Milan, the second largest city in Italy (next to the capital Rome), has an area of 181.76km2 and a population of 1.35 million people[1]. It is the top fashion city in the world as well as a major financial and business center in both EU and the world[2]. It also has the top level of cars per capita (car concentration) in the world, which was reported as 0.6 cars per resident[3] in 2011, according to the study by Rotarisa et al. With that being said, it is not hard to imagine, Milan is one of the most polluted and most congested cities in the world.

Political Origin and Objectives of Area C Congestion Pricing Scheme

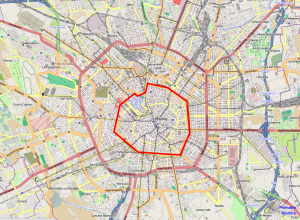

In Jan. 2008, the administration under Mayor Mrs. Letizia Moratti introduced the Ecopass pollution pricing scheme to help curb pollution in the city. It set up the 8.2km2 restricted zone in the city center of Milan (the busiest area in the city) where vehicles need to pay a fee to enter between 7:30am and 7:30pm daily. Different types of vehicles pay a different charge, etc. [4]. According to Rotarisa et al., over the 3 years implementation of the Ecopass scheme, the air pollution had been reduced but the benefits appeared to be diminishing and came to be exhausted[3]. On the hand, Mayor Mrs. Moratti failed to be be reelected in 2011. Mr. Giuliano Pisapia, in June. 2011, became the new Mayor of Milan and needed to decide whether to extend Ecopass, replace it or change it some way. In the referendum around the same time period, 80% votes went to support converting the Ecopass pollution scheme to a more strict congestion scheme[5]. Thus, the congestion pricing scheme Area C came into effect in Jan. 2012 in Milan to replace Ecopass[6]. The Area C scheme has the following aims:

- Tackle congestion issues directly by reducing vehicle access to the city and improving public transit networks.

- Reduce pollution caused by traffic.

- Improve sustainable travel modes[5].

- Overall, improve the life quality of those who have activities associated with the city[7].

How does Area C work?

The Area C congestion pricing scheme is designated for the same area under Ecopass. To enter this 8.2km2 zone of the city center of Milan on the weekdays between 7:30am – 7:30pm (Thursdays’ changed to 7:30am – 6:00pm, since Sep. 2012 )[6]:

Source: Wikipedia

- Vehicles (with exceptions) are entitled for a flat fee of €5.

- Vehicles that belong to the residents inside the area have 40 free entries annually and a flat fee of €2 after that. These vehicles must be registered.

- Some types of vehicles are banned in this area, that include those with emissions at Euro level 0, gas engine, and Euro levels 0,1,2,3, diesel engine. According the the EU emission standards, those high polluting vehicles[8].

- Public transportation are free to enter which includes buses, emergency vehicles, taxis.

- Hybrid, bi-fueled vehicles and scooters are free to enter.

The entrance tickets can be purchased by cash, debit or credit from various locations like meters, retailers, etc. They need be purchased and activated on the same day before entry. Upon entry, the surveillance cameras at the access point will be able to identify the classification of the vehicles and the due charges[7].

The entire system seem pretty smart and the registration for resident vehicles is key to distinguish between the non-resident and resident vehicles. However, for residents, it might provide incentives for those who didn’t often use vehicles to drive in order to use up the free entries since they are free or use the free entries to give rides to non-residents for profits or not. On the other hand, the lower income residents who use vehicles often would be affected the most considering that they would have taken public transit which costs less, if not for a particular reason to use vehicles.

Although there’s no study publicly available to explain how the 40 free entries were decided, the government of Milan probably did research on it. A follow up study to assess the usage of the 40 free entries for resident might be worthwhile in improving the policy in the future.

Also, for allowing hybrid and bio fueled vehicles free access seems to be only on the consideration of pollution reduction. It will create incentives for people to switch to those types of exempted vehicles and at the end the number of vehicles accessing the city center will rebound.

Results after one year of implementation

According to official estimates reported by XinHua,China in Feb. 2013, the Area C scheme in the one year time “caused a reduction by more than 30 percent of vehicles inside the designated restricted zone and 7 percent outside it”[9]. In terms of pollution reduction, “PM10 and NOx emissions [were reduced by] 18% and CO2 emissions [were reduced by] by 35%”, according to a recent study[10]. The study also indicates that Area C has raised €20.3 million for the public transport investment funds and the bike sharing system. The funds then can be used to further improve the public transit and improve infrastructure to make biking a safer and more feasible way of transportation. Although the lower income group don’t directly benefit from the scheme, they will be benefited as the transit net work improves, since they are probably the most frequent users.

Conclusion

Overall, the Area C through the charge to reduce the number of vehicles accessing the city center of Milan could be more effective and more lasting if the there’s no exemption on the hybrid or the bio fueled vehicles. This policy can work more effectively by focusing on one main goal which is the reduce congestion. For pollution reduction, it should be addressed by a separated policy or scheme independent of Area C.

1. Wikipedia. (2013, Mar.). Milan. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milan

2. Wikepedia. (2013, Mar.). Economy of Milan. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Milan

3. Danielisa,Romeo. Rotarisa, Lucia. Marcuccib, Edoardo. and Massianic, Jérôme. (2011, Nov.). An economic, environmental and transport evaluation of the Ecopass scheme in Milan: three years later. Retrieved from http://www2.units.it/danielis/wp/Ecopass%20-%203%20years%20later,%20finale.pdf

4. Wikipedia. (2013,Mar.). Ecopass. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecopass

5. Di Bartolo, Caterina. (2012, Nov.). AREA C in Milan: from pollution charge to congestion charge (Italy). Retrieved from http://www.eltis.org/index.php?id=13&study_id=3632

6. Wikipedia. (2013, Feb.). Milan Area C. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milan_Area_C

7. Commu di Milano. (n.d.). Area C. Retrieved from

8. Desiel Net. (2012, Sep.). EU Cars and Light Truks. Retrieved from http://www.dieselnet.com/standards/eu/ld.php

9. XinHua, China.org.cn. (2013, Feb.).Feature: The decade for Milan air pollution control. Retrieved from http://www.china.org.cn/world/Off_the_Wire/2013-02/01/content_27854057.htm

10 . CASCADE project. (2013, Mar.). Milan hosts first CASCADE study visit. Retrieved from http://www.eurocities.eu/eurocities/news/Milan-hosts-first-CASCADE-study-visit-WSPO-95RCLA