I’m a world expert as, in my first BA (I did two and worked in between; with grants for both, and working part-time in the second) I was a terrible student. I didn’t go to lots of classes, I did as little work as possible, I just about got through 1st year exams then flunked 2nd year (and was OK after). I still learned a lot, partly as I was going to other classes (this was in a place where you could go to any lectures, in any subject, even if you weren’t registered in that course) and read things.

I’ve also been a student in more than one country and continent, including a PhD that was, to put it diplomatically, “intense.”

Tips:

1. come to class: even if you’ve not prepared or done the reading, even if you think that you’ll fall asleep. I manage not to because I teach standing up. If I’m sitting down before 10 a.m., I will fall asleep. I know this from conferences.

2. make sure that you’re comfortable in class but not too comfortable (see 1 above), bring plenty of water, and in my classes you can always bring coffee, tea, food, whatever you need.

3. this is all very “humans are animals” advice so far, which fits our course! Remember that you are an animal with animal needs. Stay hydrated, eat regularly and healthily: higher-fibre carbs, fats, leafy greens, things with B vitamins and iron: I’m mostly vegetarian-to-vegan so I need to watch that, and I’ve been ill in the past from low iron. (Don’t do that. Like a lot of advice here, it’s “do what I didn’t do or what I know that I ought to do and don’t always do because, well, I’m human and to err is human.”)

A good UBC campus tip: Seedlings, cheap student co-op daily soup/lentil stew type things with bread, in Koerner grad studies building. And The Soup Market in the Nest, lower floor. Some more UBC food tips are here. I also love Uncle Fatih’s Pizza because it’s one of the few places on campus that are open late. The University Village might seem like a long walk, but given the line-ups in the Nest, the 10-minute walk is worth it. Pizza Garden gets my seal of approval for good pizza and is open late (yes, I love pizza) and the underground food court is a good thing and open at the weekend.

I’m also an advocate for chocolate. Life should be happy too, not just functional.

4. Get as much sleep as you can. Sleep is very important and often underrated. One of the bravest toughest things that you can do as a student is to defy peer pressure, not to stay out super late, not to try to keep up with people being competitive about how little they’re sleeping (and how much or how little they’re studying / working, depending on the local culture; I’ve lived through both extremes). Sleep does awesome things to your brain and your learning.

5. Human and other animal company. People to talk to, or not. My spouse and I spend a lot of our time reading quietly together. I’ve seen this called “sociable solitude,” in relation to medieval monastic communities, and later ones: silent monks are far from solitary and isolated. Our course will, I hope, create study groups and community.

(Here’s a squirrel-moment from a previous class.)

