Bring Your Own Device (BYOD)

“Why are the high school students’ backpacks so much smaller than [the primary students’] backpacks?” This was a question I was asked by one of my 9-year-old students. At the K-12 international IB school I work at in China, students are required to bring their own devices to school when they move up from elementary to secondary. In elementary school, home learning is assigned online through Firefly, while submission can happen digitally or on paper. Once students move on to secondary, they are required to submit their work online through Firefly, check their school email and Microsoft TEAMS learning space for learning materials from their teachers, thus explaining the smaller-sized bags my student observed.

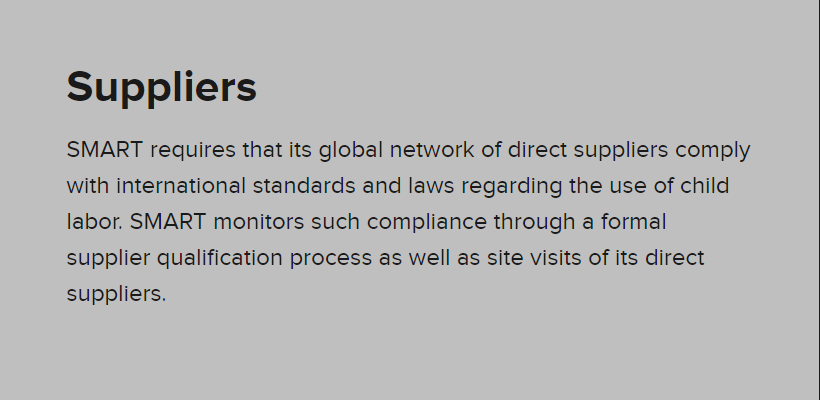

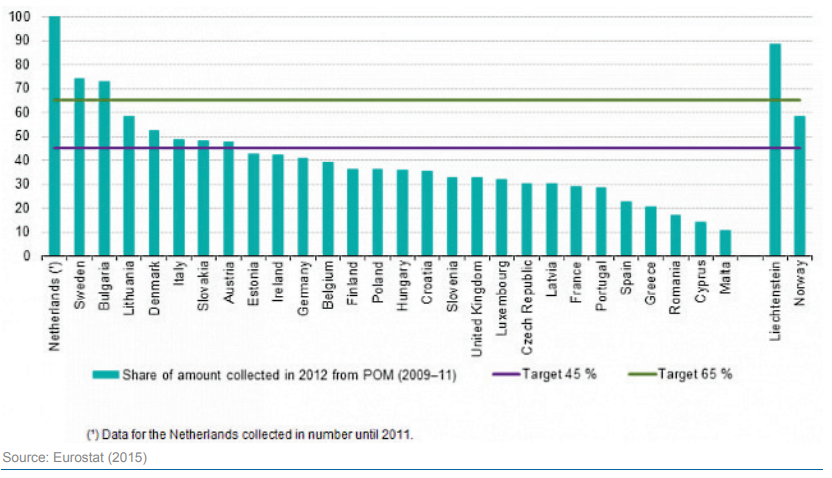

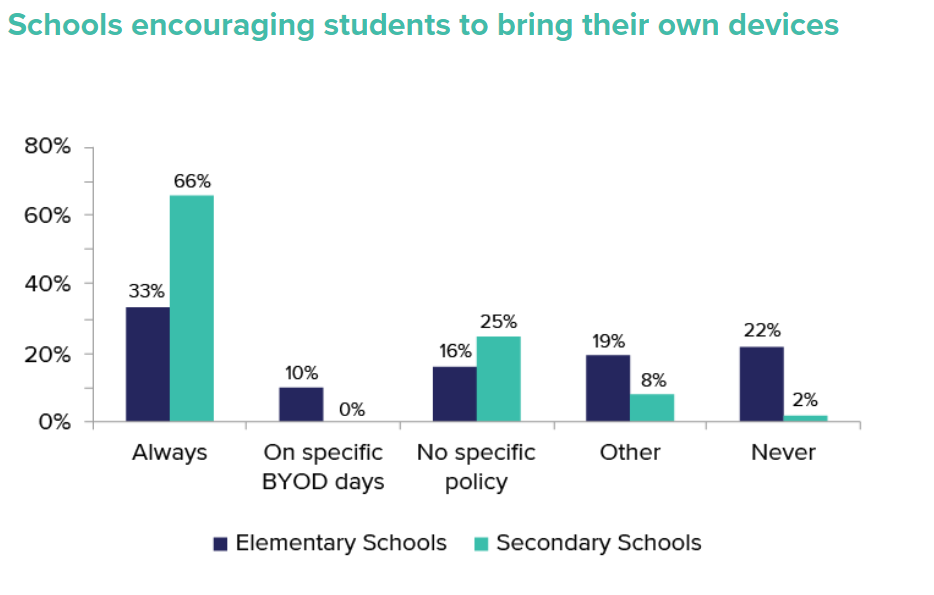

Starting in the last term before entering middle school, Year 6 students and their parents are asked to bring a device. Students who are unable to bring a device to school have access to a school iPad, but during the last school year all Year 6 students were able to bring their own device. I was unable to find numbers related to BYOD in schools within China; however, according to People for Education’s website (2022), the last few years have seen BYOD policies “gaining popularity in education” within the province of Ontario. As seen in Figure 3, there is a greater push towards students bringing their own devices when they move from primary to secondary.

