Conclusion – Money to Burn was iconic and y’all are just scared to admit it

In honour of my last blog post, I want to reflect on the many texts I have read.

In this unique sort of course, I was entirely in my element. Reading books and subsequently crying over my laptop while making memes has become my life.

I have used a variety of mediums throughout the past few weeks–ranging from works of art to my stupid memes. It really goes to show how fluid storytelling can be. The one medium I wish I had considered was doing a podcast, but I guarantee I would put too much work into dumb editing choices.

Novels

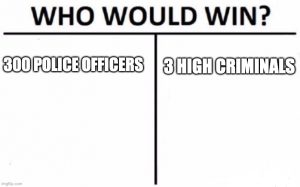

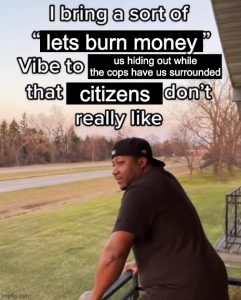

First and foremost, I am a Money to Burn defender. I will let the gay people do the crime. Even though it was not historically accurate, it was iconic. I love that this is an unpopular opinion. I personally enjoyed the stupidity of the three high criminals saying fuck you to the police holed out in that apartment. Additionally, the relationship between Dorda and Brignone was heartbreaking.

I want to bring us back to the early weeks so that I may again hate Breton in his novel Nadja. My man said, “Let me create a girl that’s so crazy that my wife would think it is okay for me to cheat on her, and then let me have Nadja worship my work.” We get it, Breton. You have no friends and no life, and you hate your wife. Yes, it was giving Manic Pixie Dream Girl, but it was also giving “Breton, you are psychotic. I hope your wife divorces you because she deserves better than your lame ass”.

I want to bring us back to the early weeks so that I may again hate Breton in his novel Nadja. My man said, “Let me create a girl that’s so crazy that my wife would think it is okay for me to cheat on her, and then let me have Nadja worship my work.” We get it, Breton. You have no friends and no life, and you hate your wife. Yes, it was giving Manic Pixie Dream Girl, but it was also giving “Breton, you are psychotic. I hope your wife divorces you because she deserves better than your lame ass”.

My most contested opinion is about Agostino. I swear on all things holy, this book is not about the Oedipal complex. I recently reread the myth of Oedipus, and my man Freud did not describe it very well. The myth was that the prophecy was for Oedipus to kill his father and marry his mother, yet he was adopted and did not want to fulfill the myth. Unfortunately, he ends up killing his birth father (whom he does not recognize) and marries his birth mother (which, again, he does not recognize). When he discovers the truth about his relationship, he blinds and kills himself. Does this really seem like someone in love with his mother? No, Freud is a loser. I enjoyed Agostino, and in my blog post, I explicitly explain the tricky line it treads on adolescence and being attached to his mother (but not in a sexual way).

The most profound novel had to be The Shrouded Woman. While I initially debated between The Shrouded Woman and The Time of the Doves, Bombal comes out on top. A unique narrative, a woman on her deathbed and dying a second death, the flipping timelines of past to present, it all perfectly encapsulates Ana Maria’s slow decline into death. I also enjoyed the language throughout the novel, especially the sentences about Ana Maria dying. Moment of silence for Ana Maria. The last few paragraphs about her succumbing to death and being swallowed up by the Earth are so profound and beautiful. This book had me questioning my own identity for a while.

The books I did not choose but are now officially added to my list are Mad Toy, The Trenchcoat, and The Book of Chameleons.

My all-time favourite quotes:

“And it was also like one of those miserable creatures whose singular torment, repeated indefinitely throughout eternity, aroused the curiosity of Dante, who would have asked the tormented creature himself to recount its cause and its particularities at greater length had Virgil, striding on ahead, not forced him to hurry after immediately, as my parents did me” (Proust p. 173)

“Hatred, yes hatred, and beneath its somber wings she breathed, she slept, she laughed; hated her now main purpose, her primary concern. A hatred that victories did not lessen but made fiercer, as if the fact of meeting so little resistance could only increase its fury” (Bombal p. 229)

“But, born of her body, she was feeling an infinity of roots sink and spread into the Earth like an expanding cobweb through which was rising, trembling up to her, the constant throbbing of the universe.And now she desires nothing more than to remain there crucified to the earth, suffering and enjoying in her flesh the ebb and flow of distant, far distant tides; feeling the grass grow, new islands emerge, and on some other continent, the unknown flower bursting open that blooms only on a day of eclipse. And she even feels huge suns boiling and exploding and gigantic mountains of sand tumbling down, no one knows where” (Bombal p. 259)

“I’m a typist and a virgin, and I like coca-cola” (Lispector p. 27)

“Returning to the grass. For that puny creature named Macabéa great nature showed itself only in the form of grass in

the sewer—were she given the thick sea or the high peaks of mountains, her soul, even more virgin than her body, would

go mad and her organism would explode, arms here, intestines there, her head rolling round and hollow at her feet—as you

dismantle a wax dummy” (Lispector p. 71)

“No woman, no girl wore a man’s fedora…” (Duras p. 12) – Tell that to 10-year-old me, you coward.

“for the first time in her life, death knew what it felt to have a dog on her lap” (Saramago p. 172) – cut to me crying.

