How we design cities needs an anti-racist revolution.

By: Jo Fitzgibbons (UBC, UW Planning), Joanna Gao (UW Planning), Isha Grewal (UW Planning), Emily Tran (UW Planning), and Katie Turriff (UBC MCRP, UW Planning).

People are rising against police violence and racism globally. Abolitionists argue the system is beyond repair and police forces must be dismantled and replaced by unarmed and compassionate community safety groups.

Dramatic restructuring should not stop there.

It’s naive to think leaders authorizing police budgets aren’t also authorizing urban planning decisions. We must abolish city planning as we know it, and rebuild with anti-racism and anti-colonialism at its core.

Streets are the fixed backdrop of recent protests. These streets, neighbourhoods, and cities are often designed to uphold and spatialize white supremacy.

‘Urban renewal’ strategies beautify streets and raise property values, which often displaces marginalized residents. Infrastructure and service budgets prioritize affluent neighbourhoods, leaving poorer neighbourhoods without adequate transit or other services. Not to mention the dislocation of Indigenous Peoples from their territories, which planning continues to support. This is Canadian planning.

Most planners would hate to think their work advances structural violence, but this is what happens when planners refuse to engage in activism and instead portray their work as unbiased, neutral, and scientific. It may be true that we use data and evidence to make decisions and recommendations, but no recommendation about how resources are allocated is neutral.

We are a group of planning students and recent graduates ranging from undergraduate to PhD level. Recent calls for racial justice made us reflect on whether principles of anti-racism were built into our curriculum and practice. We found the opposite: our education is whitewashed, and our profession upholds racist, colonial structures of oppression. Topics such as redlining and environmental racism, for example, receive insufficient attention in planning education, despite their lasting impacts.

Redlining was – or is, if you consider current financial barriers that People of Colour still experience due to this history – a practice that enforced racial segregation of neighbourhoods through the denial of services and mortgages to Black residents. This practice prevented Black people from owning property and building equity. This is one of the reasons the racial wealth gap exists today.

Environmental racism refers to the planned, spatial oppression of People of Colour. Across North America, communities of colour have less access to green space and are instead located nearer to noxious sites, which impacts health, wellbeing, and childhood development. In Canada, the classic example is Africville, an all-Black neighbourhood in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Africville was denied basic urban services until the city ultimately declared it a “slum” and demolished the community in 1970, dislocating Black residents to make room for the McKay Bridge and a dog park.

Planning curricula largely ignores these racist histories. White voices are typically privileged over Black ones – such as the reverence of Jane Jacobs, a white woman mainly active during the Civil Rights Movement – and comparative disregard for Black activists like James Baldwin who fought slum removal, which disproportionately affected Black and Latino communities in New York.

Additionally, there is little recognition that planning practice in Canada is a tool for organizing Indigenous land for productivity and sale. Or, the discussion ends with a simple land acknowledgement, as if planning is doomed to this reality.

The concept of ‘planning’ exists in all cultures, but not all concepts of planning are rooted in white supremacy and colonialism. Why are Canadian planners stuck in our ways? To break this cycle, planning schools must teach these histories, and practitioners must challenge their assumptions about where and when planning began, and who it primarily serves.

We can start this reform by changing curricula to address the full history of planning, from its violent capabilities to its multicultural possibilities.

Planners must be honest about our profession’s dark history. Assigned readings must reflect the diversity of urban experiences rather than just privilege white voices. Schools must do better to attract, recruit, and retain Black and Indigenous scholars, as full-time, tenure-track faculty members, to teach planning classes, and to sit in residence positions. These recommendations echo some of those Jay Pitter recently published in ‘A Call To Courage.’ These calls to action are not limited to classrooms, as practicing planners have a duty to continue their professional education.

For practicing planners and public servants, doing better means changing racist bureaucratic structures – of which we are all participants – from the inside. It means pushing for more public engagement funding so that Black, Indigenous and other People of Colour are paid for the time and energy they spend sharing their expertise, and actually enabling them to be decision-makers for their communities instead of treating them as data points. It means planning directors need to go beyond signing petitions; they must immediately change their hiring practices. It means being a good listener first, and a technical expert second.

If we really hope to build better, fairer, and more sustainable cities, doing this hard work is non-negotiable. It is time for planning’s anti-racist revolution.

As time passed the content and tone of our conversations turned bleak. “Balong, tita ____ passed away today,” “Will, ____ died yesterday.” I found solace in that their names were not prevalent in my memory but great sadness that I lost an opportunity to reconnect with a relative. Facebook’s market penetration in the Philippines is ninety-six percent (Sanchez, 2020). I don’t consider this a testament to the business acumen of the Facebook team but rather a global need for low cost communication with Families divided by seas and continents. Too often families have used social media as a long-term solution for the colonial legacy of family separation within migration policy. Even if these families were to be reconnected in person, how do you catch up on 23 years of missed time? As time continued to pass, the economic impacts of COVID on my Lola became more prevalent. My Grandmother rented out the front of her home in order to help pay for her living expenses and home. Where a front door should have been stood a small motorcycle store in its place. Spare parts for the many tricycle drivers in the city who drive tourists and individuals in a rush. When COVID hit Manila, like many other cities in the world, tourism took a dive and the small tricycle parts store took a hit as well. My family found themselves sending more remittances to my grandmother. When my Nanay told me about my Lola’s situation I was jaded to the absence of financial aids the Philippine government had for seniors and even more jaded to the historical legacy of colonialism in the Philippines. How could a country with such great material wealth be so unable to help those who need it?