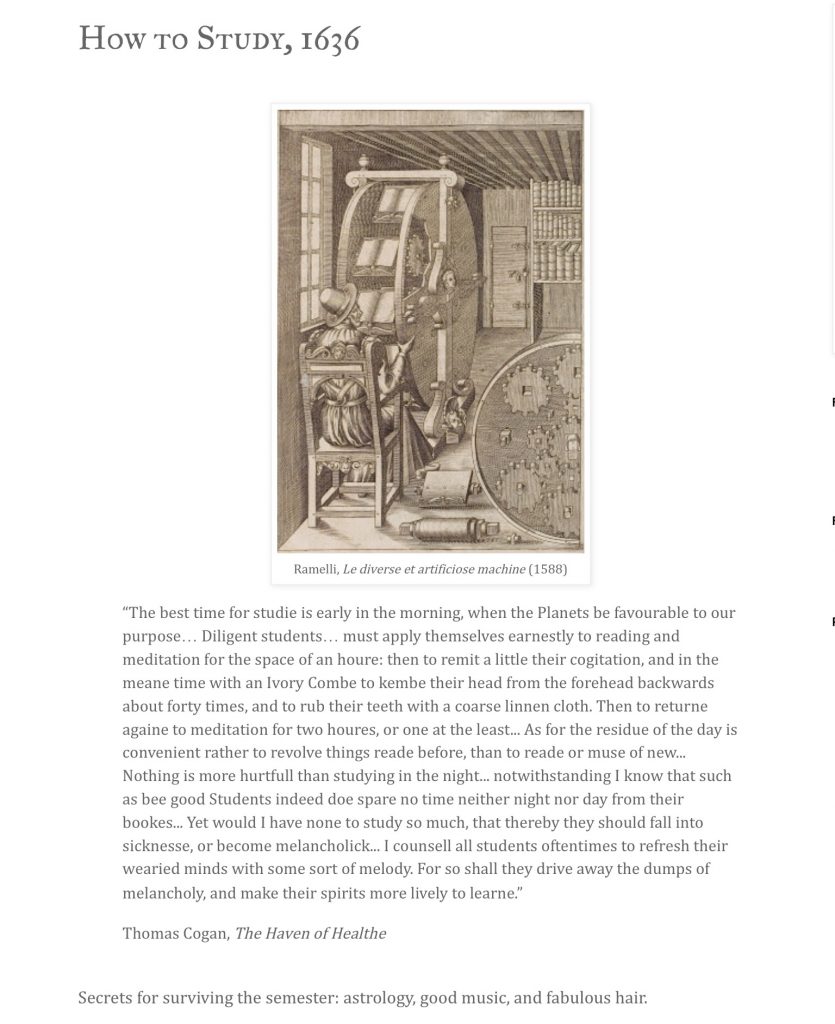

6. Music last thing at night before sleep. Music also does good things to the brain, so if it helps you can tell yourself that this is for the good of your studies, as well as for yourself and your wellbeing.

7. I’m prejudiced here, but: reading, movies, TV series. In Arts / Humanities courses, the more you read—anything—the better you write, and the better and more and faster you read. I’d also advocate something that I started doing as a grad student: make sure that you are always reading (or watching) at least one thing for pleasure, and try to have at least half a day per week that is for that and for *you.*

8. Spend at least some time outside every day with green things. UBC campus is good for this. And in quiet with beautiful things: the Museum of Anthropology is wonderful for that, and as it’s free, you can just pop in for 10 minutes and spend that time with a single object (I have beginners’ French students do this, as part of their assessed coursework, so it’s both academic work and individual wellbeing). Some people meditate and do yoga for this too. I’m not a good person to talk to about that, as I find it very difficult to turn my brain off completely and get grumpy about people telling me too. Looking at something beautiful or listening to music is the closest that I can manage.

9. Try to have at least one course per term that you chose, didn’t have to do, and enjoy.

10. Try—and this is really, really difficult—not to think about grades, and rankings and classes, but instead about learning. If despondent, at the end of the week look at your notes and ask yourself: did I learn at least one thing this week that I didn’t know before, and that was curious and makes me think?

I’m hoping that RMST 221B will help with all this. You don’t need to worry about grades, as part of it is grading yourself (have a look at “assignments”) and you can be generous with yourself and with others. My default in this course is that all of you are capable of getting an A.

Some of you are first-year students, and some of you are the first people in your families to be university students. This can be a lot of pressure. You’re not alone, and there are lots of people here to help; first and foremost, other students.

Here are some more tips that I prepared for FREN 101 students, as many of them are first-years or first-time students. You’ll see some overlap with the points above.

NAVIGATION

EXAM PREPARATION AND REVISION GUIDANCE

The good news about our anti-exam is that you should not have any revision to do; and none of the sorts of “studying”—as contrasted with learning—that are needed in some other kinds of course and academic field. We are working with literature, culture, and ideas; and this is more like music or sport than, say, biology or economics. Our kind of learning is cumulative—with new knowledge building on previous acquisitions—and happens and is reinforced through regular practice. If you have been to class, worked in class, and read and thought outside class—ideally, doing a little every day—then you will have been learning all term and should be well prepared for our exam-which-isn’t-really-a-proper-exam-anyway. [I adapted this paragraph for our course.]

DORMIR est le verbe le plus important en français (nos 2-10 = RÊVER, RÊVASSER, SONGER, IMAGINER, FLÂNER, FAINÉANTER, SE PROMENER, VAGUER, VAGABONDER…)

DORMIR est le verbe le plus important en français (nos 2-10 = RÊVER, RÊVASSER, SONGER, IMAGINER, FLÂNER, FAINÉANTER, SE PROMENER, VAGUER, VAGABONDER…)

Here are some useful practical general tips and advice from Timothy Gowers (Mathematics, University of Cambridge) > scroll down to “General study advice.” What more can you do?

