have been much simpler if I had continued to let go of the expectation of finding an emoji to fit each word. Instead, I created a word-based narrative in my mind, using words to describe the sequence of events. Kress (2005) suggests that this is part of the meaning-making process: “Time and sequence in time provide the organizing principle for making meaning. Sequence is used to make meaning; being first has the potential to mean something other than being second or being last” (Kress, 2005, p. 12.) My preference to use language rather than pictures is part of a common belief that “…meaning in language is clear and reliable by contrast, with image for instance, which, in that same commonsense, is not solid or clear” (Kress, 2005, p. 8.)

As I searched for emoji equivalents for words in my sequential narrative, I realized that this approach would not work. Most emojis did not clearly capture the meaning of the word I was trying to convey. I feared that they would create more confusion than understanding, with multiple meanings being derived from the image. As Bolter (2001) writes, “…the picture elements extend over a broad range of verbal meanings: each element means too much rather than too little” (p. 59.) Kress (2005) also seems to understand my struggle: “Sometimes, particularly when the picture text is a narrative, the elements seem to aim for the specificity of language” (p. 63.)

It was time for something different.

It was time for something different.

This task was not about writing and communicating in the usual way. It was about re-designing communication, with the possibility of shaping it into something better.

“Words being nearly empty of meaning need filling with the hearer and/or reader’s meaning. Semiotically, words are signifiers, not signs: When they are used in representation they become signs—of the maker and of the receiver and/or remaker” (Kress, 2005, p. 15.)

I was drawn to Kress’ (2005) notion of collaboration between maker, receiver and/or remaker. The co-creation of communication is far more compelling (and realistic) than trying to control the message and its meaning as it is received.

Kress (2005) proposes the idea of “reading as design;” a concept where “…out of material presented (by an author, designer, and/or design-team?) on a page, the reader designs a coherent complex sign that corresponds to the needs that she or he has. That is a profoundly different notion of reading than that of decoding…” (p. 17.)

I’d like to think that it was my embracing of “reading as design” that allowed me to let go of the attachment to words that plagued the onset of this task; that it rekindled my trust in the meaning-making process of my emoji story readers.

In truth, I just had to get this assignment done. I really had no choice but to let go of trying to represent words with images. I had to “let the pictures do the talking.”

As a coaching professional who supports empowerment through personal meaning-making, I want to encourage multi-modal learning and expression. To this end, I appreciate how Kress’ (2005) concept of “reading as design” honours the role of human agency in communication:

“Agency of the individual who has a social history, a present social location, an understanding of the potentials of the resources for communication, and who acts transformationally on the resources environment and, thereby, on self are requirements of communication. Where critique unsettled, design shapes, or has the potential always to shape. It makes individual action central, though always in a field saturated with the past work of others and the present existence of power” (p. 20.)

When I let go of the focus on words, I initiated my own meaning-making process. I thought about the overall messages of the plot and the emotional journey created by the story. Reflecting on the emotional experience of key events – rather than a verbatim re-telling of the story – made it much easier for me to identify emojis that could convey the plot.

Transitioning to “symbolic storytelling” became more comfortable as I worked with what I had, rather than trying to force the emoji language to fit my word=symbol language. In my mind, words became replaced by images of a memorable moment from the show, and I would then search for words associated with my experience of that moment. This was far more productive than previous approach of trying to find images to fit the sequential order of “this happened” then “that happened,” etc. The steps of 1) recalling a memorable moment, then 2) recalling its emotional experience, then 3) conjuring words associated with the emotional experience, and 4) using those words to find symbols to tell the story, offered surprising flexibility. I still ended up with the process I knew – word=symbol – but the path to get there was very different.

At the beginning of this blog entry, I invited you to see if you could “crack the emoji code.” As noted earlier, Kress (2005) suggests that by allowing reading to be a meaning-making process, a process that “corresponds to the needs” of the reader, we can offer “…a profoundly different notion of reading than that of decoding…” (p. 17.) I encourage you to find your own meaning in my emoji story; a meaning that corresponds to your needs. Perhaps your need is to decode my emoji story and identify the TV show that inspired my collection of pictures. Perhaps your need is to let your imagination wander and see what it creates from the rows of images. You have the agency to make meaning in any way you choose.

(If you are curious about the TV show behind my emoji story, here is a link to its trailer.)

References:

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). The breakout of the visual. In Writing space: computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Routledge. (pp.47-76).

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and Learning. Computers and Composition 22(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004