I told myself I wouldn’t use anyone with the last name ‘Ball’ as an example, but alas…have a look at the two links below as they set the stage for the remainder of the post.

(Bleacher Report: Lonzo Ball Could Be an All-Time Great, but Not Until He Fixes His Jump Shot

A dichotomy exists amongst basketball coaches, one that can be broken down using two famous quotes:

(1) ”If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” – Bert Lance, Director of the Office of Management and Budget, United States Government, January 24th – September 24th, 1977

(2) “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results,” Albert Einstein, no further explanation required

Those coaches who subscribe to the school of Lance believe that each individual has their own particular shooting mechanic that they acquire in their youth. As opposed to making any technical changes to improve percentages, these coaches believe that the answer to shooting woes of any kind is repetion and, well, more repetitions. Both Lavar and Lonzo seem to be fans of this approach, even though his jump shot is most definitely broken.

On the other hand, there are those who like to ‘tinker’. These coaches don’t hesitate to suggest and implement mechanical changes with athletes of any age. They help players improve their shooting form and hopefully, in time, their percentages. Such an approach is controversial with many variables at play not the least of which is managing the ego and expectations of the athlete in question. Despite Einstein’s caution, I believe this to be the less popular approach in modern basketball culture.

As we approached 2017-2018 USports season at MacEwan University, I was presented with a problem. Deonte Doslov-Doctor (his story is very interesting, have a look if you are interested: Deonte’s Story) , who was slated to be our starting shooting guard the following year, wasn’t shooting the ball particularly well. Having lost seven players and four of our top six scorers we needed Deonte to be ready to take on a scoring role…it was a Bert Lance or Albert Einstein decision.

