The various allusions King weaves together throughout pages 126 – 136 create themes around power and control, and Indian stereotypes. For beyond the cheery and humorous storytelling is a dark and unsettling story of dominance, sexism, and racism.

The first of the two chapters takes place in Bill Bursom’s Home Entertainment Barn with the focus being on what Bill calls The Map. The tone of disrespect and domination is set immediately in the chapter when Bill doesn’t know how to address his employee properly, and responds with her correction with “Whatever.” He also assumes moral and intellectual superiority over her when his dismisses her as not being able to understand the “unifying metaphor” and the “cultural impact” of The Map.

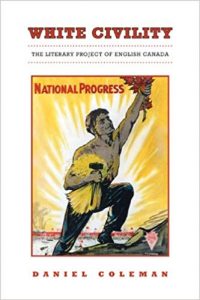

Bill himself represents an oppressive force to Natives. His name is a combination of the names of two men known for their hostility towards Indians (22). Holm O. Bursum advocated for New Mexico’s mining resources at the expense of the Pueblos. There is a parallel between Bill creating The Map, and Holm having “his eye on the map of New Mexico…which aimed to divest Pueblos of a large portion of their lands and to give land title and water rights to non-Indians” (22). The “Buffalo Bill” part of his name alludes to William R. Cody who was known for exploiting Natives in his plays. Thus, Bill Bursom has links to individuals who oppressed and dominated Natives, with the latter also contributing to creating Indian stereotypes.

Bill oppresses Natives by selling televisions. Throughout the novel, television and t.v. watching is used like alcohol to Native people. It draws them into a false reality that they use to escape from the hardships they face. Lionel, Amos, and many other Natives in the novel resort to television when life becomes unbearable. It produces tropes of stereotyped Natives being dominated by whites. And behind the scenes of these movies and shows is a world that exploits and humiliates Natives like Portland. Finally, television is a defining thread in the capitalistic, materialistic, Western web that is antagonistic to the Native way of life.

Bill sees himself as a Machiavellian prince. He will unapologetically exploit Natives because they are a potential threat to stable Western culture and government. Like a Machiavellian prince he cruelly oppresses those who might threaten stability, and his tool of oppression is televisions. This is the “unifying metaphor” of The Map that Lionel and Ms. Smith don’t understand (128). The Map represents a North America that maintains power and control over internal dissent by television. Thus, for Bill, the “cultural impact” (128) of television is its use as a tool of oppression.

The next chapter continues expanding on the theme of power and control by narrowing its exchange between Native women and white men, and expands more on the issue of Native stereotypes.

Jeanette, Nelson, Rosemarie De Flor, Bruce are all active in the stereotyping of Canadian Indians (25). Although Jeanette is kind to Latisha, Nelson’s blatant sexual harassment sullies the exchange. He views her as an object and, like George Morningstar, knows she is a “real Indian” (130, 133). Both men dominate Latisha and see her for her Indianness rather than her individuality.

Like Bill, George represents a figure known to be hostile towards Natives, namely George Armstrong Custer (20, 33), who is known as a famous Indian fighter. His glib, spiritually empty character prevents him from seeing past generalizations and stereotypes. Although he appears intelligent and attentive, he really lacks understanding and can’t see anything more than an Indian stereotype.