The Vancouver Comic Arts Festival (better known as VanCAF) was launched in 2012, as a two-day celebration centered on comics and the illustrative / visual and literary arts more broadly (Demonakos, 2016). While VanCAF does not specifically focus on QTBIPOC issues and activism, the space itself has been made a

translocal and transnational space through artistic disidentifactory practices that rewrite common narratives of comic storytelling and the mainstream comic art environment. As described by Bachetta et al. (2015), placemaking is the actual reconceptualization and materialized production of space for QTBIPOC and by QTBIPOC subjects (p. 775). By highlighting the interconnections between the emergence of imagined worlds, material spaces and cyber spaces, the placemaking of QTBIPOC at VanCAF shows the importance of difference and moves us beyond Vancouver (Bachetta et al., 2015, p. 773). While the festival takes place in Vancouver, the festival ultimately brings together indigenous artists as well as settlers of colour from various diasporic communities across spaces, exceeding the limited notion of the ‘local’ as removed from globality.

One of the workshops featured at VanCAF 2017 was “Queer Witches of Colour: How Fantasy Can Empower Us All.” Panelists included Joamette Gil, Der-Shing Helmer, Judy Jong, Jayd Aid-Kaci and Jade Feng Lee—all of whom have explored the possibilities of reimagining fantasy in their work despite and as a result of the genre’s Eurocentric reputation (Young, 2015, p. 1). The event’s description states: “[f]antasy is a genre that lets us escape into worlds of magic and supernatural possibility” (Hamada, 2017). Disidentification from the norms of fantasy storytelling (e.g. centering of whiteness and cisheteronormativity) is ultimately descriptive of the survival practices that are taken up in navigating the constraints presented by dominant interrelated systems of oppression (Munoz, 1999, p. 4). As pointed out by scholar Helen Young, the racial, as well as sexual and gendered discourses that circulate in fantasy works often invisibilize whiteness as a racial position, as it is constructed as the default or norm (2015, p. 1). Through queering, the escapist tendencies of fantasy are used as a means of imagining alternate spaces, futures and ways of being in the world for QTBIPOC as a site of ‘re-humanization’ including through realms of the non-human or less-than-human.

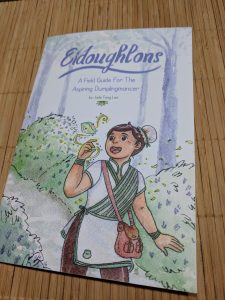

Debuting at VanCAF 2017, Feng Lee’s zine Eidoughlons: A Field Guide for the Aspiring Dumplingmancer catalogues various types of dumplings, simultaneously disidentifying with quest fantasy or heroic fantasy and ethnic storytelling (i.e. the centering of food and mythologies in storytelling) by the joining of the two into one form. Eidoughlons highlights the significance of the intergenerational transmission of knowledge in a fantastical manner, imagining other ways of being in the world and presenting alternate spaces for processes of identity recovery for QTBIPOC that do not necessitate rejecting our families and cultural backgrounds.

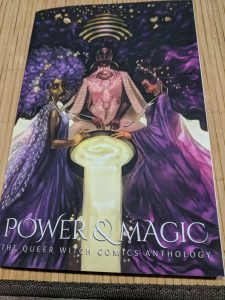

The creation of cyberspaces by and for artists of colour—particularly QTBIPOC—have created spaces for collaboration and community-building. In an interview, editor, artist, owner of Power & Magic Press—a QPOC-operated publishing house—Joamette Gill (one of the panelists) points to the formation of online groups for women and non-binary people of colour to collaborate that led to the production of Power and Magic (Moondaughter, 2016). The formation of cyber spaces invokes the queering of space by and for QTBIPOC, particularly through the navigation between queer and trans of colour imaginaries, cyberspaces and lived reality. The retooling of space across different mediums—cyber, fantastical and material spaces—as the non-human and more-than-human (both tending to be racialized sites) are invoked as routes of rehumanization.

The presence, projects and work of QTBIPOC that has emphasized placemaking that moves beyond hegemonically defined notions of space, as the place of QTBIPOC at VanCAF 2017 is entangled in a broader web of diasporic and colonial formations that operate across a multitude of spaces.

References:

Demonakos, A. (2016, November 1). VanCAF returns with a new festival director and advisory board. Vancouver Comic Arts Festival. Retrieved from http://www.vancaf.com/2016/11/01/vancaf-returns-with-a-new-festival-director-and-advisory-board/

Hamada, J. (2017, May 11). Vancouver comic arts festival 2017. BOOOOOOOM. Retrieved from https://www.booooooom.com/2017/05/11/vancouver-comic-arts-festival-2017/

Bacchetta, P., El-Tayeb, F., & Haritaworn, J. (2015). Queer of colour formations and translocal spaces in Europe. Environment and Planning D, 33(5), 769-778.

Munoz, J. E. (1999). Performing disidentifications. In Disidentifications, 1-34.

Moondaughter, W. (2016, February 1). Creating queer and POC-centric comics: Joamette Gil. Sequential Tart. Retrieved from http://www.sequentialtart.com/article.php?id=2877

Young, H. (2016). Race and popular fantasy literature: Habits of whiteness. New York: Routledge.