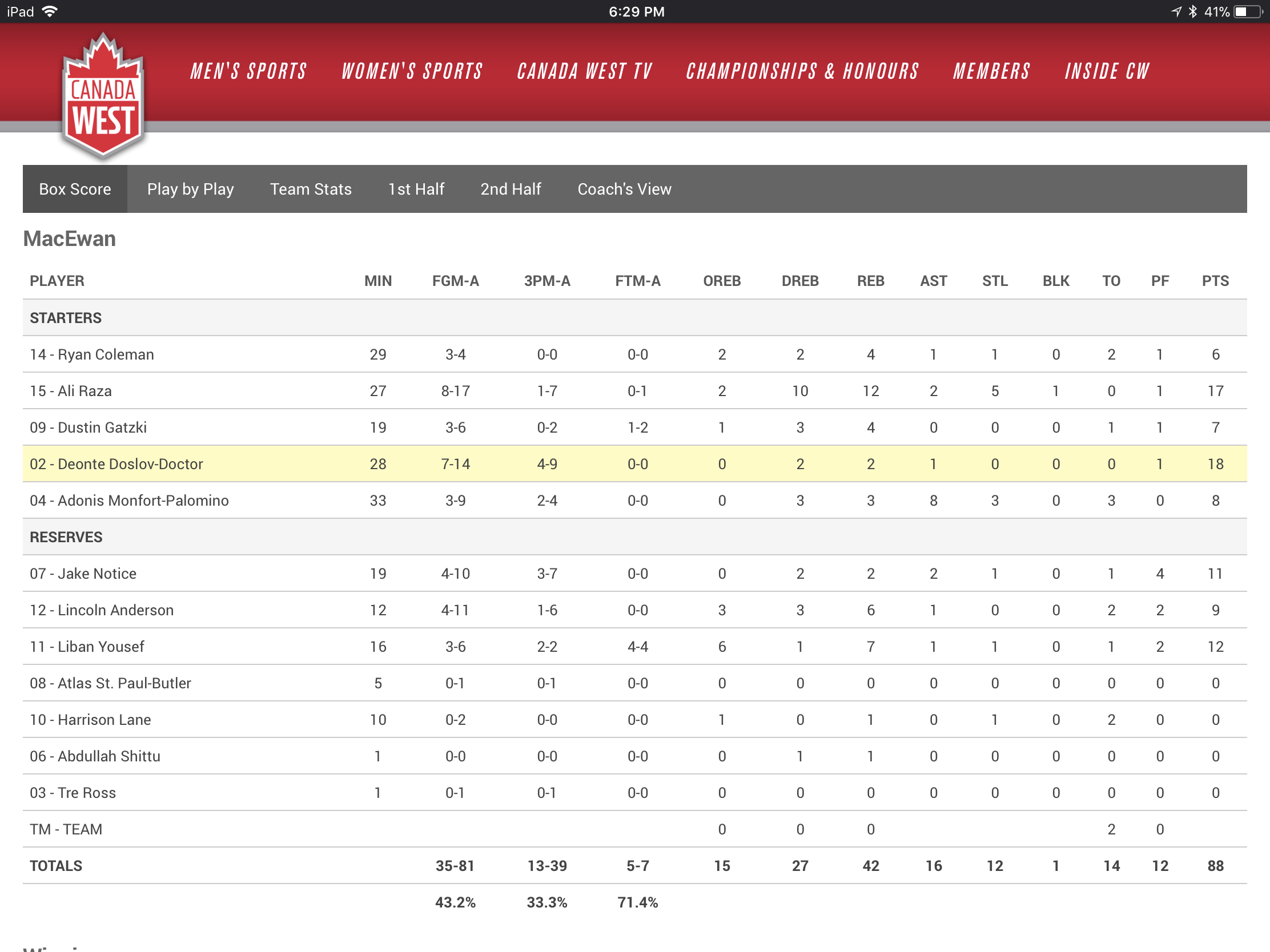

This is what we were working with:

