To Write or to Type?

“When handwriting, there is simultaneous, continuous and concurrent visual, motor and kinesthetic feedback providing the brain with spatiotemporally contingent information – the movement (making strokes, lines, dots and curves) of the writing hand entails online feedback to the brain about the visual shape of the specific letter presently being produced. When keyboard writing, locating and tapping keys on the keyboard do not entail any such information to the brain. Behavioral as well as neuroimaging studies provide evidence of the importance of such feedback, indicating that the sensory and motor processes of handwriting – but not keyboard writing – contribute to the subsequent visual representation and recall of the letter. The handwritten letter is, literally, an “imprint of action” in a sense that keyboard writing is not” (Mangen & Balsvik, 2016, p. 102.)

“To write or to type?” is the question for this week’s task. In considering this question, I have discovered that while I am equally a hand-writer and typist in terms of “total hours spent,” my writing process typically starts with a pen and ends with a keyboard. With pen in hand, I feel more connected to the unique, personal perspective that drives the planning and execution of a final, typed product. While completing this assignment, I discovered that my preferred process is not one of universal preference, and that my preference may be as much a reflection of my generation as the effectiveness of either tool.

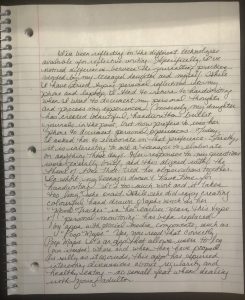

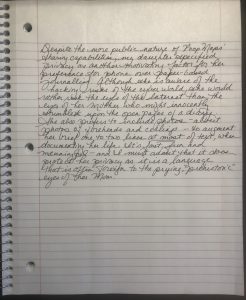

Given that this task asked me to start with a piece of handwritten work, I found the process to be easy and enjoyable. I chose to focus on journaling, the process that provides a “paper mirror” (Hibsch & Mason, 2020). I first discussed the topic of personal journaling via handwriting or typing with my daughter, and then reflected on the topic through writing. The resulting work follows below (please click the images to enlarge.)

Had I been asked to start the task with typing and finish in handwriting, I suspect it would have been more challenging; like writing in a foreign language with my left hand (I am right-handed.) It just wouldn’t feel right.

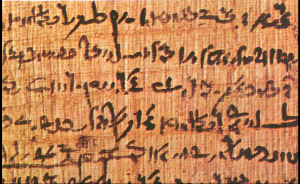

The “feeling” experience, both at a physical and emotional level, is what I consider to be the most significant difference between writing and typing. I like the physical feeling of a pen in my hand. To be fair, I also like the smooth responsiveness of my Macbook keyboard. It offers a vastly more pleasurable typing experience than that of the Microsoft Surface Pro keyboard I use for work. However, neither keyboard feels like a direct extension of me in the way that my pen does. Unlike the laboriously pained writings of scriptorium-bound, medieval monks as described in Brad Harris’ “The Printed Book: Opening the Floodgates of Knowledge,”

I am fortunate to enjoy the light friction of my pen against the paper. I do not have to contend with errors made after a quill has faltered along the jagged edge of a papyrus stem; errors that might require me to throw away the efforts of countless hours as I resume the writing process again from the beginning.

The tactile experience of handwriting (or keyboarding, for that matter) may contribute to thinking processes through “embodied cognition.” Embodied cognition suggests that “…human cognition is not limited to internal processes within the brain, but that cognitive processing is fundamentally dependent on the body, postures and bodily movement in engagement with the physical environment in which we live (Mangen & Balsvik, 2016, p. 100.) Further, embodied cognition recognizes that our cognitive processes are “…based on reinstatements of external (perception) and internal states (proprioception) as well as bodily actions that produce simulations of previous experiences” (Mangen & Balsvik, 2016, p. 100.)

The proprioception element of embodied cognition alludes to the connection between the physical and emotional experience of handwriting; an experience that I view as distinct from typing. According to Sacks (1990) “…some refer to proprioception as the ‘sixth sense’ that allows us to experience our bodies as our own” (Sacks, 1990, p. 43, cited in Briggs 2012, p. 214). In addition, Briggs (2012) writes, “…proprioception is not only physiological. Our thought flow also accompanies us – and is distinctly our own. Reflecting our own individual ideas, concerns, fantasies, questions, grievances, remembrances, our thinking is not random. (Briggs 2012, p. 215). In my experience, handwriting is more likely than typing to help me to process experiences, generate creativity and access different “types of knowing,” such as intuition. When I use handwriting rather than a keyboard in a journaling capacity, I feel more connected to my thoughts and feelings. Further, it is sometimes easier to liberate my handwritten thoughts from the heightened expectations placed on myself for my typed work, as typing often leads to disseminating. The fear of others’ judgements (and those of my own inner critic) can stymie writing of any sort, whether handwritten or typed.

