In The World is Moving Around Me, Dany Lafarriere often makes reference to Port-au-Prince as an artistic capital of the world. He refers to how when everything else falls apart, culture remains. Throughout the book Haitian art is placed within the context of a history of hardships, and in a sense growing out of this history. In the chapter “A City of Art,” he argues for turning “Port-au-Prince into a city of art” within the process of rebuilding (122). Here he sees the an opportunity not to re-write history, but to change the landscape to visually represent what he – as part (or at least he used to be) of the Port-au-Prince artistic circle – sees as such a vital part of Haitian culture. He says “Despite our troubles, our culture is joyful; we need to show it off” (123). The way I see it here, Haitian art is not only about resilience, but also pride in a world that often projects a very one-sided perspective of the country (something he attempts to dispel throughout the text). Frankétienne represents this attempt “to turn this disaster into a work of art” (113), the symbol of the resilient Haiti that continues to grow and does not let itself be shaped by the disaster, but rather use the disaster to shape his own vision. This is cultural creation as agency.

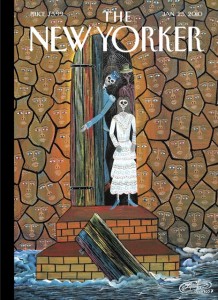

This made me think of the great Haitian surrealist painter Frantz Zepherin, who has made beautiful paintings of Haiti after the earthquake. Here is a good article on his art and a US exhibit in 2010 called “Art and Resilience.” You can find all the paintings from that exhibit online here. One of his paintings was featured on the cover over the New Yorker in 2010, which greatly differs from the Demers’ photograph we saw in TIME. In an article for the Smithsonian, he describes the exigence to paint he felt right after the earthquake hit: “That night, I decided I had to paint…So I took my candle and went to my studio on the beach. I saw a lot of death on the way. I stayed up drinking beer and painting all night. I wanted to paint something for the next generation, so they can know just what I had seen.” The entire article is really worth reading because I think it does a good job at avoiding the disaster clichés of a post-Earthquake journalism by focusing specifically on a couple of painters, their personal stories in their own words, and how they are dealing with the disaster in their own terms. We might want to think of how a more narrow lens (perhaps “more specific” is a better way of explaining it) relates to Lafarriere’s balance of personal narratives within a public event.

Earthquake Timer

Humanitarians and Soldiers

Ground Zero

Interpellation of the Great Spirits for the Saviour of the Country

New Yorker Cover

I really loved Zepherin’s work that you included here, especially the New Yorker cover. It really exemplified to me how art in any context opens up a world far beyond that of “rationality” or “discourse.” A lot of times the only way to expose subconscious modes of expression is to paint, write, etc. Art in all capacities somehow manages to surprise me over and over at communicating ineffable emotions or realities. The fact that Zepherin felt this immediate exigence to paint after the earthquake hit shows how perhaps art is the only way to communicate that which is beyond language or point blank representation. This post to me demonstrates how language and other forms of accepted representative modes really fail where other modes thrive in getting close to the meat of reality.

Hi Sam,

I enjoyed your post on Zepherin, and read the article in the New Yorker. What stands out to me in his paintings more than anything are immediacy present in the pictures, and the perspective from which they were drawn. As it is commented in the New Yorker, the open eyes looking at the viewer have the attachment to life, they are the eyes that have recently died and feels almost as if they can still see and feel the pain. It was also mentioned that Zepherin’s home was very near the epicentre of the earthquake, and it is especially powerful that all the pictures are drawn from the perspective of someone looking outward from the source. Most pictures of the earthquake, and even parts of Laferriere’s narrative, are told from the outside looking inward. By offering the reverse perspective, it leads me to think on the destructive force of a natural disaster in its power to disrupt and sever the continuance of life, whereas images and descriptions from the outside can only purvey the sense of devastation. Looking at the devastation may entice compassion, but doesn’t provide enough context to register the non-physical displacement that was perhaps greater than loss of property.