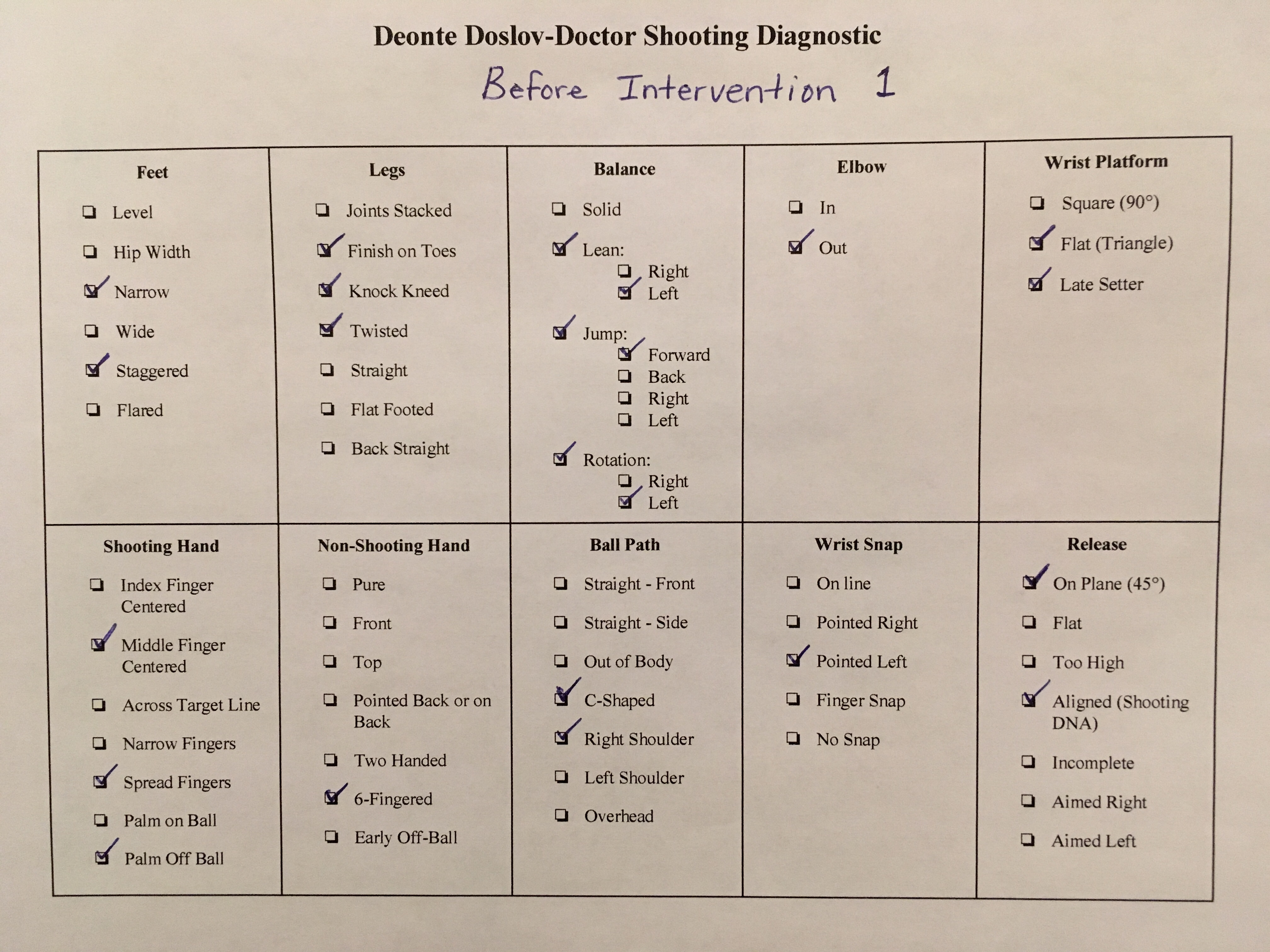

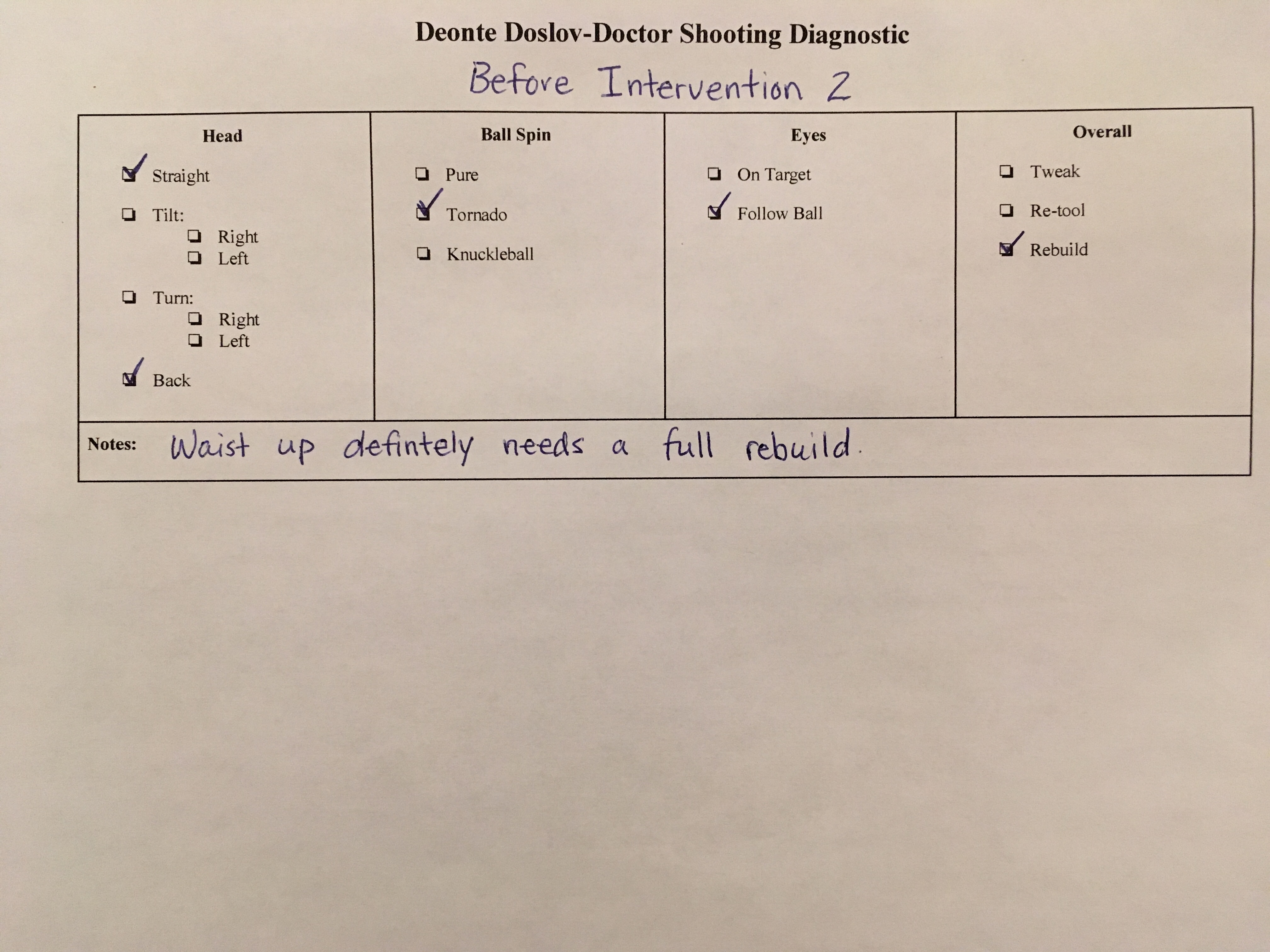

Personally I am a ‘tinkerer’ who subscribes whole heartedly to the Einstein philosophy, thankfully Deonte did too. We started with a shooting mechanic diagnostic tool that I helped create for my good friend Dave Love (check him out on IG, Twitter and Facebook @coachdavelove).

I shared the results of the shooting diagnostic with Deonte and presented him with two options: (1) rep the mechanics you have in order to maximize your shooting with the tools you possess or (2) spend the summer rebuilding your shooting mechanics. The most important part of this step was prepping Deonte for the process. Most athletes expect every alteration to have a positive effect quickly when in reality, at least with mechanical alterations, that couldn’t be further from the truth. I set the stage for Deonte by telling him that this had the potential to take at least a year if not more before he was comfortable with his new mechanics. I warned him that he may get worse before he got better. I warned him that it would require hours of monotonous practice. After all of my warnings, he still wanted to make the changes. So off we went.