“There was something unbearable in the things, in the people, in the buildings, in the streets that, only if you reinvented it all, as in a game, became acceptable. The essential, however, was to know how to play, and she and I, only she and I, knew how to do it” (Ferrante p. 106-107)

Money to Burn section…hehe

“The Gaucho acts as the body, solely responsible for executing the action, a psychotic killer; the kid is the brains and does the thinking for him” (Piglia p. 52)

“Life is like a freight train, haven’t you watched one of them go by at night? It goes so slowly, you can’t see the end, it seems it’ll never finish going by, but finally you’re left behind, watching the tiny redlight at the back of the last carriage as it disappears into the distance” (Piglia p. 92)

“Life is like a freight train, haven’t you watched one of them go by at night? It goes so slowly, you can’t see the end, it seems it’ll never finish going by, but finally you’re left behind, watching the tiny redlight at the back of the last carriage as it disappears into the distance” (Piglia p. 92)

“If the money were the sole justification for the murders they committed, and if what they did, they did for the money they were now burning, that had to mean they had no morals nor motives, that they acted and killed gratuitously, out of a taste for evil, out of pure evil, that they were born assassins, insensate criminals, degenerates. Filled with indignation, the citizens gathered to observe the scene, offering shouts of horror and loathing, looking like something from a witches’ sabbath straight out of the Middle Ages (according to the papers), they couldn’t bear the prospect of 500,000 dollars being burned before their very eyes, in a move that left the city and the country horror-struck, and which lasted precisely fifteen interminable minutes, which is exactly how long it takes to burn such an astronomical quantity of money” (Piglia p. 157)

“They’re made of ice, they have no pity, they’re dead. They’re like living cadavers hellbent on just one thing, discovering quite how many of us they can take with them” (Piglia p. 163)

‘Don’t give in, Marquitos,’ said the Kid. He called him by his name for the first time in a long while, in its diminutive form, as if the Gaucho were the one in need of consolation. Then the Kid raised himself up ever so slightly, leaning on one elbow, and murmured something into his ear which no one could hear, a few words of love, no doubt, uttered under his breath or perhaps left unuttered, but sensed by the Gaucho who kissed the Kid as he departed” (Piglia p. 181)

‘Don’t give in, Marquitos,’ said the Kid. He called him by his name for the first time in a long while, in its diminutive form, as if the Gaucho were the one in need of consolation. Then the Kid raised himself up ever so slightly, leaning on one elbow, and murmured something into his ear which no one could hear, a few words of love, no doubt, uttered under his breath or perhaps left unuttered, but sensed by the Gaucho who kissed the Kid as he departed” (Piglia p. 181)

“Ready to doe, no way; because nobody’s ever ready to die, but prepared to die, yes” (Piglia p. 183)

“And the Gaucho could feel him there, dead at his feet, the only man who had ever loved him, and who’d treated him as a person, better than a brother, that Kid Brignone had treated him like a woman, understanding whatever it was he couldn’t bring himself to say and so always saying, he the kid himself, whatever it was the Gaucho felt without being able to express it, as if reading his thoughts” (Piglia p. 188-189)

“The desire for vengeance, which is perhaps the first spark in the electric shock of the human mind when it is cut into, coursed rapidly around the circuit of the crowd” (Piglia p. 202)

“My mother always knew that I was destined to be misunderstood and nobody has ever understood me, but occasionally I’ve succeeded in getting someone to love me” (Piglia p. 203)

It will never be said that I am not the number one Money to Burn defender

The Official “Gabby” Rank List is as follows:

- Money To Burn (controversial take, get over it)

- Death with Interruptions (Me and Death besties)

- The Shrouded Woman (What if I were to die…twice?)

- The Hour of the Star

- My Brilliant Friend (What if I made a perfect shoe? Does that mean I can drop out of school?)

- The Time of the Doves (Someone get these damn birds out of my house)

- Agostino (he isn’t in love with his mom, god)

- Deep Rivers

- The Lover

- “Combray”

- Nadja (It’s giving Breton is a psychopath)

Discussion Question

For those who are not fans, why do you really dislike Money to Burn? Are you afraid of the masterpiece in literature?

For those who are unwavering Money-to-Burnies (our fan club name), what makes this book so unique?

That’s pretty much it. I hope that everyone enjoyed my memes and perhaps changed their tune about the most tragic queer love story in the history of criminals.

“for it is not the same thing to bury a human being and to carry it to its final resting place a cat or a canary, or indeed a circus elephant or a bathtub crocodile…” (18).

“for it is not the same thing to bury a human being and to carry it to its final resting place a cat or a canary, or indeed a circus elephant or a bathtub crocodile…” (18).

If one is to delve deeper into these imageries, you would find references to pigeons. When saying Colometa, “pigeon girl” is expressed in English. The external proof to this comes from an article entitled”Life in Barcelona” by Micheal Eaude. Eaude presents the real world connection to the novel with Plaça del Diamant– a real life place and the original name of the book. The story is reflective of the Spanish Civil War, seemingly entangled with our real narratives. In Barcelona, there is a statue that so similar to Nataila’s story. Sitting in this square is “a low, black sculpture of a naked woman screaming—in anguish or perhaps liberation. She is surrounded by pigeons” (Eaude).

If one is to delve deeper into these imageries, you would find references to pigeons. When saying Colometa, “pigeon girl” is expressed in English. The external proof to this comes from an article entitled”Life in Barcelona” by Micheal Eaude. Eaude presents the real world connection to the novel with Plaça del Diamant– a real life place and the original name of the book. The story is reflective of the Spanish Civil War, seemingly entangled with our real narratives. In Barcelona, there is a statue that so similar to Nataila’s story. Sitting in this square is “a low, black sculpture of a naked woman screaming—in anguish or perhaps liberation. She is surrounded by pigeons” (Eaude).