Preventing ship strikes to whales in the Santa Barbara Channel

In our world, where everyday the news is full of stories of human induced harm and destruction to the natural environment, it is easy to believe that there is no hope for the plants and animals that stand in the way of our continued population expansion. But amid the doom and gloom of popular media coverage comes a rarely reported but increasingly common success story in ocean conservation. In 2013, an elegantly simple measure was put in place in the Santa Barbara Channel off the West Coast of the United States to address the increasing problem of whale strikes in the area. This measure mandated the change in the shipping routes through the channel to avoid areas where whales were known to occur in high numbers. The simplicity of this solution is likely a large part of what made it so successful.

Figure 1. The four whale species threatened by ship strikes in the Santa Barbara Channel. A) Blue Whale B) Gray Whale C) Humpback Whale D) Fin Whale. Images from fisheries.noaa.gov.

What is a ship strike?

Unfortunately, a ship strike is exactly what it sounds like: a severe, often fatal collision between a marine vessel and a whale (1). Ship strikes are the largest threat to whales in most high traffic shipping ports such as the Santa Barbara Channel (1). This is not surprising when you compare the difference in size of whales and the commercial ships that transit the area (Figure 2). The whales are so small in comparison that they are often not seen by the ship’s crew, and if they are, it is usually too late, as ships are usually traveling too fast to be able to adjust course, and the whales are too slow to move out of the way (1).

Figure 2. Size comparison of Gray and Blue whales to a commercial shipping vessel. Figure taken from: http://www.sapient-horizons.com/Oceans_Acoustic_Pollution.html

Where in the world?

The Santa Barbara Channel is a 70 nautical mile stretch of water off the California Coast that spans from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Approximately 2,700 ships transit the channel annually, making it one of the busiest waterways in the world (1). As the global population continues to grow and the subsequent demand for international goods increases, this number will continue to rise (1).

/about/map-california-coast-58c6f1493df78c353cbcdbf8.jpg)

Figure 3. Map of the California Coast. The Santa Barbara Channel spans from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Figure from: About Travel: California Coast.

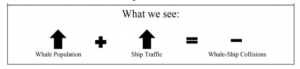

The Santa Barbara Channel is also one of the most biodiverse habitats in the world, providing a home for hundreds of marine plants and animals (1). The high biodiversity in this area is the result of a deep-water upwelling on the edge of an underwater shelf that brings cold, nutrient-rich water from the bottom of the ocean to the surface (Figure 4). This highly productive area attracts species from all levels of the food chain, including some of the world’s largest mammals: blue, fin, humpback and gray whales which utilize the channel both as a feeding ground, as well as a part of their migratory route (2).

Figure 4. Deep water upwelling mechanism. Cold, nutrient-rich water from the bottom of the ocean rises to the surface, providing a food source for a variety of marine species. Figure from: http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/upwelling.html

What changed?

Two major changes were made to the existing shipping lanes into and out of, as well as through the Santa Barbara Channel:

