First Nations of the Canadian Pacific Northwest take a stand against Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans to maintain the closure of the commercial herring fishery.

I would like to recognize that this post was researched and written on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territory of the Musqueam people.

This past spring, there were a string of successful movements by Canadian First Nations to protect the herring of the Pacific North West. The Haida nation went to court to ensure the commercial herring fishery was closed in and around Haida Gwaii (McElroy, March 2015). The Heiltsuk Nation protested and successfully closed the commercial herring fishery along the central coast of British Columbia (CBC News, April 2015). And more recently, the Heiltsuk Nation has called for the continued closure of the fishery into 2016, and are collaborating with the Nuu-chah-nulth and Haida in this matter (Shore, June 2015).

Herring are both an economically and culturally important resource to many Coastal First Nations in British Columbia. They are both harvested for use, and play an integral role in the coastal ecosystems which are relied on by many (Pacific Herring, 2015). The herring fishery crashed in the 1970’s due to over-exploitation by commercial industry through the mid-1900’s. Since then, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has created an Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for the Pacific Herring, in which it establishes management objectives and outlines allocations for harvesting. However, the plan is not legally binding, and only provides a guide for the DFO and Minister to make management decisions about the stock (FAO Canada, 2015).

A major issue with the way the Department assessed the stocks and made the corresponding management decisions this past spring, was that they did not consult adequately with involved First Nations. Priority access rights to the fishery – over commercial and recreational – are assigned to First Nations groups in the managed stock areas. However when the fishery was opened this past spring for the first time since 2006, First Nations groups were not even using the licences that had been allotted to them because of their concern for the security of the herring stock (Global News, 2015). In spite of the fact that First Nations traditional knowledge is listed as one of the main sources of information used to dictate management, this level of concern for the stock in the spring was clearly not understood by the DFO through any of the consultation that did occur, giving us an indication that the consultation was minimal at best.

Huge concern for the stock is expressed by First Nations due to a combination of ecological, management and social factors. To mention just a few… the changing marine environment due to climate change means that the static models used by the DFO for herring have huge error, the fact that global populations are increasing will inevitably increase pressure on the fishery which is still in a negative growth trend, and healthy populations of forage fish – like herring – are key to the overall health and therefore ability to harvest from the entirety of ecosystems along the Pacific Northwest (Pacific Herring, 2015).

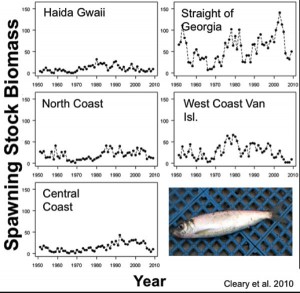

Image 1: Biomass of reproducing stocks of herring from 1950 to 2010, in various localities along the Coast of British Columbia (http://www.pacificherring.org/facts). It is clear that in some stocks there was continued decline even when the fishery was closed from 2006 on.

Although the Integrated Fisheries Management Plan is not legally binding, the right for First Nations groups to play an integral role in consultation is. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans need to heed the advice of these knowledgable, experienced communities, because it is with the insight of First Nations groups along the B.C coast that the herring stock will have it’s best chance at recovery. The DFO needs to incorporate the principles of “co-management” in their consultations with First Nations, rather than simply establishing contact to fulfill obligations.

A brief and insightful statement about the prospect of co-management in regards to marine resources in the Pacific Northwest can be found here: https://vimeo.com/93050926

References

Canadian Press, The Globe and Mail. “First Nation occupies fisheries offices in B.C. as herring fight escalates.” The Globe and Mail. March 30, 2015. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/first-nation-occupies-fisheries-office-in-bc-as-herring-fight-escalates/article23690720/

Canadian Press, Global News. “First Nation vows to interfere in B.C. herring fishery.” Global News BC. March 23, 2015. http://globalnews.ca/news/1899297/first-nation-vows-to-interfere-in-b-c-herring-fishery/

The Early Edition, CBC News. “Heiltsuk protest shuts out commercial herring fishermen.” CBC News, British Columbia. April 2, 2015. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/heiltsuk-protest-shuts-out-commercial-herring-fishermen-1.3019583

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. “Integrated Fisheries Management Plans – Pacific Region – Pacific Herring.” Pacific Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Date last modified: March 20, 2015. http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/mplans/2014/herring-hareng-2013-2014-sm-eng.html

McElroy, Justin. “Haida Nation win injunction against commercial fishery on Haida Gwaii.” Global News BC. March 6, 2015. http://globalnews.ca/news/1869522/haida-nation-win-injunction-against-commercial-fishery-on-haida-gwaii/

Pacific Herring: Past, Present and Future. 2014-2015. Accessed October 2015. http://www.pacificherring.org/home

Shore, Randy. “First Nation Heiltsuk calls for extension of herring fishery closure.” The Vancouver Sun. June 8, 2015. http://www.vancouversun.com/First+Nation+Heiltsuk+calls+extension+herring+fishery+closure/11117007/story.html?__lsa=6af5-cc30