Limited Editions Club Letter

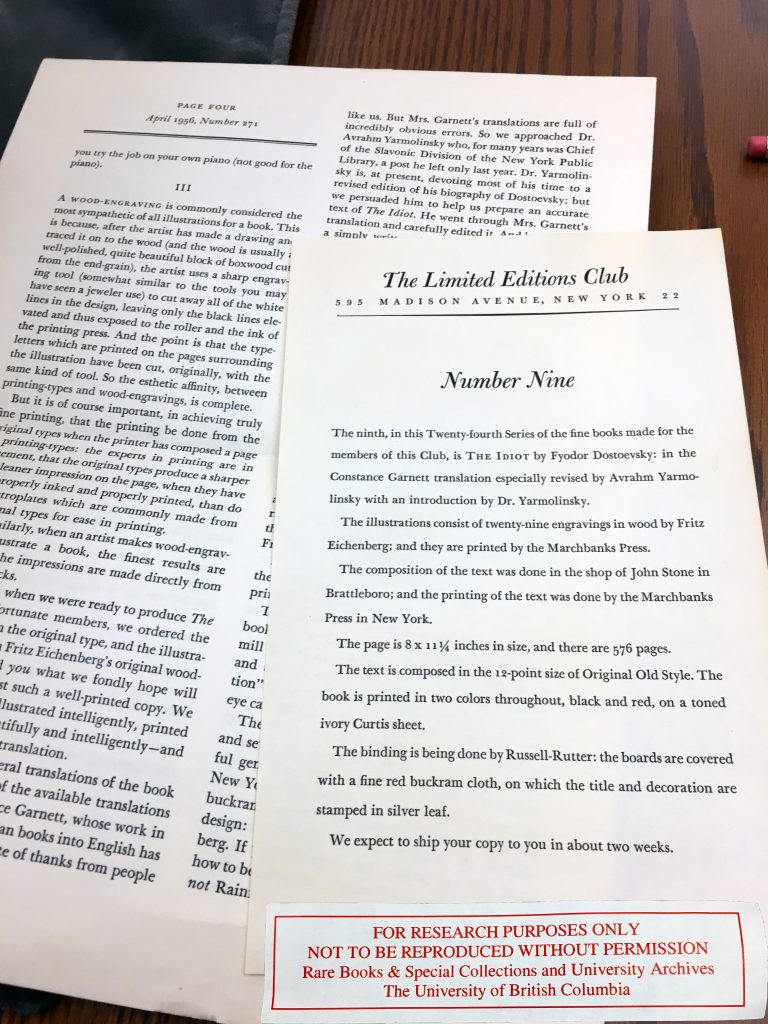

The Rare Books and Special Collection’s edition of the 1956 Limited Editions Club edition of The Idiot includes two loose-leaf pamphlets that were issued as part of the Limited Editions Club’s subscription service. A one-sided sheet gives the subscriber technical information about the book’s production: about its illustrations, text composition, page dimensions and count, and about the book’s material features.

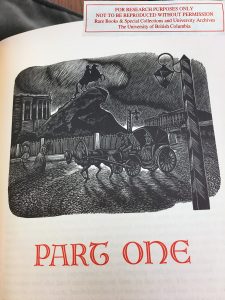

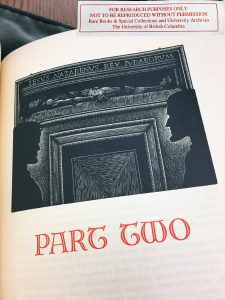

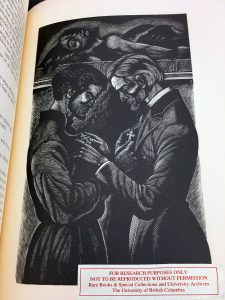

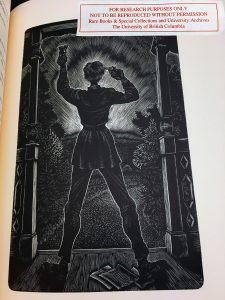

The second pamphlet is a four-page “Monthly letter” from the Limited Editions Club. This one, that came with this edition of The Idiot is entitled, “How to Be a Prince”. The letter gives a brief outline of the history of Russian writers, including the most influential modern Russian novelists–among which is Dostoevsky. The letter goes on to compare Fritz Eichenberg (this edition’s illustrator) to Dostoevsky, claiming that Eichenberg as one of the greatest illustrators of the 20th century. The latter part of the letter describes the value of this edition, justifying the quality of the book’s construction to the subscriber and reader.