What are eco-schools?

Eco-schools develop students’ capabilities in six areas, experience, reflection, knowledge, vision for a sustainable future, action taking for sustainability and connectedness (Wilson-Hill, 2010). Students are trained in action competence, that is, their ability to plan for a more sustainable future as well as a meta-cognitive understanding that their learning is a tool of empowerment.

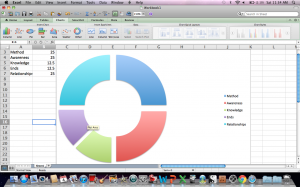

Eco-schools in the MAKER framework

- The MAKER framework is composed of five elements:

- Method: The skills and techniques teachers use to assist students in gaining the knowledge, understanding, and skill that teachers intend their students to achieve.

- Awareness: what the teacher knows about his or her students, including such things as their interests, talents, and concerns; their personal histories and family backgrounds; and their performance in previous years

- Knowledge: Covers what a teacher knows about the subject matter they are teaching

- Ends: The purposes a teacher has for his teaching and for his students

- Relationships: The kind of connection that teachers forge with their students

(Fenstermacher & Soltis, 2009)

These elements inform instructional priorities during all phases of planning, implementation, and assessment.

With its emphasis on understanding sustainability issues and developing student skills to take action on sustainability, the eco-schools are clearly ends driven.

Method is also emphasized in the eco-schools as teachers are expected to take students through a specific type of inquiry process.

Fenstermacher and Soltis’ Approaches to Teaching

Eco-schools fit well with the liberationist approach to teaching. According to Fenstermacher and Soltis, in the liberationist approach the manner in which students learn is as important as what they learn (49, 2009). In terms of eco-schools the focus on students being meta-cognitively aware that learning skills and knowledge must be purpose driven and must be eventually translated into some sort of action in order to be meaningful and relevant is an indicator that educators in these institutions value the means by which students are instructed. In learning about sustainability and inquiry for the purpose of supporting sustainability, students are exposed to a certain manner or principles of procedure appropriate to the study of sustainability.

Eco-schools are a good fit with the emancipatory branch of the liberationist approach. The emancipatory approach emphasizes a strong connection between theory and praxis which is reflected in the eco-schools emphasis on knowledge as a means to imagining and implementing praxis.

According to Fenstermacher and Soltis, in the emancipatory approach, “the students and their teacher must become collaborators, co-investigators developing together their consciousness of reality and their images of a possible, better reality.” (52, 2009). Compare this to enviro-schools’ emphasis on helping students envision and strive for a better future, “It’s about working out how to live so that our society and economy nourishes the natural systems that give us life. Enviro-schools gives young people an opportunity to explore real life challenges and to apply their abundance of energy and ideas.” (Eco-schools, n.d.). According to the enviro-schools’ website, through the inquiry students are encouraged to become teachers and leaders in their communities. This focus on helping students envision a better future and imagine how to take action to make it happen is reflective of an emancipatory orientation.

What about reading and writing?

With its emphasis on students co-constructing problems and solutions at first glance, eco-schools appear to be a free for all of sorts, and some may be concerned that the schools would neglect basic academic skills required for citizenship and future employment.

The enviro-schools, however, do not view a focus on literacy and an inquiry approach as mutually exclusive. Rather, they view the acquisition of literacy skills as an essential component of developing students’ capabilities to go through the action learning cycle.

While an executive might be concerned that learning about the environment will detract from the amount of time that students spend learning how to read and write, an investigation into the literacy learning going on in the schools found that the focus on knowledge with a social purpose enriched literacy learning through authentic learning activities, the development of critical reflective and thinking

Bloom on his head?

The approach, and in particular the success of literacy in this environment, challenges theories such as Bloom’s taxonomy which assumes that skills and knowledge are gained sequentially in a linear fashion going from least complex to most complex. This approach assumes that students go through cycles, and are capable of engaging in activities such as evaluation and synthesis at the same time as they develop the ability to recall information.

This school is a powerful argument for the emancipatory approach. While in the executive approach students learn literacy for literacy’s sake, literacy which serves the greater good of humankind leads to rich literacy opportunities.

References

Enviroschools Foundation. (n.d.) The Enviroschools Programme. Retrieved from http://www.enviroschools.org.nz/Enviroschools-programme-overview

Fenstermacher, G. D. & Soltis, J. F. (2009). Approaches to Teaching, 5th Edition. New York, New York: Teachers College Press.

Wilson-Hill, F. (2010). Better Understanding Educational Outcomes Connected to the New Zealand Curriculum in Enviro-Schools. Hamilton, New Zealand: The Enviroschools Foundation.