1. Sleep. At least 8 hours/night, every night. Sleep plays an essential role in deep learning and the consolidation of memory.

2. Electronic visual blackout before sleep. At least an hour with no electronic light-sources (i.e. screens). This can also help you to sleep. Listening to music, however, is actively encouraged: especially if it’s in French! Music can also be calming and comforting.

3. Eat well and regularly.

4. Exercise. Including during the day, outside, in the fresh air and light. While working, make sure you’ve at least stretched for 5 minutes every hour. This keeps your core muscles limber and your airways open; especially around your upper torso and shoulders. During an exam too: we will remind students of the passing of time during the exam, and one reason for that is to give us a reason to remind students to stretch out a bit. [Remind me, in our anti-exam, to remind you to have stretching-pauses.]

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=p60rN9JEapg

5. Prepare, intelligently. (See video above, which reformulates much of the information below.) Work in shorter intensive stretches (maximum 20 to 30 minutes), with regular breaks. Set an alarm or a timer, to ensure that you have a break for at least 5-10 minutes every hour. Read, watch, and listen to something relevant to the subject that you’re working on every day: even something tangential, 5 minutes of skim-reading newspaper headlines online. Anything, from anywhere, any time; it can be fun (depending on one’s definition of fun) to read, watch, or listen to something apparently random and then challenge yourself to find a connection to your subject-matter at hand (ex. Montaigne).

[This next part doesn’t really apply to our couse, but it might be useful to you for others, and especially language courses.] Doing a mini-immersion is the single best thing that you can do immediately before an exam: listen to and/or watch something the evening before your exam, read something in the morning, and then give your beautiful mind a rest to help it to be ready for the exam.

[This is universal advice for all subjects.] Cramming at the last minute is not advised, for three reasons:

(a) Most of your work is done during term, in the virtuous cycle of teaching-and-learning. There is little material that you can cram at the last minute, without taking drugs of a sort that also risk messing up memory. Literature, ideas, and the literary / literate humanities are unlike academic areas that depend on learning facts by heart, by rote, in a mechanical robotic way.

(b) Our course is like most other academic subjects in that, at a university level, in order to do well you will/should also need to show evidence of reflexion, of independent thought; of applied knowledge. This entails active new thinking during the (anti-)exam.

(c) Any field requires regular continuous work and practice. The way it is learned is more like music. An analogy: if you had a piano recital, you wouldn’t do nothing at all and then cram 18 hours’ practice the day before.

6. Some of the best revision you can do before assessed work like an exam (even our open book anti-exam, given its time limit) is testing yourself. One of the best tests of your knowledge is your capability to explain something to another person. Work in study-pairs or groups (but keep them small: 2-4 people). Meet regularly over coffee/tea (and maybe cake, du gâteau). Quiz each other. This can be done at any time, and continues to be beneficial in the week before a final assignment

7. Make sure you know where your exam is taking place, how to get to it, and how long that will take.

8. Make sure you know where the nearest bathroom is. Pay a visit before the exam.

9. Arrive at your exam early (at least 20 minutes before the start), preferably including at least 10 minutes’ walking in your itinerary to get some oxygen into your brain (but not running).

10. Don’t bring anything with you that you don’t need for the exam itself. Especially no notes, revision guides, etc. They rarely-to-never help. They often hinder. In our case for RMST 221B, you can bring and refer to books and notes during the exam. You’re better off spending those last few minutes before the exam doing deep breathing. Some people meditate. Do whatever works for you, something calm that involves breathing slowly and deeply, good for your heart-rate as well as your blood (and brain) oxygen levels.

EXAM SEASON GUIDANCE

UBC resources for stress-relief for students:

- Stress: http://students.ubc.ca/livewell/topics/stress

- Anxiety: http://students.ubc.ca/livewell/topics/anxiety

- Sleep: http://students.ubc.ca/livewell/topics/sleep (I cannot over-emphasise the importance of sleep, for general health as well as for brains & exams; UBC and research colleagues in psychology and neuroscience do too. It’s not just me.)

