The Future of Text-based Communication

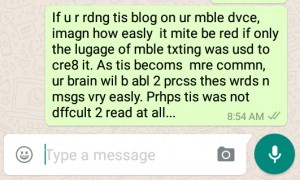

Nye (1997) argues that technology is a social construction. We shape the technology and create it for our needs wants and desires. Yet, the technology also shapes us, and the use of mobile devices is an example that has changed and shaped how we communicate. Historically, SMS messages only allow a limited number of characters per message. When sending longer messages, multiple SMS were sent, each one chargeable. As a cost saving measure, mobile users began abbreviating their words to condense longer messages into a single SMS. This cost-saving measure is less of a concern now with wifi readily available; however the convention of abbreviation still exists. Abbreviating makes typing with thumbs more manageable as well. We also now use emojis to convey emotions or get across a thought using only a picture.

The fact the Oxford Dictionary (2015) deemed an emoji as word of the year suggests a substantial remediation of text is happening; where pictures can replace letters and be called words. The question I would like to explore, is to what extent will mobile technologies continue to change how we communicate?

The fact the Oxford Dictionary (2015) deemed an emoji as word of the year suggests a substantial remediation of text is happening; where pictures can replace letters and be called words. The question I would like to explore, is to what extent will mobile technologies continue to change how we communicate?

Addressing this topic brings up further questions: Will this form of multimedia text become the new norm, even in more formal writing endeavors like research papers and journal articles? We use visuals and media to enhance text, even replace it, but words have traditionally been text-based. Does this mean our dictionaries will need to be updated to include all of the different emojis? Will the common abbreviations we use during texting also show up in the dictionary, and make their way into academic discourse?

Walter Ong, in his book, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, discusses the history of communication technologies, from a strictly oral culture, through the invention of the printing press, which transformed us into the literate society we are today (2002). We are now moving, or perhaps have already moved, into an age of hyper literacy as hypermedia and mobile devices are common communication tools; however, currently, the dominant use of mobile devices is entertainment and email composition. Using a mobile device to compose a significant piece of work, such as a novel or research paper is much less common. This may change. Microsoft and Google have introduced apps for tablets so users can word process and create spreadsheets and presentations using an all-touch interface. As these companies see the popularity and promise of mobile devices, they are facilitating their use through the creation of these apps.

In the same way that e-books have not eradicated the existence of the printed book, perhaps mobile devices will not completely dominate the technology market. It seems that there may still be a place for laptops and computers in everyday personal and professional use. One study, by Hanley (as cited in Ransford, 2014) of university students shows that students use mobile devices more for entertainment than academic pursuits. Laptops are still the preferred choice for academics because of power issues and keyboard accessibility. As tablets become larger, keyboard accessibility may become less of an issue and as memory space within mobile devices also increases the need for a laptop may significantly decline. Although, as the size of screens of mobile devices increases, the mobility of these mobile devices is at risk. A laptop is a mobile technology, as it is not a stationary device; however, laptops are not often thought of in that category. Compared to a phone or tablet, the mass and size of a laptop makes it tougher to carry without a large bag or use without sitting at a table. The new larger tablets being introduced, such as Apple’s iPad Pro, are perhaps in a grey area regarding how mobile they are. It would be difficult to use a tablet of such size in mobile-friendly type setting, such as on the bus or waiting in a doctor’s office.

In the same way that e-books have not eradicated the existence of the printed book, perhaps mobile devices will not completely dominate the technology market. It seems that there may still be a place for laptops and computers in everyday personal and professional use. One study, by Hanley (as cited in Ransford, 2014) of university students shows that students use mobile devices more for entertainment than academic pursuits. Laptops are still the preferred choice for academics because of power issues and keyboard accessibility. As tablets become larger, keyboard accessibility may become less of an issue and as memory space within mobile devices also increases the need for a laptop may significantly decline. Although, as the size of screens of mobile devices increases, the mobility of these mobile devices is at risk. A laptop is a mobile technology, as it is not a stationary device; however, laptops are not often thought of in that category. Compared to a phone or tablet, the mass and size of a laptop makes it tougher to carry without a large bag or use without sitting at a table. The new larger tablets being introduced, such as Apple’s iPad Pro, are perhaps in a grey area regarding how mobile they are. It would be difficult to use a tablet of such size in mobile-friendly type setting, such as on the bus or waiting in a doctor’s office.

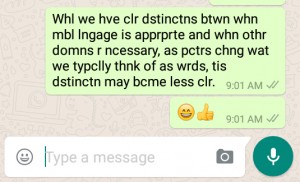

We are able to switch between different modes of communication. Druin and Davis (2009) discovered that using abbreviated language, text speak, is not related to low literacy performance or spelling in other writing domains. They did, however find that there was a perception that text speak hinders an individual’s ability to remember “standard” English. A more recent study suggests that there is a positive correlation between literacy skills and texting proficiency (Kemp and Bushnell, 2011). This suggests that literate individuals are able to readily switch between communication domains; however, as abbreviations commonly used in mobile language become part of our lexicon, it is possible that the lines between these communication domains may become blurred. Abbreviations such as LOL (laugh out loud) and BRB (be right back) are already in the Oxford Dictionary. While they are currently categorized under informal language, there may come a time when they are used in more academic settings. As emojis are now being considered words, our text-based literacy is becoming more and more visual and hypertextual. As informal discourse evolves, why shouldn’t these new informal conventions also work their way into traditionally more formal writing domains?

We are able to switch between different modes of communication. Druin and Davis (2009) discovered that using abbreviated language, text speak, is not related to low literacy performance or spelling in other writing domains. They did, however find that there was a perception that text speak hinders an individual’s ability to remember “standard” English. A more recent study suggests that there is a positive correlation between literacy skills and texting proficiency (Kemp and Bushnell, 2011). This suggests that literate individuals are able to readily switch between communication domains; however, as abbreviations commonly used in mobile language become part of our lexicon, it is possible that the lines between these communication domains may become blurred. Abbreviations such as LOL (laugh out loud) and BRB (be right back) are already in the Oxford Dictionary. While they are currently categorized under informal language, there may come a time when they are used in more academic settings. As emojis are now being considered words, our text-based literacy is becoming more and more visual and hypertextual. As informal discourse evolves, why shouldn’t these new informal conventions also work their way into traditionally more formal writing domains?

The telephone message pad was the first time that shorthand notation was culturally acceptable. Mercer College, in New Jersey, offered courses and published resources to help those, namely secretaries, who needed to learn standardized shorthand (Winning Telephone Tips, 1992). A type of shorthand, albeit a different style of shorthand than used by secretaries, is the notation of choice when using mobile technology. I propose that in the near future, if it is not happening already, schools will begin offering courses in effective mobile communication. I did not find any evidence that it is yet happening, but as mobile communication is becoming a dominant communication mode, this type of learning could become relevant.