What is jurisdiction? It, like “fee simple” and “freedom” and “servitude” (Freedom and Servitude), is a term with no colloquial meaning of significance. It comes from two words, jus and dicere. Jus means law, or right(or soup, as in au jus) and dicere means “to speak.” Jurisdiction, therefore, is the power of speaking law. This is contracted with jus dare, the power to give law. Here is a biblical example of jurisdiction:

And the LORD said unto Moses, Come up to me into the mount, and be there: and I will give thee tables of stone, and a law, and commandments which I have written; that thou mayest teach them.(Exodus 24:12)

So, the Lord will give tablets of stone to Moses, containing a law and commandments that the Lord has written. This is jus dare. Moses will them teach this law and the commandments, which is jus dicere. And there is nothing especially theological about this, it is simply a way to differentiate between the law giver and the law teacher or speaker. The teacher does not create the law, he teaches it. We can also use this story to see that giving of laws is something that is done by Gods, so, if one does not believe in God or Gods, the whole idea of law may be suspect.

Now we know what jurisdiction is, it is the power to declare (or teach) the law. How is it that a Judge (in the Commonwealth, under Her Majesty the Queen) acquires jurisdiction over a person?

The first, and most proper, is by delegation from the Sovereign. To address this point, we need to understand what a Sovereign is.

The law of god, of nature and of nations created kings: which law is not alterable by any creature (Jenk. 79)

Thus, we see that the law of god, of nature and of nations is all one, and it created Kings. Jenkins uses the singular because it is all one, and this law is not alterable by any creature. This shows that the Sovereign is a natural growth, which Aristotle defines in this way:

Of things that exist, some exist by nature, some from other causes.

‘By nature’ the animals and their parts exist, and the plants and the simple bodies (earth, fire, air, water)-for we say that these and the like exist ‘by nature’.All the things mentioned present a feature in which they differ from things which are not constituted by nature. Each of them has within itself a principle of motion and of stationariness (in respect of place, or of growth and decrease, or by way of alteration). On the other hand, a bed and a coat and anything else of that sort, qua receiving these designations i.e. in so far as they are products of art-have no innate impulse to change. But in so far as they happen to be composed of stone or of earth or of a mixture of the two, they do have such an impulse, and just to that extent which seems to indicate that nature is a source or cause of being moved and of being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily, in virtue of itself and not in virtue of a concomitant attribute. (Aristotle, Physics, Book II.i)

Thus, the law of nature created Kings, and this is because Kings exist by nature. The King may get up and say “let us have breakfast,” where a bed, or a chair, or a coat cannot. So the King is a natural body, and the King naturally has jurisdiction. Bracton covers this in two sections,

For what purpose a king is created; of ordinary jurisdiction and Why there are justices and of delegated jurisdiction.

We have spoken in the next [preceding] of ordinary jurisdiction which belongs to the king. Now we must discuss delegated jurisdiction, where one having no authority of his own has authority committed to him by another, [But] since he cannot unaided determine all causes [and] jurisdictions, that his labour may be lessened, the burden being divided among many, he must select from his realm wise and God-fearing men in whom there is the truth of eloquence, who shun avarice which breeds covetousness, and make of them justices, sheriffs, and other ministers and officials, to whom there may be referred doubtful questions and complaints of wrongdoing; men who will not stray either to the left or the right from the straight path of justice for material prosperity or fear of adversity, but who will judge the people of God equitably, so that one may say of them, with the psalmist, that from their countenance came forth the judgment of equity. (Bracton, v. 2 p. 306)

Thus, ordinary jurisdiction belongs to the King, and everyone else who has jurisdiction has it by delegation. This is the greatest and most proper way to obtain jurisdiction. However, there are other ways by which one might submit to the jurisdiction of “justices, sheriffs, and other ministers and officials.”

This defines the “plea in abatement to the jurisdiction” and specifies some conditions upon its use:

The Defendant must plead in propria Persona, for he cannot plead by Attorney without Leave of the Court first had, which Leave acknowledges their Jurisdiction; for the Attorney is an Officer of the Court; and if they put in a Plea by an Officer of the Court, that Plea must be supposed to be put in by Leave of the Court.

The Defendant must make but half Defence; for if he makes the full Defence quando & ubi Curia consideravit &c. he submits to the Jurisdiction of the Court.

