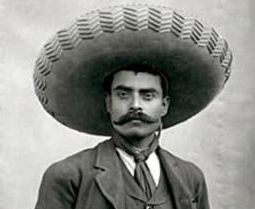

Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! tells us that the fundamental conflict at the heart of the Mexican Revolution concerns land. Indeed, “land and liberty” (tierra y libertad) has been the banner under which has historically erupted, in Mexico as in many other agrarian societies. But this is a conflict also between the countryside and the city, and between different temporalities. The film opens with a delegation of peasants, from the southern state of Morelos, disarming themselves as they enter the national palace in Mexico City to petition President Porfirio Díaz over a land dispute. By giving up their machetes they are also handing over their instruments of labour, but in any case they are already unable to work as the local landowners have used barbed wire to fence off the fields where they have historically harvested their crops. Díaz, paternalistically addressing them as his “children,” tries to fob them off by telling them to be patient, to verify their boundaries and settle things through the courts. “Believe me, these matters take time,” he tells them. All but one of the group is pacified by the president’s vague reassurances. “We make our tortillas our of corn, not patience,” he declares. “What is your name?” asks Díaz, riled up. “Emiliano Zapata,” comes the answer. Díaz circles the name on a piece of paper in front of him, and we have all the clues we need for the rest of the movie: Zapata is different, a man to watch, who will not bow down to authority.

Much later comes a scene in which the roles are reversed. We are in the same office, but Díaz has been overthrown and now it is Zapata who is, temporarily at least, in the position of the president, receiving petitions. In comes another delegation of men from Morelos, seeking to resolve a problem with their land. The complaint is against Zapata’s brother, who has taken over a hacienda whose lands had been redistributed. Now it is Zapata’s turn to prevaricate: “When I have time, I’ll look into it.” Again, however, there’s one man among the petitioning group who won’t put up with such delays: “These men haven’t got time,” he calls out. “The land can’t wait [. . .] and stomachs can’t wait either.” To which now it is Zapata who bellows: “What’s your name?” But on turning to a list similar to Díaz’s, about to circle the offending man’s name, he realizes the situation in which he has found himself, repeating the sins of the past. So Zapata, the true revolutionary, tears up the paper and angrily reclaims his gun and ammunition belt, to head back to Morelos with the men and sort out the problem straightaway.

Revolutions tend to repeat, the film suggests, but something always escapes. Towards the very end of the movie, as we suspect that Zapata is doomed, about to be swallowed up by the very revolution that he helped to start, Zapata’s wife, Josefa, asks him: “After all the fighting and the death, what has really changed?” To which Zapata responds: “They’ve changed. That’s how things really change: slowly, through people. They don’t need me any more.” “They have to be led,” Josefa says. “Yes, but by each other,” her husband replies. “A strong man makes a week people. Strong people don’t need a strong man.” This, however, is the basic tension around which the film revolves: it wants both to glorify (even romanticize) Zapata, and yet also to suggest that it’s the glorification of men like him that leads the revolution to fail. Indeed, Zapata is paradoxically glorified precisely in so far as he consistently refuses adulation. And so ultimately Zapata has to die, shot down in a hail of bullets, so that something of his spirit escapes, here (rather clumsily) portrayed through his white horse which is scene, as the closing credits roll, wild and free on a rocky crag.

Meanwhile, the more basic contradiction that this movie has to negotiate is that it sets out simultaneously to praise and to damn the very idea of revolution. The people’s cause is portrayed and eminently just, and it is clear that the normal political channels of protest or redress are blocked. What’s more, the film lauds Zapata’s instinct for direct action, his taking sides with the temporality of immediacy and against the endless procrastination imposed by bureaucracies of every stripe. (Surely something of this position-taking has to do with the medium itself: Hollywood always prefers men of action to bureaucrats, however much it is run by the latter rather than the former.) But we are not to take the obvious lessons from this portrayal. This movie was, after all, made at the height of the McCarthyite era, indeed in the same year that director Kazan himself would testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee–and, to lasting controversy, would sell out a number of actors and artists who he reported were (like him) former members of the Communist Party. Viva Zapata! had to be, as Kazan himself testified to the Committee, an “anti-Communist Picture.”

So we see how revolutions soon become morality plays, in which what is at stake is less their immediate impact than the lessons that others should or should not draw from them. Interpreting or representing the revolution soon becomes the site of a struggle that threatens to obscure the battles that the revolutionaries themselves fought. And sometimes the most effective counter-revolutionary narratives are the ones that claim to present the revolutionary cause with the most sympathy. Is it any wonder that John McCain, the former Republican candidate for the US Presidency, should tell us that Viva Zapata! is his favourite film? Or perhaps the point is that even the most counter-revolutionary representation has to acknowledge the attraction of armed revolt in the first place.