Following the Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation of the 1860’s, opportunity began arriving to newly-freed African Americans. However, the Reconstruction Era demonstrated an unwillingness from Southern States in providing racial equality. As seen through Jim Crow Laws, African Americans continued to face prejudice, both on a legal and civil level. In an attempt to escape the Jim Crow South, millions of blacks left for Northern Cities, seeking social justice and labor opportunities. New York City became one of many destinations for the Great Migration, and beginning in the 1920’s, saw African Americans concentrate into Harlem. This New York City ghetto began producing a boom of distinct African American Culture. The Harlem Renaissance, caused by the Great Migration, redefined culture to an unprecedented level for African Americans.

Jim Crow South

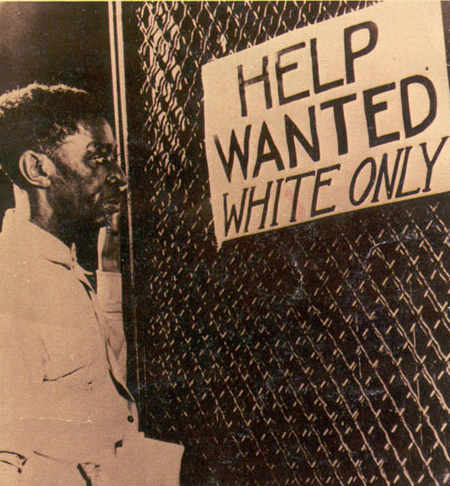

The Jim Crow South demonstrated a seeming impermeability towards black equality, regardless of their emancipated status. The federal government’s attempt to provide civil rights to blacks was largely curtailed by the passing of segregation laws in southern states. These laws mandated a separation of blacks from whites in public schools, restrooms, public transportation, drinking fountains, and many other public goods and facilities. Described as “separate but equal,” Jim Crow Laws left African Americans to an objectively inferior living condition compared to whites, in which jobs, education, and housing quality were systematically limited (Franklin).

The South was also home to the Ku Klux Klan, a white-supremacist organization responsible for many of the systematic lynchings of blacks. Formed in 1865 by veterans of the Confederate Army, the KKK was responsible for the murder of thousands of African Americans, in attempt to suppress black voting. Racist sentiments were present beyond the hatred of the Klan, demonstrated by the legal distinction made through Jim Crow laws, and mass public opinion within the South (NAACP).

Push factors for Southern Blacks continued to surmount at the turn of the century, in which the Southern economy crashed. Jim Crow laws showed little sign of repeal, continuing the systematic hardships facing African Americans. Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers continued to work in fields, regardless of their emancipated status. Furthermore, beginning in 1913, many Southern states were facing economic depression, caused by a drop in cotton price. A year later, an insect known as the boll weevil arrived from Eastern Texas, decimating cotton crops. Additionally, Mississippi experienced severe flooding in 1915, destroying farmland, as well as many African American homes. Share croppers and tenant farmers faced significant economic repercussions from these calamities (The Economist).

Opportunity in the North

While many African Americans were experiencing the greatest despair of the Jim Crow South era, Northern cities such as New York offered fresh job opportunity. World War One led to European powers looking to the United States in satisfying their industrial needs. Simultaneously, the war cut off cheap labor arriving from Europe. Production reached higher quotas when the United States formally entered the conflict in 1917. Northern industrialists looked to Southerners, mostly African American, to provide cheap labor in factories. Additional incentive was offered in the form of free train tickets to the North, as well as higher wages. A southern sharecropper could expect to receive fifty cents to two dollars a day, whereas industrial wages could reach five dollars a day (Foner).

The North provided more than job opportunities for African Americans. Jim Crow laws were exclusive to Southern states, demonstrating a dichotomy in racial distinction. The North was a safe haven from much of the racial violence, such as lynching. Furthermore, it enabled African American youth to attend unsegregated public schools. Naturally, the single public school system, shared by white and black students, enabled a much higher quality education than segregated alternatives. An unsegregated school system provided a two-fold benefit to black migrants, both in quality of the subject matter being taught, and the dissolution of racial boundaries amongst students.

The First Great Migration dramatically altered Northern cities, such as Chicago, Detroit, and New York. 1910 through 1930 marked this “Great Migration” of 1.6 million Africa Americans to urban hubs in the West, Midwest, and Northeast. The journey, coined as an exodus, reflected a religious sentiment held by many Christians heading North. It was described as the “promise land,” alluding to the biblical tale of the Israelite slaves’ emancipation and departure from Egypt. This religious significance can be traced back to biblically-coded songs performed by slaves. The slave song, “Steal Away to Jesus” shows a lingering desire from blacks to “Steal away to Jesus, Steal away home,” which could be traced back to the peculiar institution (NAACP).

Northern Attitude

Despite the numerous advantages offered to African Americans, racism did not end upon arrival into Northern cities. Northerners had defended emancipation, however many did not expect a migration of millions of blacks into their cities. The Great Migration led to race riots in over three dozen cities in 1919, commonly referred to as Red Summer. This was caused by anti-Bolshevik sentiment in the United States, where some believed African Americans would work alongside Bolsheviks to take over the entire nation, ‘converting’ it to socialism. Other’s feared blacks would effectively take over the labor opportunities in cities. With the riots responsible for the deaths of over sixty blacks who had been either lynched or shot, the NAACP sent a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson, reading “The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?” The final riot took place on October 1st, in Elaine, Arkansas (Erickson).

