Click the link to learn more about whale sharks and their conservation !

If You Own a Wetsuit You Might be Part of the Problem: The Role of Neoprene in Marine Conservation.

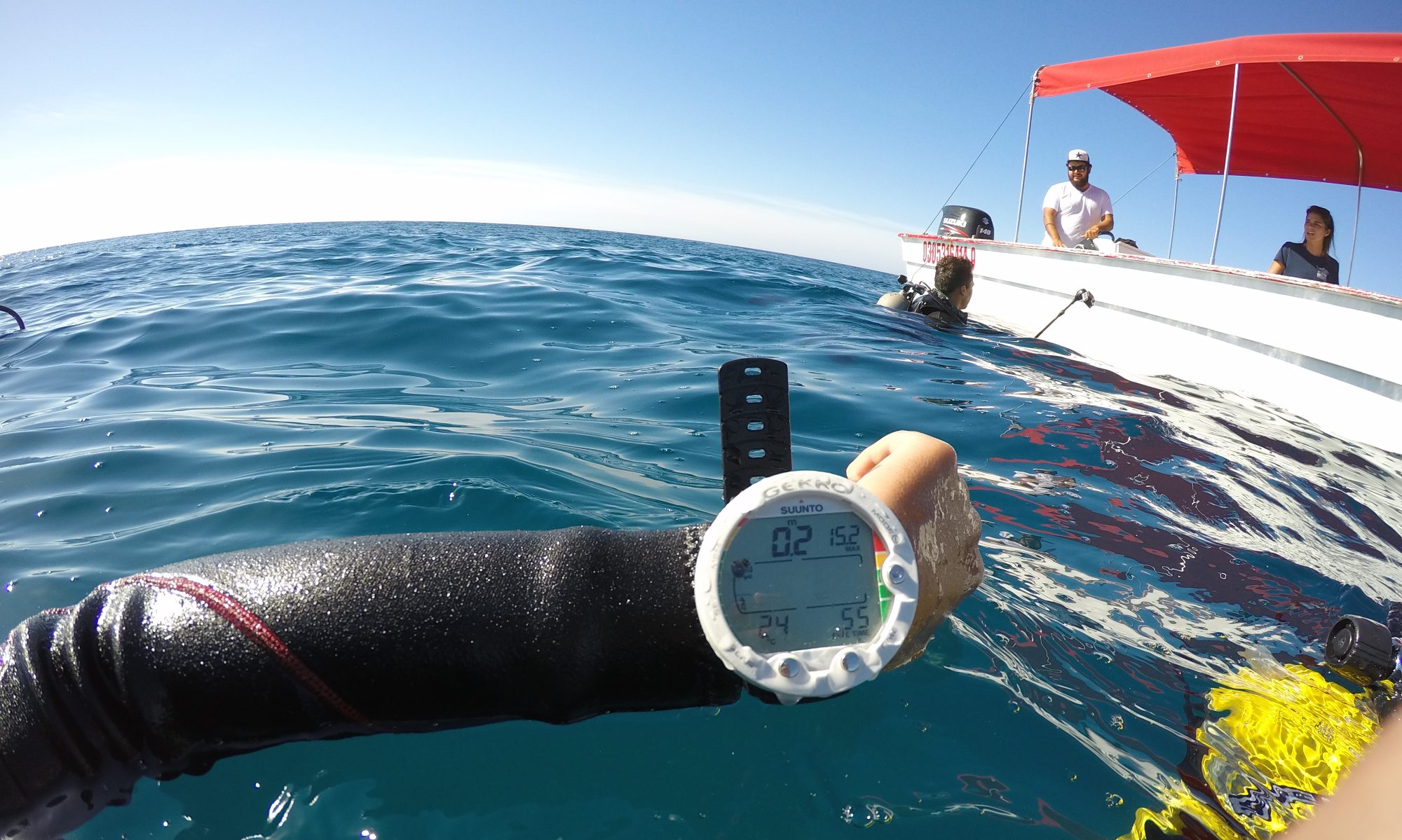

I own a wetsuit.

If you’ve ever been diving, surfing, or doing pretty much any ocean sport that requires a little bit of protection, chances are you’ve worn one as well. It doesn’t matter if you live in warm tropical waters of the Caribbean or the icy waters of the Pacific Northwest—if you live in close proximity to the coast and are remotely interested in spending time in the ocean, you own a wetsuit.

The manufacturing of this second skin however comes at a price for the ocean and the planet. Wetsuits are made from neoprene, which is a petroleum based material with a resource-intensive manufacturing process. Drilling, use of toxic chemicals, and long-distance transportation are often part of the supply chain. Waste is another issue, since wetsuits have a life of about two years and nearly half a million surfers buy a new suit each year, creating about 380 tonnes of neoprene waste (Hook, 2018).

A few companies have identified the intensive supply chain and waste problem and a growing movement towards the less environmentally-damaging manufacture of wetsuits has followed. Patagonia, Abyssey, and Picture Organic are a few examples of how companies are starting to move away from petroleum based neoprene into more ecologically-friendly alternatives. Patagonia has developed ‘’Yulex” material which is 100 percent natural rubber certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, and “could reduce CO2 emissions in production by up to 80%” (Coen, 2019). Picture Organic uses three methods to make their wetsuits more environmentally sustainable, ‘’NaturalPrene” a natural rubber derived from trees, ‘’Aqua-A” solvent free glue, and the use of recycled polyester lining (PictureOrganic, 2018). A theme that resonates with me from this that we often touch on in lectures is that you can’t get it right the first time, and that sustainable alternatives are the result of trial and error .

In addition to the studying the chemical effects neoprene have on marine systems, which requires more research, the social aspect needs to be discussed. While the community of ocean lovers that advocate for the protection of the ocean, do beach cleanups, and have expressed the need for more ecologically-sound sunscreens, they still wear products that are energy intensive and derived from extractive sources, and the shelf life of the product leads to the necessity of purchasing another one when it rips or it’s simply to old.

There should be more pressure on companies to search for alternate materials that have less impact along their production process. It is not to say that owning a wetsuit makes you a bad person, or a hypocritical marine conservationist, but there should be a shift towards research and development of alternative materials that will leave petroleum based production in the past.

Find Pablo on TWITTER

References

https://www.picture-organic-clothing.com/en/wetsuits/

Hook, Amy, April 2018, Wavelength Magazine, https://www.wavelengthmag.com/need-talk-wetsuit-toxic/

Coen, Jon, January 2019, Adventure Sports Network, https://www.adventuresportsnetwork.com/gear/patagonia-overcomes-hurdles-improve-natural-yulex-wetsuits/

Hello world!

Welcome to UBC Blogs. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!