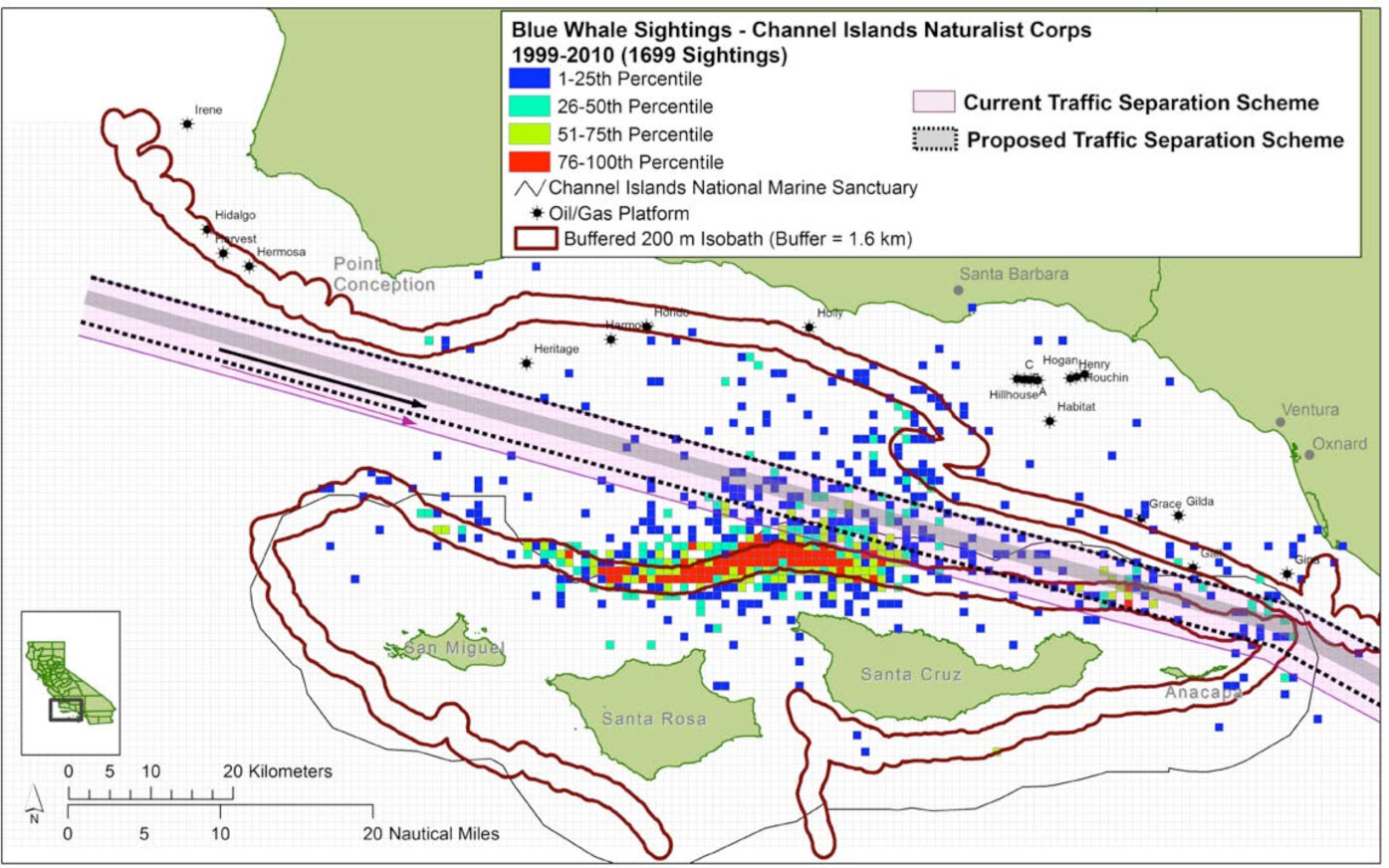

1.As you can see in Figure 5, the southbound lane through the channel was narrowed from the original 2 nautical miles in width, to 1 nautical mile in width to avoid the areas of high whale density (shown in the Figure 5 as red and yellow squares) (3).

Figure 5. Location of endangered whale species and confinement of the southbound shipping lane from 2 nautical miles to 1 nautical mile in width. New lane represented by dotted line. Figure taken from: (CINMS 2016)

2. As you can see in Figure 6, the shipping lanes into and out of the channel were also extended beyond the underwater shelf shown in blue (3). The deep water upwelling along this shelf attracts some of the highest whale densities in the entire channel (1). The extension of the lanes beyond the shelf means that ships can no longer travel directly along the upwelling zone.

Figure 6. Extension of the inbound and outbound lanes of the Santa Barbara Channel beyond the underwater shelf. Figure taken from: (CINMS 2016)

Both of these measures drastically decreased the co-occurrence of at risk-whale species and tanker vessels in the channel.

But wait there’s more!

In 2014 a Voluntary Speed Reduction (VSR) program was put in place in the Santa Barbara Channel in which shipping vessels were given money (up to $2500.00) as an incentive to slow from their cruising speed of about 20 knots to 12 knots or less. This not only reduced the risk of whale strikes but also decreased vessel emissions and improved air quality in the area. A definite win-win! Check out https://www.ourair.org/air-pollution-marine-shipping/ for more info.

So, did this help the whales?

Although these changes to the shipping lanes did not result in an absolute decrease in the number of whale strikes in the channel, there is evidence of a proportional decrease in whale strike occurrences. In recent years, both the amount of vessel traffic through the channel and the size of the humpback, gray, blue and fin whale populations have increased (5). As a result, one would predict an increase in the number of whale strikes. Think of it like this:

However, the number of ship strikes in the channel has remained approximately the same since 2013, meaning that the changes to the shipping lanes and the VSR implementation has prevented an increase in whale strikes from occurring.

