Eight weeks ago I invited readers to envision a Canada that works for all generations. The conversation gained momentum thanks to readers across the country.

Much of the feedback has been positive, suggesting the columns have helped to name what many in Generation Squeeze feel. But there has also been criticism.

As an academic, I welcome critique. It can signal where one may need to adjust thinking. I therefore wish to carry on the conversation this week by engaging directly with some of the concerns readers have shared.

Andrew Wister, SFU Professor of Gerontology, succinctly captured a common set of criticisms. In an Oct 25 Op Ed, he wrote that “Pitting young families against older generation isn’t helpful.” He worries that my columns blame Boomers and seniors for the squeeze on those that follow.

Professor Wister is correct that generational conflict is not helpful. But let’s be clear about its origins.

The potential for conflict exists because social and economic trends over the last four decades have worked to increase average incomes and wealth for those approaching retirement, while squeezing the time, income and services for many in the following generations who now raise young kids (see 10 provincial Family Policy Reports, Does Canada Work for All Generations?). If there is a tension, it is because there has been a slow seismic shift in the Canadian environment, and we didn’t change with it. We abandoned our beaver logic, neglecting to build policy in response to the declining standard of living for Generation Squeeze..

Merely talking about data to illuminate intergenerational pressures need not create conflict. Quite the opposite. Until we showcase the information, Canadians have little impetus to make change.

The discussion of “blame” to which Professor Wister refers has arisen several times in response to my columns (see also the October 24 Op Ed from Robert Ages of Delta). Blame is not a game for me. I aim to be very careful about this issue, generally emphasizing personal responsibility.

For instance, I have argued that much responsibility for the bad intergenerational deal rests with Gen X-it – adults in their prime child rearing years who are less likely to use their political voice, especially during elections.  At the same time, I compliment the Boomer generation on their higher voter turnout, noticing that political parties respond accordingly when developing platforms. And I observe that many of today’s older seniors – the parents of Boomers – were among our country’s greatest policy builders, who simultaneously paid down government debts from WWII.

At the same time, I compliment the Boomer generation on their higher voter turnout, noticing that political parties respond accordingly when developing platforms. And I observe that many of today’s older seniors – the parents of Boomers – were among our country’s greatest policy builders, who simultaneously paid down government debts from WWII.

More generally, I have directed much blame away from politicians to focus on all of us as Canadians, as citizens. We have chosen not to prioritize social policy innovation in support of Generation Squeeze. As a result, it is challenging for political leaders to campaign for what the electorate does not call.

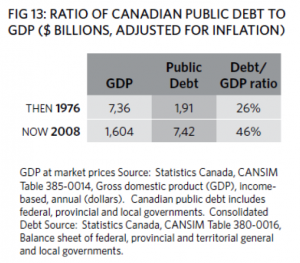

While Boomer blaming is not my interest, a Canadian commitment to personal responsibility does behoove us all to ask and answer the question: Do I leave as much as I use over my lifetime? The fact that Canada’s debt to GDP ratio was 26 per cent in 1976 and 46 per cent as of 2008 (before the recession) sounds some alarm bells. Boomers leave larger public debts than they inherited from the previous generation, even though on average they have stronger financial situations than did near-retirees in the 1970s.  In addition, Canada’s environmental footprint has not improved over Boomer’s adult lives despite growing worries about climate change.

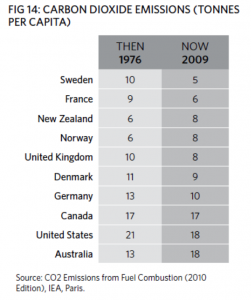

In addition, Canada’s environmental footprint has not improved over Boomer’s adult lives despite growing worries about climate change.

I do not promote ageism by sharing this information, as Kathleen Jamieson of Delta charges in an Op Ed on October 29. Rather I hold out hope for Boomers and their legacy. Because of their influence in our boardrooms, legislatures and as voters, Boomers are essential. They could choose to become proponents of a better deal for their kids’ generation and grandchildren. In so doing, they would restore greater equity between generations, and leave a more solid foundation from which Gen Squeeze can address looming fiscal and environmental debts.

As I speak about generations, I rely on averages to capture important trends. Some have since critiqued that I wrongly portray all Boomers as affluent, and all in Gen Squeeze as worse off. Let me acknowledge emphatically the diversity that exists underneath any average. There is no doubt that some Boomers struggle economically, as many notice when talking with Greeters at Walmart. I salute Angie, Harry O’Neil, Ruth John and many others who insisted on this point, sharing their personal stories by email.