When avoiding mistakes in typewritten compositions, I find that the flow of thought can be interrupted by keyboarding errors and the ease at which edits can be made. Writing and editing seem to happen simultaneously but in a choppy, staccato manner. When handwriting, I edit more in my mind. “Mind editing” likely slowed the process for this week’s task and might have led to more deliberate thought and word choices. I made one error in this writing exercise that I had to cross out with an “X.” As the error happened on page 2, this was especially disappointing; I almost made it through the task unblemished! If it had been a typewritten exercise, the reader would have been none the wiser. But if it were a typewritten exercise, its content would have been quite different. I know this from the moments where I wondered how an online thesaurus or Google search could contribute to my musings. If I had been able to access the tools of my keyboard, I would have written a different composition.

The journaling experiences of my digital-native-daughter suggest different preferences from mine. While her earlier journaling days included artistic and graphic depictions of her life, such as the Mood Tracker example below, she now prefers to document her life through apps that involve just a click here, a photo there, a brief word or two, and maybe a share with a friend. (If you didn’t read the handwritten component of this week’s task above, you might want to read it to understand more about the “Poop Map” app images below.)

As a teenager, my daughter says that she doesn’t have time for handwriting as it takes much longer than typing. She also considers her mechanized writing to be more private. At this stage in her life, she doesn’t report any loss of therapeutic benefit when journaling via iPhone instead of a leather-bound journal. In fact, her digital journaling includes more images than she would normally have in a paper journal, and these images can sometimes convey more than words. As we move into a digital age, my preference for handwriting may be based more in the comfort of the familiar than in the superiority of the mode of expression. Pujolà (2010) notes that “digital environments such as blogs, infographics or e-portfolios allow for different possibilities in terms of facilitating metacognitive reflections beyond the written word” (Pujolà, 2010, cited in Birello & Pujolà, 2020, p. 535). Blogging in particular has been shown to provide “…all of the same opportunities as journaling, including the introspection of values and actions, and the reflection of life circumstances” (Hibsch & Mason, 2020, p.3).

While blogging compromises the privacy that is a priority for my teenager, it can still yield the benefits of journaling in terms of fostering connecting with one’s authentic self. In fact, Hibsch & Mason (2020) purport that “…bloggers are likely to present a true representation of the self online” (p. 4.)

As writing has evolved from using the surface of animal hides to the surface of an electronic tablet, I might need to evolve as well. Or, perhaps we can consider ways to merge the best of both worlds, such as University College London’s software that allows a writer to see their own handwriting when they type!

References:

Birello, M., & Pujola Font, J. T. (2020). The affordances of images in digital reflective writing: An analysis of preservice teachers’ blog posts. Reflective Practice, 21(4), 534-551. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1781609

Briggs, K.A. (2012). Performing Dissident Thinking through Writing: Using the Proprioceptive Question to Break Out of the Classroom. In Faulkner, J. (Eds.)Disrupting Pedagogies in the Knowledge Society: Countering Conservative Norms with Creative Approaches (pp. 212-224). IGI Global. http://doi:10.4018/978-1-61350-495-6.ch016

Hibsch, A.N., & Mason, S.E. (2020). The new age of creative expression: The effect of blogging on emotional well-being. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 1-11.

Mangen, A., & Balsvik, L. (2016). Pen or keyboard in beginning writing instruction? Some perspectives from embodied cognition. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 5(3), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2016.06.003

Meipsy Shackleford

March 7, 2021 — 5:09 pm

Hi Kirsten: Thank you for your wonderful description of this task. You really captured not only your own experiences but also your daughter’s perspective as well along with the course readings. I like how you referenced that your teenage daughter, “Doesn’t have time for handwriting as it takes much longer than typing,” as that seems to be a very real response for many these days with our access to technology. From a different perspective, my daughter who is nine, absolutely loves to handwrite and keep little journals. Her exposure to typing on a computer however is still limited, so perhaps as she learns more about blogging and having more practice beyond the paper pencil, she too will agree with you daughter.

KIRSTENMCKINNON

March 7, 2021 — 6:30 pm

Hi Meipsy! Thank you for your comments. I am interested to hear about your daughter’s experience with handwriting. You reminded me that my daughter kept many handwritten journals in the “before time” (before she had a phone.) I wonder how much of her current preference is tied to her experience of time. I imagine that a 9 year old may not feel the same time pressures of a 17 year old. I appreciate how you have sparked continued reflection on this. Thanks!