The Doctrine of Discovery

The treatment of the Cherokee and their land by European settlers was informed by what is known as the Doctrine of Discovery. This perspective is based on the notion that Christian settlers and missionaries have a divine right to land that was “discovered”, such as North America, regardless of the peoples who lived there previously. There are three interpretations of this premise that were supported during different periods of time in American history. The most extreme, the absolute definition, asserts that the European conquest of America gives the settlers all the rights and legal title to the land inhabited by Indigenous peoples. The second interpretation, the expansive definition, states that Indigenous peoples did posses and occupy American land at the time of “discovery”, however they are incompetent and unable to manage the responsibilities of the land and resources. The third and supposedly most common interpretation in the precolonial era, the preemptive definition, recognizes that Indigenous peoples own the land in America, and if they choose to sell any of it the European settlers have the right to purchasing it first. This framework was present until 1801 when American expansionist ideals proliferated, and the treatment of Indigenous peoples as sovereign began to decline (Johansen 208-210).

Interaction and Impact

Prior to the colonial influence of European settlers, the Cherokee lived in multiple villages, each with two chiefs and a village council. Contrary to the incorrect and negative stereotypical portrayal of “uncivilized” American Indigenous populations, the Cherokee lived in permanent settlements that consisted of single or two-story wood cabins. The band relied on the extensive farming of crops such as corn, beans and squash, and also hunted game as well as gathering fruits and nuts. In 1760 the Cherokee waged war on the British over recurring unfair trade, and were able to hold off the armies for two years. In the end a peace treaty was signed by both parties, however the Cherokee lost significant land as a result of both the scorched-earth policy and the aforementioned agreement.

During the War of Independence the Cherokee supported the British army. In 1794 they were forced out of Tennessee and relocated to Arkansas and Texas. Settlers considered the Cherokee one of the Five Civilized Tribes because they adopted Western culture of dress, agriculture and government. In 1821 Cherokee was transcribed into a written language; this significant development along with growing tension between the band and the Europeans can be seen as catalysts for the creation of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Indigenous newspaper. In 1827 the Cherokee officially became a sovereign nation, and began to negotiate various treaties with the government over their land and rights. The presence of democracy, Western institutions, and a written constitution notably altered and disempowered the role of women in this once matrilineal society, where women previously held positions of leadership as chiefs (Johansen 1212-1214).

Applications

This background information on the way European settlers viewed the Cherokee can inform our understanding of the history and dynamic between the two groups. In the Cherokee Memorials there are various references to the ways that the British treated the Cherokee. The Doctrine of Discovery tells us that the perspective of the settlers changed across time. This is reflected in the the Cherokee Memorials with weighted language that speaks of their changing relationship, such as the use of brothers to address the court and European population at large, versus the latter use of children to refer to the Cherokee and fathers to refer to the Europeans. The history of colonialism and the impact Western influence had on the Cherokee can also help us to understand the references made in the Cherokee Memorials to the treaties discussed. The speaker mentions the sovereignty and independence the Cherokee once had, and this context gives us a background on how that came to be.

References:

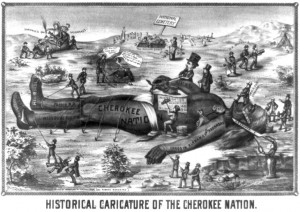

Mintz, S., & McNeil, S. Historical Caricature of the Cherokee Nation. 2013. Digital History. Web. 21 March 2014.<http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/indian_removal/cartoon1.cfm>

Pritzker, Barry and Bruce E Johansen. “Cherokee.” Encyclopedia of American Indian History, 2008. Web. 21 March 2014.

Pritzker, Barry and Bruce E Johansen. “Doctrine of Discovery.” Encyclopedia of American Indian History, 2008. Web. 21 March 2014.