That sounds like a success to us!

That’s great for the whales in the Santa Barbara Channel, but what about the whales in rest of the world?

The Santa Barbara Channel whale strike mitigation case is one of the few success stories in the protection of whales against the dangers of commercial shipping. However awareness of the impact of shipping vessels on whales is increasing. The International Whaling Committee (IWC) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) created a list of potential mitigation measures to avoid vessel contact with whales as a user guide for nations trying to tackle this issue in their own waters (6).

As for Canada…

With Canada’s new Oceans Protection Plan, Canadians can hope for a greater commitment to addressing whale strike issues. Some actions stated in this plan include:

- Locating and tracking marine mammals in high vessel traffic areas and relaying information back to mariners

- Responding to marine mammal incidents such as collisions, entanglements and strandings through the best available practices.

- Enhancing enforcement, compliance and surveillance of marine reserves (8).

These measures have the potential to reduce the number of whale strikes in Canadian waters, and also serve as a model to other countries looking to do the same.

You can help too!

You can do your part to help tackle the issue of whale strikes on our coasts here at home. One of the most difficult aspects of this issue is the lack of data on the number of whale strikes that occur because they often go unnoticed by the shipping vessels themselves. If you see a whale strike occur, or a dead or injured whale, please do not hesitate to report it. Through the use of reporting app WhaleAlert, you can easily record, the date, time and location of the strike or of the whale sighting, as well as the species of whale, and a description of its state (7). This information is then sent to the appropriate response agency (depending on your region), and the data is used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for research purposes (7).

Image from WhaleAlert.org

The changes made to the shipping lanes and the additional voluntary vessel speed reduction measures in the Santa Barbara Channel successfully reduced the number of whale strike-related deaths in the region. Looking forward, the continuation of a voluntary speed reduction zone in the channel as well as monitoring whale and shipping behaviour will promote increased protection for whales from shipping vessels. Continuing and improving upon existing mitigation measures on the negative effects of shipping on blue, fin, humpback and grey whales will help protect these and other important marine species.

References:

(1) Bone, J., Meza, E., Mils, K., Rubino, L.L., and Tsukayama, L. (2016) Vessel speed reduction, air pollution, and whale strike tradeoffs in the Santa Barbara Channel Region. Master of Environmental Science Project. Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

(2) Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS) (2016) Ship Strikes http://channelislands.noaa.gov/management/resource/ship_strikes.html (accessed 18 March 2017).

(3) Drake, N. (2013) California shipping lanes moved in attempt to avoid killing whales. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2013/05/whales-and-shipstrikes/ (accessed on 16 February 2017).

(4) Port of Los Angeles (2016) Vessel Speed Reduction Program https://www.portoflosangeles.org/environment/progress/initiatives/vessel-speed-reduction-program/ (accessed on 2 March 2017)

(5) Spaven, L., E. J. Gregr, J. Calambokidis, L. Convey, J. K.B. Ford, R. I. Perry, and C. Short (2006). Draft Recovery Action Plan for Blue, Fin, Sei, and Right Whales (Balaenoptera Musculus, B. Physalus, B. Borealis, and Eubalaena Japonica) in Pacific Canadian Waters.” Nanaimo: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/327242.pdf.

(6) International Whaling Commission (IWC) (2016). Identification and Protection of Special Areas and PSSAs: Information on Recent Outcomes regarding Minimizing Ship Strikes to Cetaceans. International Maritime Organization. 12 Feb. 2016. (Accessed 31 Mar. 2017) https://iwc.int/document_3635.download.

(7) Whale Alert. (2017) Whale Alert: Reducing Lethal Whale Strikes Worldwide. (Accessed on 5 April 2017) http://www.whalealert.org/

(8) Canada’s Oceans Protection Plan: Preserving and Restoring Canada’s Marine Ecosystems (COPP). Prime Minister of Canada. 09 Nov. 2016. (Accessed on 31 Mar. 2017) http://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2016/11/07/canadas-oceans-protection-plan-preserving-and-restoring-canadas-marine-ecosystems.