Figure 1

Schools encouraging students to bring their own devices

From People for Education (2019). Connecting to success: Technology in Ontario schools. https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/connecting-to-success-technology-in-ontario-schools/

BYOD policies first started in businesses for sustainability reasons before becoming popular in the education system (Oaks, 2013). The displacement of textbooks and paper brought about by students bringing their devices to school will be examined through the lens of sustainability.

What is sustainability?

[D]evelopment that meets the needs of the

present without compromising the ability

of future generations to meet their own needs.

(Gro Harlem Brundtland, 1987, p. 2)

Save Paper, Save Trees

Oaks (2013) states that BYOD policies are good for the planet. Students’ devices can serve as a “repository for textbooks for the class they are taking or a storehouse for their own reading material. This obviously cuts down on the amount of paper needing to be produced, thereby saving countless trees.” However, a 2016 study conducted by an environmental think-tank specializing in forestry research and analysis, Dovetail Partners, found that while the decrease in American paper production has led to a decrease in the number of trees used to make paper, it has not led to more trees in American forests (Dovetail Partners, 2016). The Dovetail Partners (2016) paper noted that there has been a decrease in paper production since the 90’s–in 2013 down 15% from 2007 and 20% from 1995, but production has shifted to Asia, so why has there not been a significant change in the number of trees saved in the USA? Traditionally, paper was primarily created from sawdust and woodchips, which as lumber by-products (Dovetail Partners, 2016). Since the late 1990s there has been a decrease in constructing houses, which has created a decrease in lumber by-products, resulting in an increase in trees harvested for paper production (Dovetail Parnters, 2016). Dovetail Partners (2016) outlines a concern that public policies may cause forests to be converted into commercial sites because most wood products in the United States come from privately-owned land. If there is no demand for wood products, these landowners may clear their lands in favour of a more profitable endeavour (Dovetail Partners, 2016).

Figure 2

Permitted Electronic Communication Devices

From Leman International School, (2022). Primary BYOD presentation for parents and students 2021-22 .

