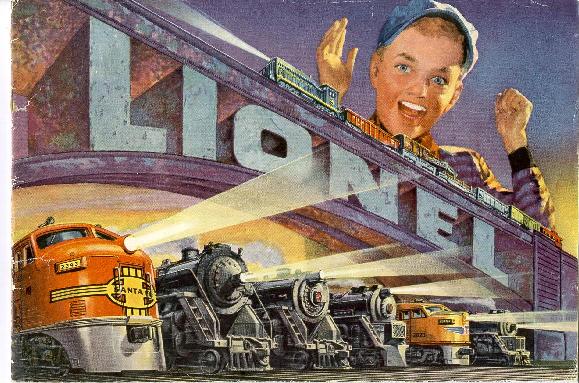

In looking at the passage from Green Grass Running Water from 258-270 (263-274 in my edition), many historical references can be derived from the two stories. In particular, I would like to look at the symbolism in Lionel, his sister Latisha and George Morningstar. To begin, the story of Lionel offers an interesting revelation of Lionel as a forty year old man, following intentional word selection that leads the viewer into believing he is perhaps child. Words such as; insect, “click click click”, colour, black, sound, and a display of hopelessness lead to an evocation of childhood. The final evocation of this is a “happy birthday” which is met is immediately met with the revelation that Lionel is, in fact, forty on this day. The name Lionel itself seems to be in reference to the toy train company, which is based in George Morningstar’s “home” Michigan.  As he discusses what he wished to be as a child, he discusses career possibilities while referencing a hart topping single in the 1940’s from Betty Hutton, ‘Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief’. Hutton’s birthplace is, you guessed it, Michigan.

As he discusses what he wished to be as a child, he discusses career possibilities while referencing a hart topping single in the 1940’s from Betty Hutton, ‘Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief’. Hutton’s birthplace is, you guessed it, Michigan.

In revealing a childhood wish to be John Wayne, Jane Flick describes this as signalling a self hatred of “indianness”. As Native Americans picketed his shows for being a “Injun-hating” character, no other explanation could be offered.

Taking this further unto the next portion of the chapter, King introduces John Wayne’s outfit as a allusion to George Morningstar’s (George Custer’s) wartime attire (Flick).

“LOOKS A LOT LIKE MY JACKET.” . . . . “YES,” SAID THE LONE RANGER. “IT’S YOUR JACKET ALL RIGHT.” “IF YOU LOOK CLOSELY” SAID ISHMAEL, “YOU CAN TELL.”

Here Flick offers this passage as a direct link between George Morningstar and General Custer. Custer himself was also given the nickname “son of the morning star” by plains Indians.

The character of Latisha is presented as a contradiction to the stereotype, of a “stock image of a Native woman on Welfare” (Knopf 264). She is portrayed as a successful businesswoman, and loving mother to her three children in stark contrast to that idea. The name of Latisha’s business, Dead Dog Cafe, is too alluding to a stereotype of “dog meat” being a part of Native cuisine. “It’s a treaty right, there’s nothing wrong with it. It’s one of our traditional foods.” While the food is merely beef, it serves as a refrain of King’s attempt to dispel inaccuracies and inequities in Native perceptions in the general public. Ironically (or intentionally by King), Custer wrote a novel in 1872, My Life on the Plains, which featured American’s eating dog meat at a Native ceremony, and after spitting it out (Mardsden 262). The character of Latisha, the cafe, and the family all serve to further King’s attempt at quashing the stereotypes which pervade modern Canadian society and Literature. In fact, King found this so profound that he launched a CBC radio show by the same name a the cafe, which ran for four seasons in the late 90’s.

For those class members who may have asked why it is we are reading this, here is an example of the general scholarly consensus who mimic Professor Patterson as to the importance of this work:

The fiction of Thomas King has been instrumental in breakin up dominant stereotypes of the “Indian” in mainstream Canadian literary history. There is no doubt that King has managed to modernize the image of the Native. (Knopf)

Citations

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Wate.”Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999): 140-172. Print.

Kendall, Mary Claire. “Betty Hutton’s Miraculous Recovery.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 11 Mar. 2013. Web. 21 July 2014.

Knopf, K. Aboriginal Canada Revisited. 2008. University of Ottawa Press

Marsden, P.H. Towards a Transcultural Future: Literature and Human Rights in a ‘post’-colonial World. Rodopi, 2004

Paterson, Erika. “Student Blogs.” English 470A Canadian Studies Canadian Literary Genre 98A May 2014. UBC Blogs, 2014. Web. 17 Jul 2014.

Media:

Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web.<http://wd4eui.com/Pictures/Toy_train_1952_cat.jpg>

“Betty Hutton in “Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief” Number.” YouTube. YouTube, n.d. Web. 21 July 2014.