(This post is a response to the online module “Representing Reproduction: Popular and Political Narratives”.)

What struck me most about this exploration of the way in which biopolitics generally and the abortion debate specifically are represented, was that the module – particularly Heather Latimer’s writings – noted that not only is the presence of representation important, but also significant is the means of representation, namely the language and terms used.

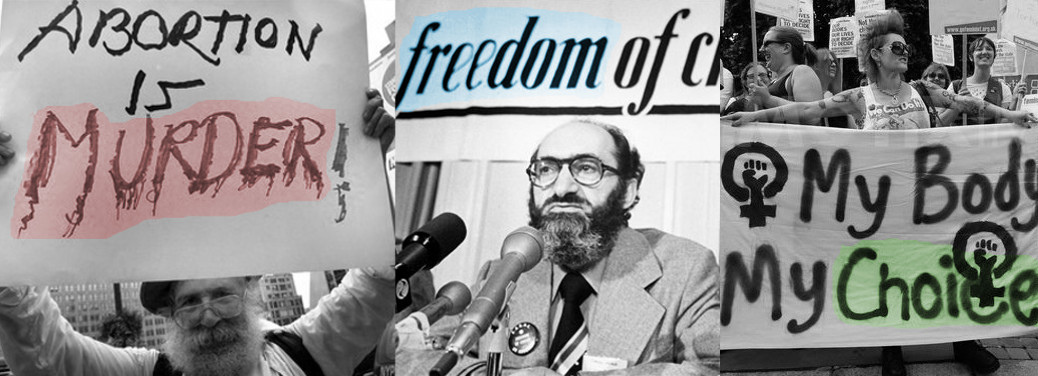

Latimer notes that the language of reproductive representation and discussion has carried over from abortion debates of the 1980s. “Freedom”, “choice”, and “privacy” have been words around which to structure pro-choice advocacy (though Latimer notes their potential to also be employed in denying women abortion rights). Even terms such as “pro-choice” and “pro-life” are similar carryovers and our continued attachment to these specific words facilitates a continued understanding of the debate as consisting of dualistic categories. Such words do not simply play a representational role, but also impact how meaning is structured in these debates.

In addition to the above examples, the instance of language that stood out to me while going through this module was when, in a 1970 radio interview with Dr. Henry Morgentaler, a woman caller speaking about abortion says, “It’s just plain murder”. The word “murder” that she chooses to use carries a complex set of implications. It links abortion to gang shootings or serial killers or other such horrible things with which the word is associated. Not that this woman articulates such connections directly, but her choice of words suggests this broader context of use. The caller’s word choice also says, without her having to verbalize it specifically, that the fetus is a person with the same rights as any other person under the law. On the other side of the debate, the phrase “to terminate a pregnancy” is deliberately implemented in order to shift the focus away from the debate about personhood and the rights of a fetus.

“Murder”, “pregnancy termination”, “the ‘A’ word” – three different references to abortion, each word or phrase carrying its own set of connotations that influence how we understand the issue. As evidenced in this module’s exploration of representation of the abortion debate, language has immense power in structuring meaning.

In terms of the teaching format of this module, I appreciated the variety of media used to communicate ideas (videos, journal articles, powerpoint slides, etc.). That said, the main thing that is lacking in this online format is the interaction with fellow students and the in-person discussion that can be generated around these topics, which, for me at least, is an important part of learning and understanding.