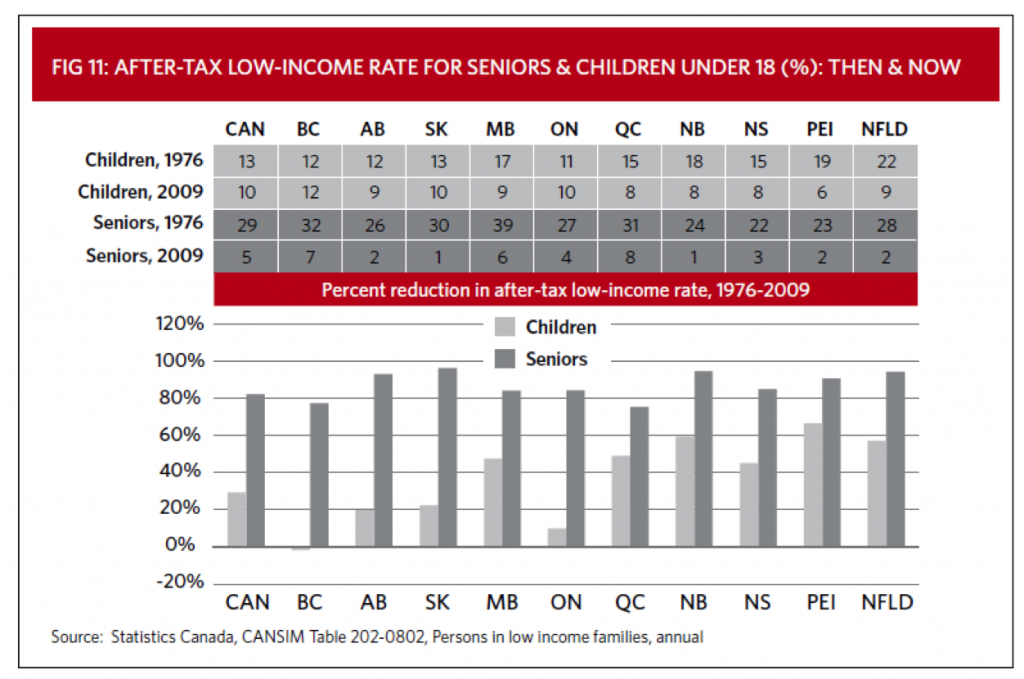

In response, organizations like the United Way point the way forward when they identify isolated seniors AND families with young children as their priority areas for community investment. The fact that Canada wrestled poverty among seniors down from 29 per cent in 1976 to less than 5 per cent today does not give reason to overlook that some seniors still struggle – especially women. Nor does it give reason to ignore the risk of isolation as Canadians live longer, often at great distance from other family.

But addressing these risks can and should occur alongside learning the broader lesson revealed by income trends for seniors. We successfully used policy in the past to adapt our environment for the evolving needs of a generation. Canada can now repeat this achievement for Generation Squeeze.

Notice, the goal is to repeat the success, not replace it. Although policy investments inevitably entail trade-offs, there is no reason to pit seniors or near-retirees against families with young kids, as Professor Wister fears. Canadians are well positioned to choose other trade-offs, whether higher taxes, fewer prisons, re-examining what we include in medical care, or any of a range of alternatives.

However, I make no apologies for initiating a genuine discussion about trade-offs, because they are at the heart of our decisions. Why do Canadians so far resist building policy that will support new moms and dads to have enough time with their young children? Or $10/day child care services? Or employment standards that facilitate balance between work and family? Answer: because we prioritize other goals.

Such trade-offs are no longer consistent with many Canadians’ aspirations to retain the family at the heart of our values. I therefore take my hat off to Professor Wister for expressing his support for the New Deal for Families, and noting correctly that many Scandinavian countries develop policies for the generation raising young kids side-by-side with strong policy for seniors.

It will take many more Canadians to boldly echo the priority Professor Wister so eloquently proclaims before Canada once again works for all generations.

So let’s keep the conversation going. Share your views in the Vancouver Sun, or at paul.kershaw@ubc.ca, blogs.ubc.ca/newdealforfamilies, or twitter.com/#!/newdealfamilies.

On minor comment – empirically, the data shows changing conditions for household income with a worsening situation for those in child raising years. When it comes to causal factors it would appear to me that something other than inter generational deals is at the root. Way back in the early 1970s a shift in labour contracts started that came to be called two-tier agreements in which employers offered to preserve the working conditions and wages for those workers already with full-time employment in return for allowing part-timers with reduced benefits and wages. We now this form of employment in the academic world as sessional or adjunct faculty. My point in mentioning this is that one of the major offensives used by employers to counter rising wages of the exceptional post war two period involved attacking the wages and conditions of new entrants into the work force. Thus, much of the so0-called inter-generational bad deal is, perhaps, more correctly understood as the seismic readjustment of the balance of economic forces back into business/employer’s hands that started in the 1970s and was cemented into place in the 1980s. It is also very useful to note that the post world war II period was very unusual in empirical terms with regard to wages and benefits for the majority of people in Western Europe and North America – so much so that to use those two or three decades as the bench mark is somewhat misleading, even if they are good ones as a goal or objective to focus on as a step in the right direction.