We isolated three major aspects of his shot that needed correction: (1) shooting hand placement on the basketball including having a prepared wrist, (2) non-shooting hand placement on the basketball and avoiding any added force from his non-shooting thumb, and (3) the path the ball took from catching at his waist (shooting pocket) to the shooting platform.

We chopped the entire shooting mechanic into smaller parts so as to better address each particular issue. Some of the strategies we used included:

– Isolation drill: stating at the shooting platform and isolating the shooting hand by hovering the non-shooting hand beside the ball. This helps athletes master the shooting platform position creating appropriate arc and generating force on the ball in a straight line

– Three finger shooting: starting at the shooting platform and isolating the shooting hand by hovering the non-shooting hand beside the ball and taking the shooting pinky and ring finger off the ball. This helps athletes feel their index finger as the last to touch the ball at the critical instant

– ABC shooting: starting with a prepared wrist (flexed at 90 degrees showing the palm to the ball) the player catches the ball in the shooting pocket and deliberately traces a straight line ball path to their shooting platform. This helps athletes avoid any negative energy during the upward motion toward the shooting platform while also emphasizing flexing the wrist to create a stable shooting platform

We are now 9 months post rebuild. So I thought I would video his shot again to see how far we have come starting with a new shooting diagnostic:

As you can see there have been changes in the categories that we isolated. Though there is still work to be done, we are trending in the right direction. Now for some video evidence:

I maintain that the most important part to getting athletes to buy into long and arduous mechanical changes is how you prepare them for it. Then, once they experience success, you can celebrate the small victories and keep moving forward. In Deonte’s case, the last game of first semester deserves one such celebration:

Team high 18 points on 50% shooting from the field and 44% from the 3pt line. A step in the right direction.

TL;DR – Coaches shouldn’t shy away from coaching technique regardless of how engrained it is. Just make sure you prepare your athletes for the process, chunk it up, and celebrate the small victories. Throw out “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and replace it with “If it ain’t broke, make it better than it was before.” Oh, and Lonzo Ball should definitely fix his jumper, it’s busted.

JP

Hi Jackson,

Interesting post, great to see that your efforts with Deonte seem to be paying off. From what you have mentioned it also seems testament to your athlete’s character that he has the perseverance and persistence to commit to the changes over such a sustained period of time. I’m sure (and I know) plenty of USport athletes that would not have the same level of motivation to achieve this at their stage of the pathway.

Working within an invasion game also I am cognizant that executing a desired technique such as shooting in a closed setting is one thing, but being able to replicate this consistently within a high stress, opposed based environment is a formidable challenge.

In addition to breaking down Deonte’s shooting technique I would be interested to hear how you both addressed his shooting form within an opposed based environment? Were there struggles with his execution transition from training environments to games and if so how did you overcome these?

Jackson, great post and fantastic analysis. I too am interested in some of the strategies you used to change his form. This is very interesting from a motor learning standpoint. I am intrigued by the use of behaviour versus “top-down” methods. That is, behavioural training would be more about guiding the movement with lots of feedback (internal or external) or mechanical means of isolating a particular aspect of the movement. For example, one intervention I used in rugby was devising a surgical tube anchor rope with harnesses for about four players to work on defensive alignment. Essentially, the player were forced to maintain correct spacing and ability to work with players beside them as the rope would “correct” anyone who would move out of the pattern. This was provided a form of inherent feedback where players could self regulate toward the “behavioural” intervention without much feedback from the coach. The trick came when they tried the skill in the real life setting to see if there was any permanence in the change, which there was..(most of the time). Top down approaches would be much more cognitive in nature and have the athlete explore subtle changes in execution while executing a skill in different contexts (i.e. no pressure, some pressure, full pressure.. or distances, locations etc). In many ways the top down approach is a kin to deliberate practice, and likely takes longer to get a desired change, however, research suggests that the change is more permanent in the real world. I am always fascinated by how interventions could be designed to foster both behavioural and cognitive approaches. Thoughts?

Very interesting topic that has had an impact on the success of an individual and our team. There are definitely characteristics of an athlete which make each philosophy more appealing. Current basketball culture has a prevalence of not wanting to admit being wrong, or not knowing the answer. A level of security and self confidence is needed to undertake this level of change by an athlete and a coach. It is also interesting to consider the “lost time” of such a substantial change. I feel it’s difficult for coaches to have the level of investment in an athlete’s future. At the USports level you would identify the problem until the first year, fix it inthe second and have the benefits for the final 3 seasons. My final comment would be to consider the coaching time demand needed to make this change. The majority of USports programs rely on volunteer assistants and head coaches with secondary responsibilities. Time demands are far to often a significant factor in choosing the development path of an athlete.