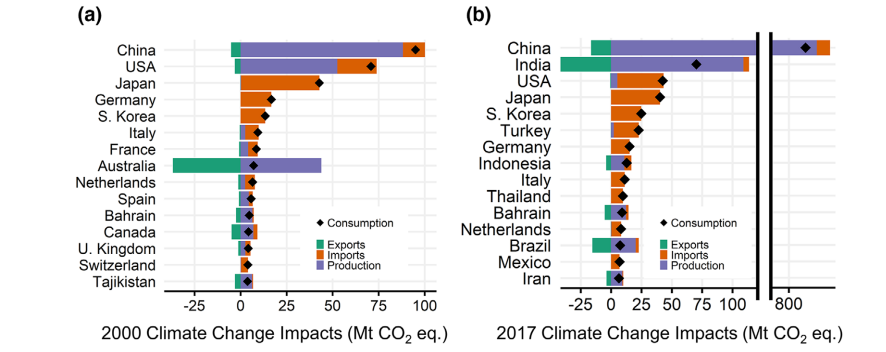

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

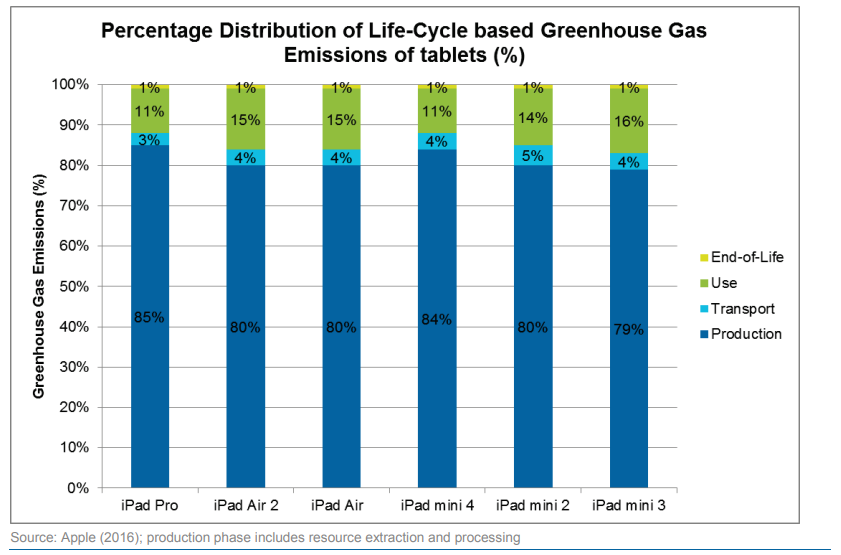

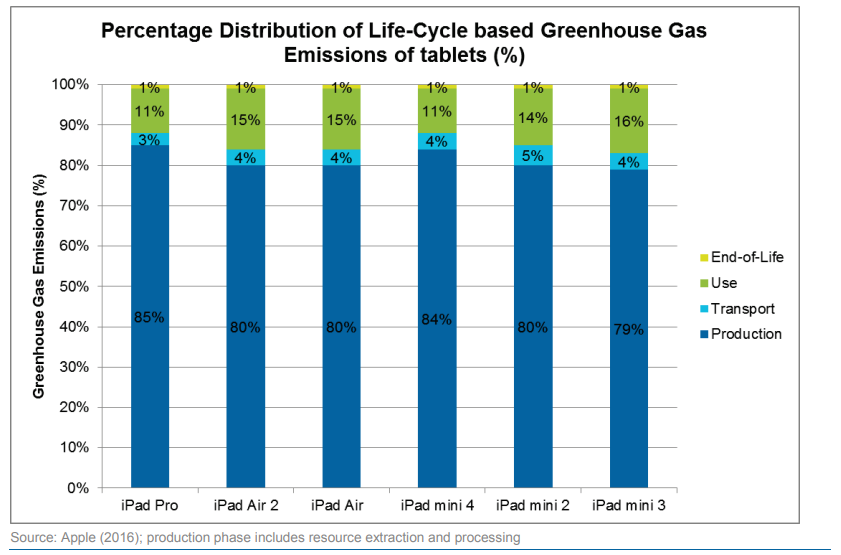

Zooming out from the trees to see the forest, there is a global ecosystem affected by BYOD. The two products recommended to students at my school are the Apple iPad and the Chromebook, so this paper will compare these two products. Apple and Google have both made public their efforts to be sustainable. Apple’s website declaring it has been carbon neutral since 2020 and by 2030 their products will be as well and Google has been carbon neutral since 2007, in 2017 it was the first company to match 100% of its annual electricity consumption with renewable energy and in 2030 all its data centers and campuses will be running on carbon-free energy (Alcorn, 2021). Using Apple’s data, Greenpeace’s Resource Efficiency (Manhart et al., 2016) in the ICT Sector report shows that during the average iPad’s lifetime, more than three-quarters of greenhouse gas emissions happen during the production stage. This is due to the 2-3 year lifespan of tablets (Manhart et al., 2016), which falls short of some state school funding policies that require devices to last at least 4 years in Australia and New Zealand (Sweeny, 2012). Notebooks on the other hand, have a lifespan of 5 years. New Chromebooks could potentially last for 8 years with Google’s promise to provide at least 8 years of updates (Alcorn, 2021), lessening its environmental impact.

Figure 3

Percentage Distribution of Life-Cycle based Greenhouse Gas Emissions of tablets

From Manhart, A., Blepp, M., Fischer, C., Graulich, K., Prakash, S., Priess, R., Schleicher, T., & Tür, M. (2016, November). Resource efficiency in the ICT sector. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.de/sites/default/files/publications/20161109_oeko_resource_efficency_final_full-report.pdf

