Thank you all for working with George and I on Thursday and engaging with our discussion questions. It would have been a lot more difficult to do that class if no one was into talking. Anyway, our meta outline for the class was :

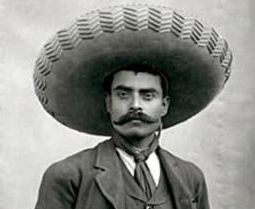

- George would talk about Zapata and Plan de Ayala

- I would talk about what differentiated Zapata’s movement (land)

Two videos –

Zapatistas-

Unistoten-

- In what ways is Zapata’s revolution different from a traditional Marxist revolution?

- Is there room for indigenaity in a Marxist revolution?

- What advantages/disadvantages do movement have that are centered around land.?

- George would connect that movement based in land to the EZLN

As far as the parts that we did get too, I thought it went very well. I really felt the discussion about the paintings that George showed was interesting and I appreciated the discussion around room for indigenaity in Marxist movements. For the next time I will have a better idea of how long the discussion will take and plug my computer in so that it doesn’t die in the middle of the presentation.

Now, for the part that I didn’t get to-

– I planed to finish up by talking about the way the Neo-Zapatista movement has been represented/romanticized and finally think about how we can engage in a positive way with contemporary movements that are in the global south.

Quote from: Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections

In what ways does Romanticization/simplification undermine a movement?

What are the advantages/disadvantages to have an idolized leader/martyr?

How can you engage in a meaningful way with a movement that is in the global south and resist the move to romanicize/simplify?

Quote from a paper by Juanita Sundberg (ubc geography) on North South solidarity –

As posed by United Statesians or Canadians, the question “how can we help” suggests that solidarity is about helping to defend the rights and freedoms of differently situated others. The answer developed by H.I.J.@.S. members suggests that such rights and freedoms are not natural to places like the US or Canada, but are derived from political struggle and therefore can be taken away. In persuading Canadians or United Statesians to become active in struggles for well-being and dignity in their own communities, H.I.J.@.S.-Vancouver are not suggesting that they turn inward and focus on struggles at home rather than abroad. Instead, the idea is that if people in the North try to work from their own experience then they will be in a better position to listen to and collaborate with others involved in equivalent struggles in different locations.

…..Mutuality in solidarity encourages individuals and collectives to speak for themselves, while walking with others to contest neoliberal models that privilege the concerns of multinational corporations over those of civilian populations. We offer these reflections in the hope of inspiring ongoing efforts to re-think solidarity and re-configure resistance through collaboration across borders.

Thanks again to you all and hopefully it goes well this week too!