We would like to like to dedicate our Digital Story assignment to the life and work of Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew. We hope to pay tribute to Maskegon-Iskwew by adding layers of sounds to Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s recording of a poem entitled Disintegration. This poem was composed by Greg Daniels and was featured on Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s website, Speaking the Language of Spiders. Additionally, we have selected the images that accompany Disintegration from Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders to as a way reflect further on this work. Before we begin, we would also like to acknowledge that we are white settlers living and learning on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ speaking xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) – People of the River Grass.

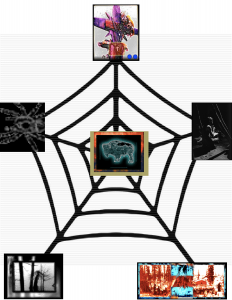

Speaking the Language of Spiders is a unique cyberspace that uses hyperlinks to showcase the poems of many Indigenous artists such as Greg Daniels, Lynn Acoose, Cheryl L’Hirondelle, etc. It uses a non-linear method of site navigation that is disorienting and challenges colonializing societal norms about how websites should be consumed. An eloquent statement made by a colleague of Maskegon-Iskwew named “S.U.” on why Speaking the Language of Spiders is formatted the way it is can be viewed here. The website is formatted as a web of knowledge, where each hyperlink of an image takes the user to a poem. The image of the buffalo looms in the corner of each page, and upon clicking it the user is returned to the centre of the web(site).

Speaking the Language of Spiders was a ground-breaking website that encouraged other Indigenous artists to use new media to showcase their artwork. A friend of Maskegon-Iskwew, Cheryl L’Hirondelle created a beautiful rendition of Speaking the Language of Spiders entitled Loving the Language of Spiders. In this tribute, Maskegon-Iskwew’s is remembered through snippets of conversations and memories and stories about his work. These are paired with artistic interpretations of each poem. We hope to honour Maskegon-Iskwew’s work by adding another layer to Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s rendition of Disintegration. We chose this poem because of the imagery it evoked for us and the sense of passing we felt after reading it.

Furthermore, we view Speaking the Language of Spiders as an example of Indigenous Futurism because it embraces technology to create an Aboriginally-determined cyberspace where Indigenous voices are at the forefront and colonial notions of rapid consumerism are restricted. We also envision Speaking the Language of Spiders as an illustration of screen sovereignty. Kirsten Dowell defines screen sovereignty as, “the articulation of Aboriginal people’s distinct cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through cinematic and aesthetic means” in Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World (Dowell, 2013, p. 2). To illustrate, Maskegon-Iskwew engages with screen sovereignty by demonstrating Indigenous artists’ collective identities through self-representation. He also uses Indigenous hypertextuality by creating an interconnected virtual mindmap and linking layers of poems to images (Haas, 2007, p. 83)

Here is our interpretation of Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s audio podcast of Disintegration. After you have listened to our recording, you can find images from Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders and a paragraph where we reflect on our positionality.

We created a spider web to represent the connections between the poem Disintegration on Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders.

As previously mentioned, we are interacting with the Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s cyberspace as white settlers. We will reflect further on our positionality and how it affects how we engage with the Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders webpages. Further, we would like to also reflect on how our tribute and Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s tribute to Maskegon-Iskwew differ based on our respective positionalities. To clarify, we are not responding directly to the content of L’Hirondelle’s tribute, but rather the ways that she is able to interact with Maskegon-Iskwew’s memory and the Speaking the Language of Spiders website.

Cheryl L’Hirondelle is a woman of Metis/Cree-non status/treaty, French, German, and Polish descent. She was part of creating the Speaking the Language of Spiders website alongside Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew. As a result, she was at the forefront of shaping Indigenous cyberspace. L’Hirondelle’s motivation may have been similar to that of Lewis & Skawennati (2005) when discussing their involvement with CyberPowWow. “As like-minded people [Aboriginal contemporary artists separated by vast distances], we saw the internet as a valuable tool for community building” (p. 109). Using the internet as a tool, L’Hirondelle, Lewis, and Skawennati, all connected this group despite the large degrees of separation between them.

In comparison, as millennial white settlers, we have become accustomed to websites that prioritize a straightforward, friendly, and linear user experience. The viewpoint that facilities this system – Western and colonial – is the perspective we have become attached to. Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders challenges our experiences because it does not adhere to colonial norms. However, Speaking the Language of Spiders was not created simply so that non-Indigenous peoples could have their assumptions challenged. Speaking the Language of Spiders is also an example of screen sovereignty. As Kirsten Dowell highlights, “… the consideration of an Aboriginal audience for Aboriginal media also expresses visual sovereignty” (Dowell, 2013 p. 3). Speaking the Language of Spiders was created by Indigenous peoples for Indigenous peoples to engage with Indigenous new media.

Speaking the Language of Spiders and Loving the Language of Spiders are Aboriginally-determined cyberspaces by Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew and Cheryl L’Hirondelle, respectively. As guests in these cyberspaces, we are honoured to be interacting with these sites.

References:

HunteR4708, creator. Knock on the Door. Freesound.org, 3 Dec. 2014, https://www.freesound.org/people/HunteR4708/sounds/256513/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

—, creator. Rain Interior Perspective. Freesound.org, 28 Oct. 2015, https://www.freesound.org/people/HunteR4708/sounds/326359/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Tomlija, creator. Kicking an Empty 20 Oz Beer Can. Freesound.org, 12 Oct. 2010, https://www.freesound.org/people/Tomlija/sounds/106611/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Daniels, Greg, author. “Disintegration.” Isi-Pikiskwewin Ayahpikesisak (Speaking the Language of Spiders), 1996, http://www.spiderlanguage.net/disintegration.html. Accessed 2 Dec. 2016.

Dowell, Kirsten. “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” in Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, pp. 1-20. University of Nebraska Press.

kangaroovindaloo, creator. Medium Wind. Freesound.org, 10 Nov. 2013, https://www.freesound.org/people/kangaroovindaloo/sounds/205966/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Haas, Angela M. “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice” in Studies in American Indian Literature, 19.4, pp. 77-100. University of Nebraska Press.

L’Hirondelle, Cheryl, performer. Disintegration. SoundCloud, 19 Apr. 2012, https://soundcloud.com/cheryllhirondelle/disintegration. Accessed 1 Dec. 2016.

—, writer. “The Spider Takes Many Forms.” Loving the Spider, 2012, http://lovingthespider.net/?page_id=177. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Lieberkind, Patrick, creator. Dark Ambience. Freesound.org, 2014, https://www.freesound.org/people/PatrickLieberkind/sounds/244961/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Maskegon-Iskwew, Ahasiw, aritist. “Buffalo.” 1996.

—, artist. CyberPowWow Cross. 2012.

—, artist. “Prairie Piece.” 1996.

—, artist. “Spider.” 1996.

—, producer. “Spider Language.” Isi-Pikiskwewin Ayahpikesisak (Speaking the Language of Spiders), 1996, http://www.spiderlanguage.net/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

—, creator. Tipicabin3. 2012.

—, artist. White Shame. 2012.

Tricia Fragnito, Skawennati, and Jason Lewis, curators. “Welcome to CyberPowWow.” CyberPowWow, 2006, http://www.cyberpowwow.net/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.