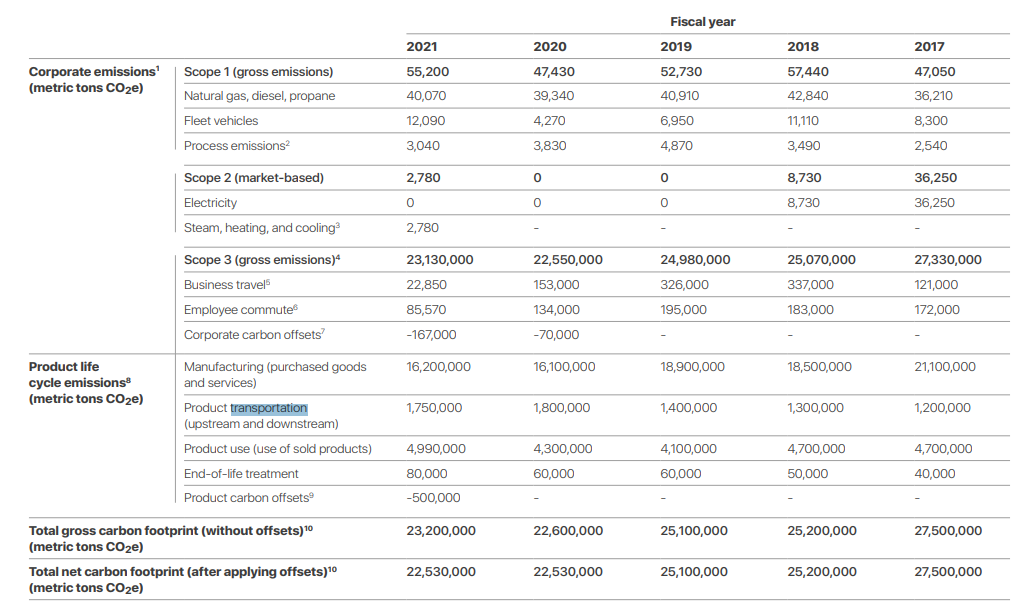

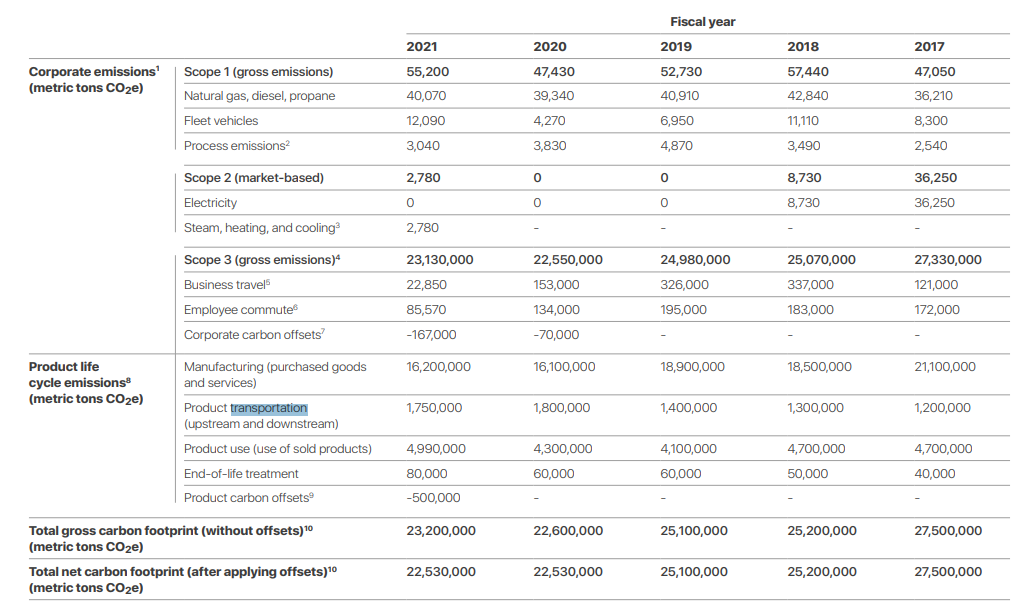

Figure 4

Greenhouse Emissions for the Apple Company

From Apple Inc. (2022a). Environmental progress report. https://www.apple.com/environment/pdf/Apple_Environmental_Progress_Report_2022.pdf

