Nadja – A State of Delusion or of Reflection?

“I am the soul in Limbo” (71)

Considered one of the earliest surrealist romance books, Nadja is chock-full of wonder. Flipping through this short recollection of a haunting memory, every page tells a fragment of this mystery. Who was Nadja? And, was she truly real?

Some quick research and Nadja is actually Léona Camille Ghislaine Delcourt. However, I will focus on Nadja within these pages. Nadja isn’t introduced until page 60, yet Breton finds himself entranced with her. Her surrealist way of living, as if she were living above us all. It reflects the quote at the top–Nadja is a mystery who believes herself to be living in a forgotten world (limbo). But this forgotten world is the normal one that does not exist in her daydreams. One may call her delusional, but in reality, she seems to be the most interesting woman Breton has ever seen.

With the various pictures attached to these memories, it is almost as if Breton is trying to prove to himself that Nadja was real or show proof that she is haunting his mind. Nadja can be considered a state of mind, a cautionary tale of overindulgence. She feeds into Breton’s ego, existing as a complementary figure in his imagination.

Does it truly matter if Nadja was real? She exists in many causes to reaffirm Breton. He is fading away, whether this be in his work or life. It exists in the tortured soul of many artists that many do not understand you. What if Nadja was a remedy for self-reflection? It’s tricky to determine the exact truth of this novel, but for me, it felt that Nadja existed to examine Breton’s disconnect from the world.

Nadja’s fate is to be confined to a psychiatric institution, and Breton seems dull about this. Her carefree worldview could have been that of a delusion, one that Breton finds unnecessary to put her away. But her disappearance is what creates the longing to remember her. Whether or not she existed, Breton felt a deep connection that will forever be lost. The limits of surrealism in the real world are what Breton must come to imagine. Nadja’s once visionary surrealist mindset slowly descends into madness. When noticing the man on top of the train, Breton can begin to feed into her disillusions (or perhaps his own). However, he does not stay like this forever. Nadja must be taken away, and Breton will be alone (despite having a wife, but cast that aside for a moment). It is a devastating tale that many find themselves plagued in: a regular tale of star–crossed lovers.

“Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all.” (160)

Discussion Question:

Nadja is a book that borders on fiction and non-fiction, its photographs reaffirm Breton’s memories but Nadja herself remains an enigma. However, she exists to teach Breton valuable lessons–acting as a sort of fable. Narratively, what do you think Nadja’s role in this book is? Was she simply a woman who he could connect with who wasn’t his wife? Or perhaps did she serve a purpose in the fundamental character of Breton?

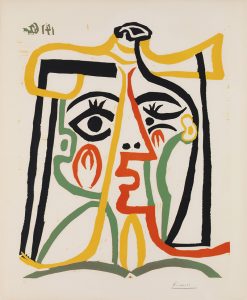

One of my favourite surrealist paintings would be “Tête de Femme” (Head of Woman) by Pablo Picasso. Despite him being a prominent cubism painter, he did dabble in surrealism