- Nutrition: http://students.ubc.ca/livewell/topics/nutrition-and-food

- Physical activity and recreation: http://students.ubc.ca/livewell/topics/physical-activity-and-recreation

- Events on campus: http://students.ubc.ca/success/stress-less-exam-success

- “(tutoring and) studying”

- > learning & memory

- “student toolkits”

- > “preparing for exams”

Arts Peer Academic Coaching: APAC’s coaching hours are hosted in the Meekison Arts Student Space in Buchanan D140 (down the hall from Arts Academic Advising). There are two ways to meet with a coach:

- Drop-in hours: Come by between 12pm-4pm Mondays & Wednesdays, 12pm-5pm Tuesdays & Thursdays throughout the term.

- Book an appointment in advance.

Great news – peer coaching is free! Come on your own, or bring a friend. Come by once, or several times to meet some of the different coaches on the team. O’Brien personal recommendations on and near campus (all are free to access):

- Beaches, especially in winter: Acadia, Jericho, Spanish Banks, etc.

- H.R. MacMillan Space Centre (1100 Chestnut Street, by Vanier Park): http://www.spacecentre.ca

- Pacific Spirit Park

- UBC Beaty Biodiversity Museum, inc. blue whale skeleton (free for UBC students): https://beatymuseum.ubc.ca

- UBC Belkin Art Gallery (free for UBC students): http://www.belkin.ubc.ca

- UBC Botanical Garden and Nitobe Memorial Garden (free for UBC students): http://botanicalgarden.ubc.ca

- UBC Koerner (Arts & Humanities) Library: https://koerner.library.ubc.ca

- UBC Museum of Anthropology / world arts and cultures (free for UBC students): https://moa.ubc.ca

- UBC Rare Books and Special Collections: https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca

- UBC School of Music concerts; many are free or cheap, often in the daytime, and include student recitals: https://music.ubc.ca/calendar/

- Vancouver Public Library, especially the Central Library (350 West Georgia Street): https://www.vpl.ca

- Volunteer (and learn) at UBC Farm: http://ubcfarm.ubc.ca/get-involved/volunteer-program/

Image source: Facebook > UBC Coyote

Image source: Facebook > UBC Coyote

EXAM PRACTICALITIES

WHEN & WHERE?

- See UBC exam schedule

WHAT YOU SHOULD BRING WITH YOU

- your UBC student ID

- a pen and/or pencil (I would recommend bringing three new ones that you’ve already tested out)

- water, if you wish

- a spare layer of clothing in case you get cold during the exam (cardigan, hat, etc.)

- basics such as keys, outerwear, umbrella, …

- for our exam: any books, notes, etc. from the course plus your poster (or equivalent) for your poster presentation

WHAT YOU COULD BRING WITH YOU

[I give this advice for closed-book exams where you can’t use these during the exam, but they’re reassuring so that you have something with you.]

- one index card of notes

NB: This is an exam preparation suggestion only for those students who find it worrying to have nothing with them and feel reassured to have something to look at as last-minute revision. Doing that using one pre-prepared index card is better (and writing that index card is very good preparation in its own right) than bringing backloads of papers with you.

WHAT YOU DO NOT NEED TO BRING WITH YOU

- cellphones, smartphones, tablets, laptops, headphones, and other electronic devices

- I usually recommend not bringing or using tippex / wite-out / liquid paper or erasers: in exams like ours, where you are actually writing rather than filling out scannable forms, it is better to strike through an answer that you think is wrong and then return to it when you are proofreading and editing, so that you can see your own thinking and working in such areas of uncertainty and pick up your thought where you left off before moving on to the next question. It’s possible that an earlier answer was right, and if you’ve erased it, you’ll have lost it. Also, when I am marking, I can give you at least partial marks if I can see your working, including a previous correct answer.

UBC RULES ABOUT EXAMINATIONS

You are expected to know these: it is one of your contractual responsibilities and obligations when you registered as a UBC student.

- student declaration and responsibilities

- academic honesty and standards

- student conduct and discipline

- academic misconduct: cheating, plagiarism, etc.

- student conduct during examinations

- exam policies and accommodations

- UBC grading practices

- UBC Policies and Regulations: Academic Concession

SEE ALSO

- Syllabus (2): THE RULES > Missing or rescheduling tests and examinations

- Syllabus (3): HELP