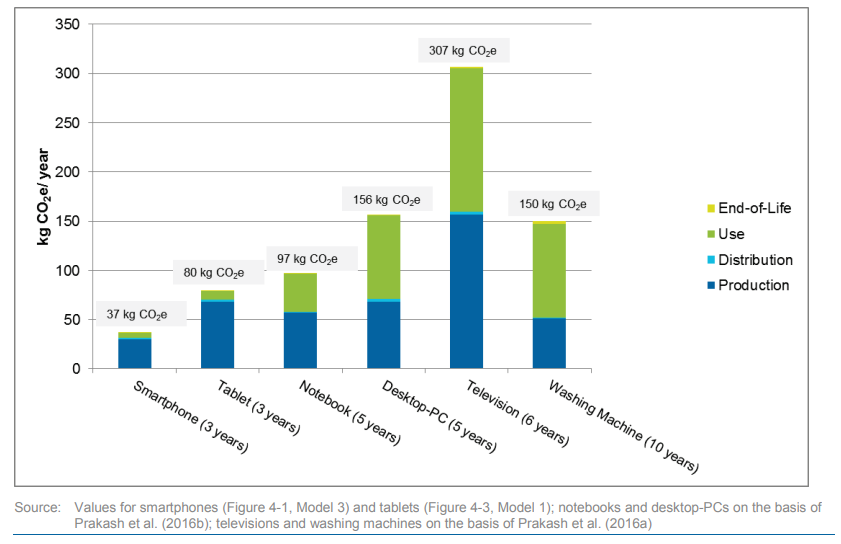

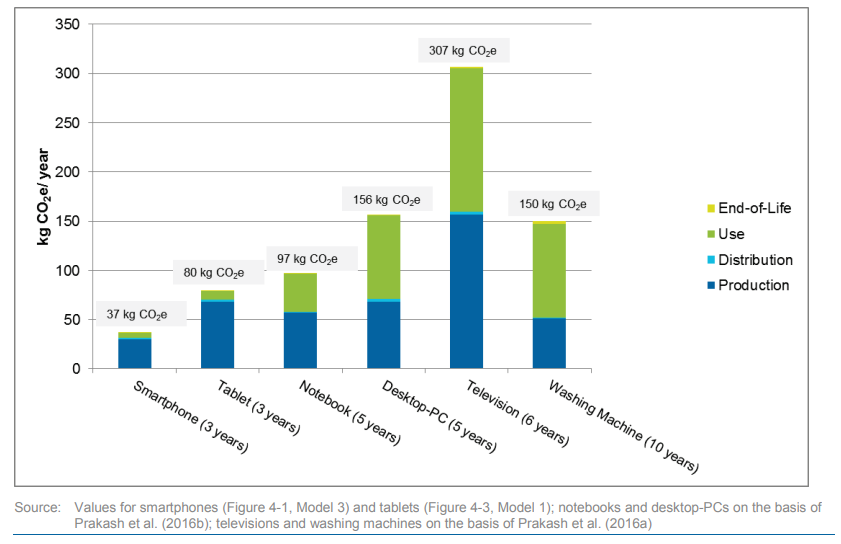

Emissions for Chromebooks were not available specifically, but data for notebooks show lower emissions over tablets when comparing them through an emission per year calculation: tablets at 26.7/year and notebooks at 19.4/year.

Figure 5

Comparison of annual greenhouse gas emissions (kg CO2e/year) of various products

From Manhart, A., Blepp, M., Fischer, C., Graulich, K., Prakash, S., Priess, R., Schleicher, T., & Tür, M. (2016, November). Resource efficiency in the ICT sector. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.de/sites/default/files/publications/20161109_oeko_resource_efficency_final_full-report.pdf

To the Cloud

The Chrome OS utilizes a cloud platform and can be paired with CloudReady to run on both PC and Mac devices (Alcorn, 2021). CloudReady is highly accessible and capable of speedily reusing existing hardware for both new devices and older devices such as a 7-year-old laptop (Alcorn, 2021). Not having to replace existing devices is a way to minimize electronic waste.

Packaging

Another sustainability measure Apple has taken is a reduction in plastic used to package iPads. Packaging for iPads consists of 92% fiber–45% of which is from recycled sources (Apple, 2021). The remaining fiber comes from virgin wood from “responsibly managed forests” (Apple, 2021, p. 5). According to Apple’s Sustainable Fiber Specifications, they do not accept fibers from illegal sources; sources must be certified from a list of Apple-approved sustainable management or sourcing programs (Apple, 2016). Apple requires its suppliers to provide documentation proving they meet its Sustainable Fiber Specifications within 24 hours of demand, but the document does not indicate that Apple performs regular checks on suppliers (Apple, 2016). The responsibility to maintain specifications after initial approval lies on the suppliers. This allocation of the burden of responsibility is also applied to Apple’s approach to ensuring fair treatment of workers in factories and mines.

Chromebooks are devices that use a Chrome OS, so devices are created by a multitude of companies. Alcorn (2021) notes that the first Chromebook made with ocean-bound plastics was created by HP and Acer’s Chromebooks use 60% less PCR and virgin plastics.

Human Rights in Factories

The Apple Supplier Responsibility Standards is a document that explains Apple’s expectations for suppliers regarding human rights. It is a multi-page document that lists what the supplier must do, rather than what Apple will do. Suppliers are expected to keep relevant records proving they have upheld these standards and are asked to provide these documents immediately upon request from Apple (Apple, 2020). Apple does not take an active role in ensuring these standards are met and documentation recorded appropriately, for example, “[i]f any Active Underage Worker, Historical Underage Worker, or Terminated Underage Worker is found either through an external audit or self-review, Supplier shall notify Apple immediately and shall implement a remediation program as directed by Apple” (Apple, 2020, p. 19).

A Google search using the terms “Apple” and “factory workers” shows reports from 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 of labour law breaches in Apple’s suppliers’ factories in China and India. Foxconn is mentioned in three of these four reports. While inaccurate reports such as Mike Daisey’s visit to a Foxconn factory (This American Life, 2012) do occur, it is concerning that there continue to be negative reports surrounding one of Apple’s major suppliers, Foxconn.

When the Google search was replaced with “Google” and “factory workers”, articles revealing Google illegally underpaying its workers appeared. The Guardian reports that since May 2019, Google has known that it was in violation of local laws in the UK, Europe and Asia requiring temporary workers to be paid the same amount as full-time workers for the same work, but took two years to comply (Wong, 2021).

Rare Earth Minerals

While Apple has been taking measures to reduce its carbon footprint, the company’s contribution to the throw-away culture has to be considered as well. Every year Apple releases new “non-upgradable and non-maintainable” products (Bender, 2021), yet a 2019 report by the Royal Society of Chemistry states that there are 40 million unused devices in the UK and only 18% of users have any intention of recycling them in the future (cited in Cawley, 2019). Despite global numbers not being available, estimates from different studies suggest that at the most less than 50% of mobile devices are recycled, though the number is likely to be less than 20% (Chancerel, 2010; Geyer & Blass, 2010; Hagelüken, 2006 cited in Manhart et al., 2016, p. 40).