Destination: Harlem

New York City, at the time nearing the first great migration, showed volatility in the city district of Harlem. Designed in the early 19th century as an upper middle-class suburb for whites, Harlem had become a destination for a large number of European immigrants being employed in factories. European migration into a relatively high-class district was possible due to a drop in real estate prices, caused by construction delays of a subway. By 1900, Harlem’s population consisted of 150,000 Italians. Additionally, the Jewish population had bolstered from 12 in 1869 to 200,000 by 1915. The once exclusive district was abandoned by the white middle class, who relocated further North (Gill).

It was not until the end of the 19th century that Harlem became the focus of black migrants arriving in New York. Despite the freedoms offered by the North, racial tensions were still existent in these heavily-populated cities. Ethnic groups naturally gravitated together to form communities within the city. This was due in part to ethnic similarity, as well as protection from racially-driven riots. During the late 19th century, African Americans began moving into “negro tenements” near West 130th Street and 125th Street. By the turn of the century, ten’s of thousands of African Americans presided in Harlem. However it wasn’t until another, more severe housing market crash in 1903, that Harlem opened up and became the capital of African American culture (Gill).

Black entrepreneurship helped to provide black housing within the Harlem district. The housing market crash of 1903 left landlords unable to find white renters for their properties. In response, Philip A. Payton, Jr, an African American real estate entrepreneur, formed the Afro-American Realty Company. His company was responsible for acquiring devalued housing structures from white landlords, and renting them to newly-arriving black families. Payton marketed his business to black investors as a means of economic and social benefit, stating, “Today is the time to buy, if you want to be numbered among those of the race who are doing something toward trying to solve the so-called ‘Race Problem.’” The Afro-American Company fought competing white real estate companies (who rented exclusively to white tenants), providing housing only to African Americans. In December of 1905, the New York Herald predicted, “ real estate brokers predict that it is only a matter of time when the entire block, to Eighth Avenue, will be a stronghold of the Negro population,” (Gill).

The New Negro Movement

A bolstering culture in 1920’s Harlem, called the “New Negro Movement” marked an era of cultural significance for African Americans in New York. In 1917, Three Plays for a Negro Theatre premiered at the Harlem Opera House. Written by Ridgely Torrence, these plays rejected the “blackface” and minstrel show tradition of black dehumanization in theatre. African Americans were, for the first time in theatre, portrayed as wielding sincere human emotion, as opposed to the racial stereotypes of “blackface” in traditional minstrel shows. James Weldon Johnson, the first black executive secretary to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, called the premiere, “the most important single event in the entire history of the Negro in the American Theater,” (Foner).

The New Negro Movement marked the beginnings of a rippling and dynamic culture for African Americans living in New York City. Harlem continued to increase its African population. Blacks went from constituting 30% of the district’s population in 1919 to over 70% by 1930. Within the New Negro Movement, which would later be famously renamed the “Harlem Renaissance,” 118,792 whites left the district while 87,417 blacks arrived. More importantly, the renaissance demonstrated a changing ideology held by, and towards African Americans. No longer was the African American categorized as a rural field worker, but rather, as a distinguished member of an urban population. The Harlem Renaissance was responsible for a flourishing of visual art, literature, intellectualism, and religious inspiration. The day’s of enslavement had past, succeeded by racial pride, and white’s interest, whether cynical or not, in the cultural lives of African Americans (Gill).

No longer was the African American categorized as a rural field worker, but rather, as a distinguished member of an urban population. The Harlem Renaissance was responsible for a flourishing of visual art, literature, intellectualism, and religious inspiration. The day’s of enslavement had past, succeeded by racial pride, and white’s interest, whether cynical or not, in the cultural lives of African Americans (Gill).

Musical novelties were also produced in Harlem, blurring the lines of class distinction. Southern blacks had brought a jazz influence to Harlem. Traditionally, jazz bands consisted of only brass instruments. Upon its arrival into a culturally volatile Harlem, jazz took on a new meaning with the advent of the piano. While jazz was generally considered a musical genre of the rural African American, the piano was distinguished as an instrument of the wealthy. This fusion of instruments formed a new musical genre known as the Harlem Stride Style. Along with this musical advent, came white New Yorkers seeking a new sort of excitement through Harlem’s emerging artistic scene. The Harlem Stride Style was responsible for a diffusion of more than just classes by allowing whites to enjoy, as well as work in composition alongside African Americans (Foner).

Bibliography

Erickson, Alana “Red Summer” in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, NY: Macmillan, 1960.

Franklin, John Hope and Alfred A. Moss, Jr. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African-Americans, 8th Ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Foner, Eric. Give me liberty!: an American history. Seagull third ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

“NAACP: A Century in the Fight for FreedomThe New Negro Movement.” The New Negro Movement. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/naacp/the-new-negro-movement.html (accessed March 16, 2014).

Gill, Jonathan. Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America. Grove/Atlantic, 2011.

Jes’ a-lookin’ for a home: boll-weevil trouble. 1998. The Economist, June 27, 1998 v347 n8074 p29

Kaplan. Help Wanted Whites Only. N.d. America’s Black Holocaust Museum, Georgia. http://www.abhmuseum.org/. Web. 20 Mar. 2014.

Reuben. Harlem Renaissance Clothing. N.d. SHS AP Literature & Composition Wiki, Harlem. http://shsaplit.wikispaces.com/. Web. 23 Mar. 2014.

“Riots Sweep Chicago.” Chicago Defender 2 Aug. 1919: 1. http://cameronmcwhirter.com/. Web. 18 Mar. 2014.

Smallwood, Arwin D., and Jeffrey M. Elliot. The atlas of African-American history and politics: from the slave trade to modern times. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Print.