Two more pieces of Latin. In propria Persona means in one’s own person. What you do in propria person, you do for yourself. So, you must plead yourself to use a plea in abatement, though, possibly someone who is not an Officer of the Court might assist you, for that specific purpose. If you appoint an attorney, that is supposed to be by Leave of the Court. Similarly, the Judge might ask “do you want to go talk with the Prosecutor outside?” This is called an imparlance and it is a voluntary submission to the Court.

The phrase quando & ubi Curia consideravit is a but more complicated. Literally, it means “when and where the Court considers.” Thus, if you plead not guilty (or defend against an injury, or claim against your land, etc.), that is making a full defense, because the Court will consider that a full plea. For a full description of the term “Defense,” see 1 Co. Inst. 128b.

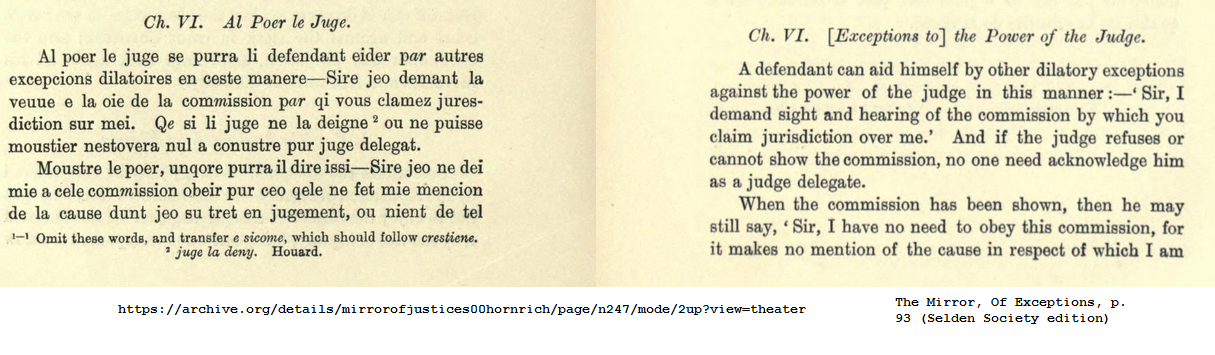

So, how does one make this plea in abatement to the jurisdiction? There are a number of ways, but the most proper is to require sight and hearing of the commission by which the justice claims jurisdiction over you. For one specific form of words, we turn to The Mirror of Justices:

I covered this previously in Exception to Jurisdiction, but it is worth restating here:

A defendant can aid himself by other dilatory exceptions against the power of the judge in this manner:–‘Sir, I demand sight and hearing of the commission by which you claim jurisdiction over me.’ And if the judge refuses or cannot show the commission, no one need acknowledge him as a judge delegate. (7 Selden Society 93)

A second instance comes from the ancient authority Fleta:

Rightful judgments ought to endure and stand firm and be inviolably observed until adequate satisfaction is obtained and so first of all it must be seen whether the justice who has to make judgement is competent. If he is a delegate and has no warrant from the king, what is done before him will be of no consequence as if it were done before one who is not his proper judge, although such as are summoned ought to come. Yet they should not be obeyed, not only when they have no warrant but also even if they show a warrant which has not proceeded from the king. (99 Selden Society 177 (not available for free, as far as I know.))

A third instance comes from Bracton’s De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae:

It is clear that first of all, in order that judgments be valid, it is necessary to see whether the justice has a warrant from the king so that he may judge, for if he has no warrant what will be done before him will have no validity, done, so to speak, before one not his proper judge. The original writ ought first to be read and then the writ constituting him a justice; if he has no such writ at all, or if he has but it is not at hand, he need not be obeyed, unless the original writ makes mention of his judicial authority.(Bracton, v. 4 p. 278)

The form of words is not as important as the spirit, though the form should be stated clearly enough. A Justice must have a “warrant” or “commission” (basically, some document) establishing that they enjoy a delegation of authority from the King. It must name them specifically, and it must state what they are allowed to do. This is a very common sense idea: you need a license to drive a car (albeit by statute) and you need a license to “drive the court” (by the law of nature which created Kings). This applies to all administrative tribunals and every person who claims jurisdiction of any sort over a person.

We have now got several ways in which jurisdiction is acquired over ourself:

- By Commission from the Sovereign

- By appointing an Attorney

- By accepting an Imparlance

- By making full defense

In the next article, we will cover some of the tricks and misconceptions that persist in the legal profession and, I am sad to say, the Judiciary.