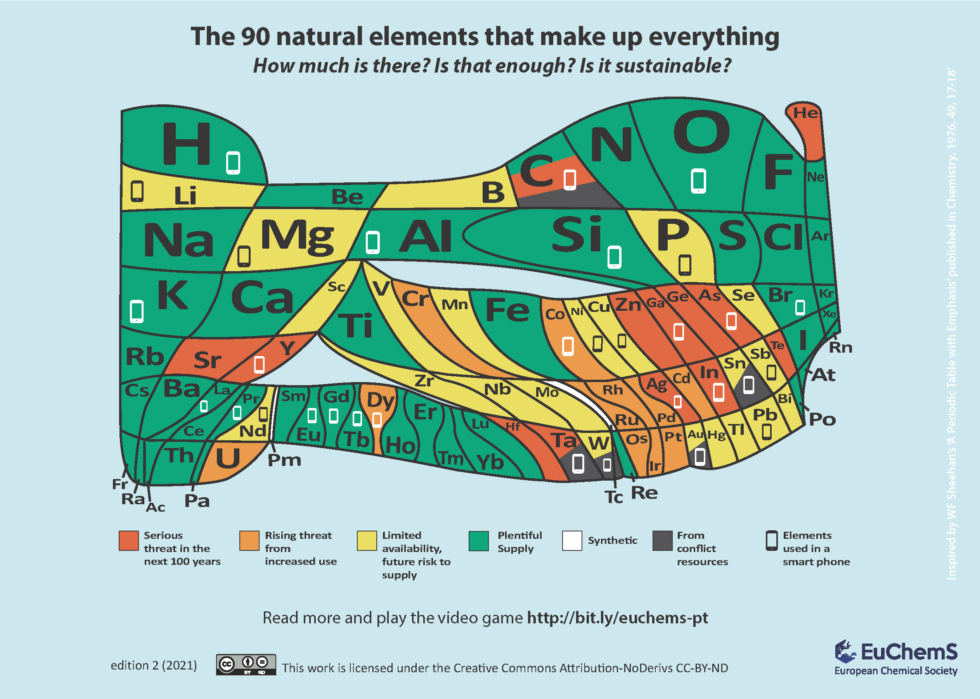

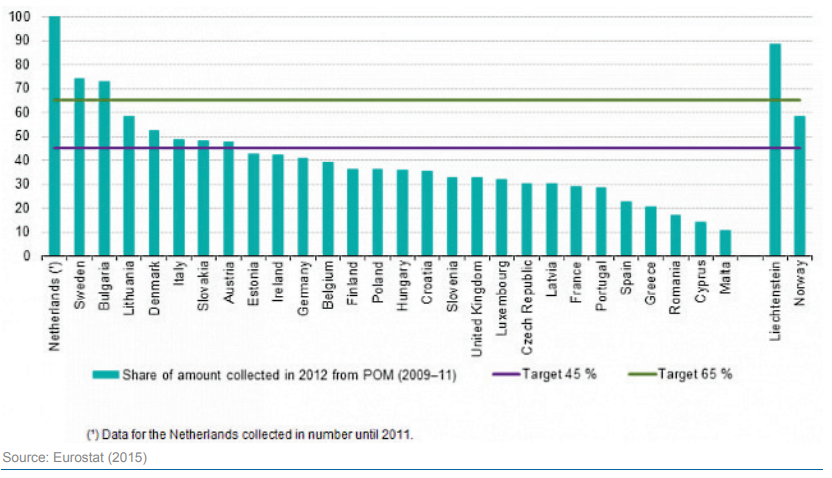

Figure 6

Collection Rate of Waste Electricals and Electronic Equipment in Europe, 2012

From Manhart, A., Blepp, M., Fischer, C., Graulich, K., Prakash, S., Priess, R., Schleicher, T., & Tür, M. (2016, November). Resource efficiency in the ICT sector. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.de/sites/default/files/publications/20161109_oeko_resource_efficency_final_full-report.pdf

