For this task, I used the ‘Dictation’ tool preinstalled on my Windows 10 laptop’. I talked, unscripted, using my computer microphone, about a research article I recently read. Here is the screenshot of the resulting script, followed by my analysis. You can also access the script through this link.

Deviations from conventions of written English

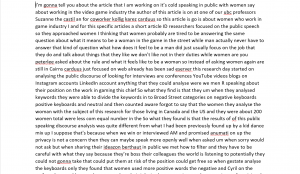

A quick glance over the text was enough to say that there are some rules and standards of written text that this script does not follow. The biggest challenge for comprehending the text is that the ideas are not organized into sentences and paragraphs. Informal vocabulary (e.g. I’m gonna) and filler words (e.g. Umm, like) are other examples of ‘inadequate’ writing.

What is “wrong” in the text? What is “right”?

Writing is a communicative activity (Bauman & Sherzer, 1989), and in my view, this text is not adequately performing the communicative function due to the multiple mistakes and deviations from the norms of written language.

Among the features of the text that are “right” are the grouping of symbols into words divided by single spaces and representing the text in rows from left to right.

Most common “mistakes”

The two most common mistakes that made the whole script very hard to decipher are punctuation and spelling.

The lack of punctuation and not knowing where one idea ends and the next one begins makes the text nearly impossible to understand, even for myself.

Spelling

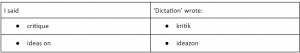

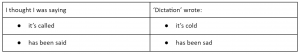

Being an ESL speaker, I speak with an accent. English vowels are the most difficult for me, as the differences in their pronunciation can be very subtle. When analyzing the script, I found a few instances when my wrong pronunciation (that I was unaware of ) was displayed on the computer screen:

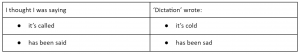

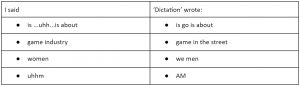

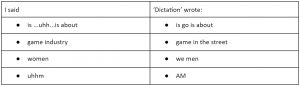

However, my accent aside, I found more instances when the automated script was “simply a record of uttered sounds” (Gnanadesikan, 2011, p. 10), and not a correct encoding of my speech. For example, when I paused, repeated the same word twice, or used a filler, the software encoded the word(s) as something else. For example:

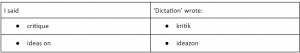

Some words and word linking were written phonetically:

At some points, this phonetic encoding was impossible to decipher even for me, the speaker:

- carduus (times 2!), eserver, peterlee, anumati, berthaut.

A third, less common error, which does not impede understanding to the same extent as spelling and punctuation, is capitalization.

The software only recognized and capitalized

- a few common proper names, such as Suzanne, Canada, US;

- the personal pronoun ‘I’

Other proper names and acronyms were transcribed in lower-case letters.

Lastly, there were also a few words that got both misspelled and erroneously capitalized:

If I had “scripted” the story…

If I had a chance to script this story prior to dictating it to my computer, I would have had time to organize my ideas using a correct chronological progression, and adding headlines, signposts, and punctuation. When dictating my script to the software, I would have pronounced the symbols as words” – e.g. ‘comma’, ‘period’, to ensure better accuracy of encoding my oral text (Gnanadesikan, 2011). Of course, I would have had time to make sure the grammar and vocabulary were more appropriate as well. The script would also have helped me to pronounce words loudly and clearly and avoid using long pauses and fillers, which would result in a much more readable text.

On the other hand, I expect some errors made by the software to stay the same – such as mistakes in capitalization and spelling.

Oral vs. written storytelling

One big difference between oral and written storytelling is that we usually know quite well who our audience is when we talk. In writing, however, our audience can be unknown to us. Furthermore, while oral storytelling disappears as we speak unless we record ourselves, a written story is much more permanent and is able to reach its audience across space and time (Gnanadesikan, 2011).

Another difference is that oral storytelling is not strictly sequential. It is quite common for the speaker to go back in time when information important for the story has been left out. We also repeat words or parts of the sentence, correct ourselves, and use fillers while searching for a suitable word, remembering what happened next, or returning to the story after getting distracted for a moment.

Next, in oral storytelling there are a variety of ways to help the listener follow our ideas as we speak: we use pauses, changes of tone, intonation, and the voice, to emphasize certain information or signal to the listener that we are changing the subject or going back in time. In written storytelling, these technologies are much more limited.

In oral storytelling, just as the speaker can help the audience make sense of the story, the listeners would be more forgiving of his/her pronunciation mistakes. Where software erroneously wrote some of the words I mispronounced as something else, a live audience would be able to understand me much better in context. There is also a possibility of a dialogue and a chance to ask questions or clarify information in live communication. On the other hand, in oral communication, one cannot delete or edit a thought in the way that writing affords it.

Last but not least, we can be emotional as we speak, while a reader has to read between the lines to decipher our feelings from the vocabulary choices, word order, and other writing techniques.

Final thoughts

This writing assignment was material because it required using material technologies – the computer, microphone, pixels, and others that I am unaware of (Haas, 2013). It also resulted in the creation of a visual artifact. I am wondering whether being aware of the fact that my discourse was being moved from an aural to a visual realm (Ong, as cited in Haas, 2013) to be later analyzed by myself, my professor and peers, altered the way I talked.

References

Bauman, R., & Sherzer, J. (Eds.). (1989). Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking (2nd ed., Studies in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611810

Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2011).“The First IT Revolution.” In The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the internet. (Vol. 25). John Wiley & Sons (pp. 1-10).

Haas, C. (2013). “The Technology Question.” In Writing technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy. Routledge. (pp. 3-23).