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

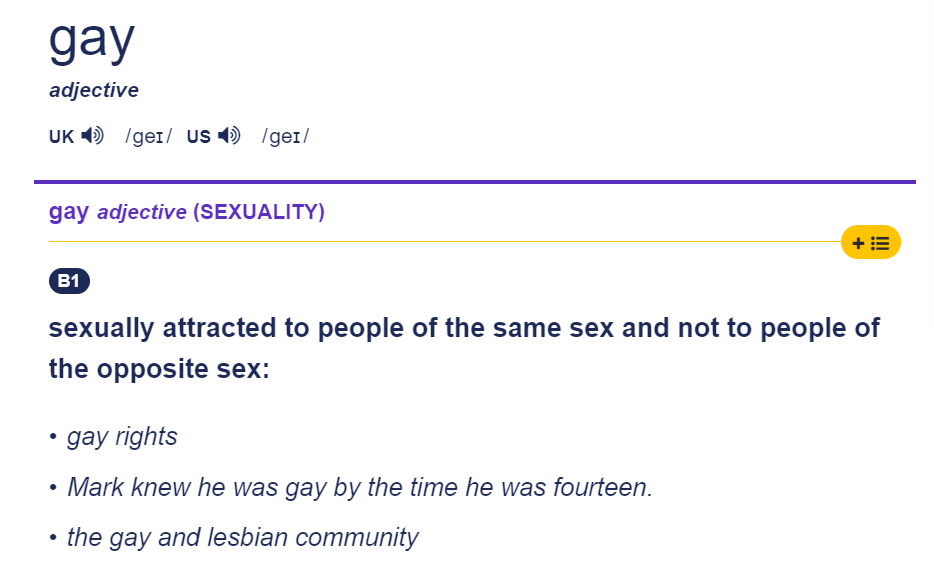

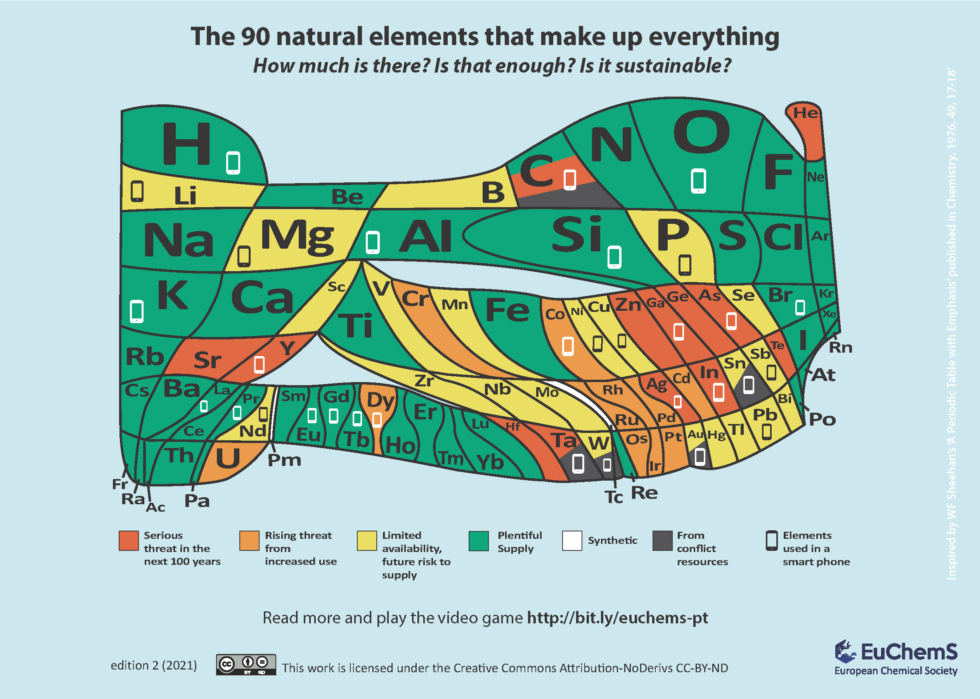

Cawley (2019) goes on to explain that this finding is alarming due to the European Chemical Society’s study indicating that elements used in devices are in danger of disappearing from nature. The rare earth metals Apple’s iPad uses are tin (Sn), tantalum, tungsten (Ta), gold (Au), cobalt (Co), and lithium (Li). 65% of the device’s rare earth minerals are obtained through recycling (Apple, 2021, p. 3). Data from other countries show that unused devices are a widespread problem, according to the figure above, only a few European countries manage to collect 50% or more of their Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (Eurostat, 2015 cited in Manhart et al., 2016). In 2017 Australia, a country of 26 million people had 23 million unused devices and in 2014 the US had $13.4 billion worth of unused devices (Cawley, 2019). To promote recycling, Apple has a Trade-In program that operates in 99% of the countries they sell their products (Apple, 2021, p. 7). Eligible Apple products can be traded in for store credit or an Apple gift card while other devices can be brought in and recycled for free (Apple, 2021, p. 7). Google’s recycling program is also available for any device. People can drop off their devices at a collection site or request a shipping label to ship their device(s) to the nearest recycling plant (Google, 2022).

Figure 7

The 90 natural elements that make up everything

From European Chemical Society, (2021). Element Scarcity. https://www.euchems.eu/euchems-periodic-table/

Apple’s Conflict Minerals Report for 2021 states that the company does not directly purchase minerals from mines, but they require their mineral suppliers to undergo third-party audits. The document does not state how often these audits occur, but 2021 was the seventh-straight year that all of their suppliers participated in an audit (Apple, 2022b). Despite the use of third-party audits, the report leaves room for questions. Within the report there was mention of human rights but no mention of violence or women. There was also mention of working alongside activist groups, but the numbers and initiatives were not described. Both Buss (2018) and Niarchos (2021) point out that what constitutes sexual violence or human rights abuse is unclear or misrepresented. Niarchos (2021) shares that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, having sexual intercourse with a virgin can increase a man’s luck in the mines which has led to the rape of children often resulting in the death of the children. This belief is so widespread and culturally ingrained that it is not always recognized as sexual violence by the locals (Niarchos, 2021). On average families are so poor that children are expected and needed to work for the family’s survival (Niarchos, 2021). Work and possibly die in unsafe working conditions or not work and starve to death. Situations such as these define what could be described as a place between a rock and a hard place.

Conclusion

Despite its flaws, the availibility of data from Apple indicates that Apple has been expending more of its resources toward sustainability compared to its competitors. Both Apple and Google promote their measures to reduce carbon emissions, but data on establishing and maintaining human rights are unclear or not available in detail. While I appreciate the flexibility and range of price points available for Chromebooks and question some of Apple’s business practices (Batterygate), I think Apple products are more sustainable, especially with its Trade In program. Although both companies have recycling programs in place and both do not seem to prioritize marketing these programs, Apple’s Trade In seems more accessible, which was a key factor in my decision because companies need to be responsible for their unused devices. Cities can implement collection programs for Waste Electricals and Electronic Equipment, but the process of sorting materials is time-consuming, costly and difficult when a facility has to process a variety of materials (Mars et al., 2016). When governments and consumers hold companies accountable for the afterlife of their products, more thought and care will be put into designing sustainable devices and promoting sustainable practices such as recycling among its consumers. The visible presence of Apple stores throughout the cities I’ve lived in better facilitates recycling Apple devices whereas Google would require doing an Internet search or an in-store inquiry. The many and various aspects of sustainability can be daunting so bypassing a simple Internet search can help lighten the load of maintaining the planet.

References

Alcorn, Z. (2021, April 23). Contributing to a sustainable future with chrome OS and partners. Chrome Enterprise. https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/chrome-enterprise/contributing-to-a-sustainable-future-with-chrome-os-and-partners

Apple Inc. (2016, April). Sustainable fiber specification: Version c https://www.apple.com/environment/pdf/Apple_Sustainable_Fiber_Specification_April2016.pdf

Apple Inc. (2020, January 1). Apple supplier responsibility standards. https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple-Supplier-Responsible-Standards.pdf

Apple Inc. (2021, September 14). Product environmental report: iPad (9th generation). https://www.apple.com/lae/environment/pdf/products/ipad/iPad_PER_Sept2021.pdf

Apple Inc. (2022a). Environmental progress report. https://www.apple.com/environment/pdf/Apple_Environmental_Progress_Report_2022.pdf

Apple Inc. (2022b, February 9). Conflict minerals disclosure and report, exhibit. https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple-Conflict-Minerals-Report.pdf

Bender, T. (2021, September 21). Apple and sustainability: The good, the bad and the ugly. Cooler Future. https://www.coolerfuture.com/blog/apple-sustainability

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future (Brundtland report). https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/sustainable-development/sustainability-policy/2030agenda/un-_-milestones-in-sustainable-development/1987–brundtland-report.html

Buss, D. (2018). Conflict minerals and sexual violence in central Africa: Troubling research. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 25(4)W, 545-567.

Cawley, C. (2019, August 19). Unused tech piles up while rare earth elements grow scarce. Tech.co. https://tech.co/news/unused-tech-rare-elements-2019-08

Dovetail Parnters. (2016, February 8). Contrary to popular thinking, going paperless does not “save” trees. Two Sides North America Inc. https://twosidesna.org/US/contrary-to-popular-thinking-going-paperless-does-not-save-trees/

European Chemical Society. (2021). Element scarcity. https://www.euchems.eu/euchems-periodic-table/

Google Store Help. (n.d.). Learn about google’s recycling program. https://support.google.com/store/answer/3036017?hl=en

Leman International School, (2022). Primary BYOD presentation for parents and students 2021-22

Manhart, A., Blepp, M., Fischer, C., Graulich, K., Prakash, S., Priess, R., Schleicher, T., & Tür, M. (2016, November). Resource efficiency in the ICT sector. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.de/sites/default/files/publications/20161109_oeko_resource_efficency_final_full-report.pdf

Mars, C., Nafe, C., & Linnell, J. (2016, May). The electronics recycling landscape report. The Sustainability Consortium. https://www.impact.sustainabilityconsortium.org/wp-content/themes/enfold-child/assets/pdf/TSC_Electronics_Recycling_Landscape_Report.pdf

Niarchos, Nicolas. (2021, May 24). The dark side of Congos cobalt rush. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/31/the-dark-side-of-congos-cobalt-rush

Oaks, J. (2013, October 2). Why BYOD is good for people, planet and profit. Triple Pundit. https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2013/why-byod-good-people-planet-and-profit/47456

People for Education. (2019). Connecting to success: Technology in Ontario schools. https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/connecting-to-success-technology-in-ontario-schools/

Sweeny, J. (2012, November). BYOD in education: A report for Australia and New Zealand. Intelligent Business Research Services Ltd. https://cpb-ap-se2.wpmucdn.com/global2.vic.edu.au/dist/1/30307/files/2013/07/BYOD_DELL-2dtch9k.pdf

This American Life. (2012, March 16). Retraction. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/460/retraction

Wong, J. C. (2021, September 10). Revealed: Google illegally underpaid thousands of workers across dozens of countries. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/sep/10/google-underpaid-workers-illegal-pay-disparity-documents