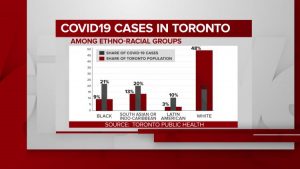

As time passed the content and tone of our conversations turned bleak. “Balong, tita ____ passed away today,” “Will, ____ died yesterday.” I found solace in that their names were not prevalent in my memory but great sadness that I lost an opportunity to reconnect with a relative. Facebook’s market penetration in the Philippines is ninety-six percent (Sanchez, 2020). I don’t consider this a testament to the business acumen of the Facebook team but rather a global need for low cost communication with Families divided by seas and continents. Too often families have used social media as a long-term solution for the colonial legacy of family separation within migration policy. Even if these families were to be reconnected in person, how do you catch up on 23 years of missed time? As time continued to pass, the economic impacts of COVID on my Lola became more prevalent. My Grandmother rented out the front of her home in order to help pay for her living expenses and home. Where a front door should have been stood a small motorcycle store in its place. Spare parts for the many tricycle drivers in the city who drive tourists and individuals in a rush. When COVID hit Manila, like many other cities in the world, tourism took a dive and the small tricycle parts store took a hit as well. My family found themselves sending more remittances to my grandmother. When my Nanay told me about my Lola’s situation I was jaded to the absence of financial aids the Philippine government had for seniors and even more jaded to the historical legacy of colonialism in the Philippines. How could a country with such great material wealth be so unable to help those who need it? in the morning. The emergency room nurse put me in a shared room divided by curtains where many other patients lay waiting to see a doctor. As I sat, fingers numb from what my health implications could mean in the long term, I overheard a conversation a doctor had with a patient. She was a health worker, a hospital cleaner I assume, being tested for COVID due to an alert by the province. After the usual “that felt awful” reaction from a testing swab up the nose, she asked the doctor if it was alright to go back to work. I was immediately horrified in my silence. Without pause the doctor said “yes, that’s alright.” How could someone test and not immediately quarantine? Moreover, how could a health practitioner support that behavior? I immediately wanted to go back home and escape into my bubble. At the time, I didn’t blame the worker for wanting to go back to work, nor do I blame the doctor for potentially causing another outbreak. I blamed the systems and structures that force workers to pay rent during a pandemic. I blamed the policies and programs that make life unaffordable for families of different circumstances. I blamed the historical injustices that place Black, Indigenous, People of Colour at the front lines of COVID-19. I was jaded.

in the morning. The emergency room nurse put me in a shared room divided by curtains where many other patients lay waiting to see a doctor. As I sat, fingers numb from what my health implications could mean in the long term, I overheard a conversation a doctor had with a patient. She was a health worker, a hospital cleaner I assume, being tested for COVID due to an alert by the province. After the usual “that felt awful” reaction from a testing swab up the nose, she asked the doctor if it was alright to go back to work. I was immediately horrified in my silence. Without pause the doctor said “yes, that’s alright.” How could someone test and not immediately quarantine? Moreover, how could a health practitioner support that behavior? I immediately wanted to go back home and escape into my bubble. At the time, I didn’t blame the worker for wanting to go back to work, nor do I blame the doctor for potentially causing another outbreak. I blamed the systems and structures that force workers to pay rent during a pandemic. I blamed the policies and programs that make life unaffordable for families of different circumstances. I blamed the historical injustices that place Black, Indigenous, People of Colour at the front lines of COVID-19. I was jaded. Abolition. When it was first pitched to me, I was numb to the terms. I was jaded. The youths wanted creative control anyway and they had the wealth of knowledge from the elders in our non-profit to lean on and who had been helping them. As a non-profit that dealt primarily with Philippine Indigenous Rights in Southern Philippines, we had a board of directors and elders that we regularly consulted for projects and so I wasn’t worried for the youths. The day before their first recording, I had a briefing with the teens about action items and things they needed for support. The conversation was mechanical as I checked off the list of necessary things in my mind but often drifted to other topics as normally expected for young people working on a big project. At one point the conversation drifted to the necessity of trigger warnings at the beginning of each podcast. I paused. “I don’t think you need to have a trigger warning for your podcast, you don’t go into topics like rape or abuse so I’m not sure its necessary,” I said. The response provoked ideas that I am still reflecting on and the reason why I write this now. “Colonialism is a heavy topic and we should state it in the beginning,” one of the youths responded. What I had thought to be a podcast providing basic information about the nature and realities of colonialism, gender, and race had really been a container to process our collective trauma as Black, Indigenous, People of Colour. These teens recognized not only the necessity of talking about these issues, they demanded that the space start with the mutual understanding that we may not want to talk about issues like colonialism. That speaking to race is like Sisyphus rolling a rock up a hill only to have it roll back down.

Abolition. When it was first pitched to me, I was numb to the terms. I was jaded. The youths wanted creative control anyway and they had the wealth of knowledge from the elders in our non-profit to lean on and who had been helping them. As a non-profit that dealt primarily with Philippine Indigenous Rights in Southern Philippines, we had a board of directors and elders that we regularly consulted for projects and so I wasn’t worried for the youths. The day before their first recording, I had a briefing with the teens about action items and things they needed for support. The conversation was mechanical as I checked off the list of necessary things in my mind but often drifted to other topics as normally expected for young people working on a big project. At one point the conversation drifted to the necessity of trigger warnings at the beginning of each podcast. I paused. “I don’t think you need to have a trigger warning for your podcast, you don’t go into topics like rape or abuse so I’m not sure its necessary,” I said. The response provoked ideas that I am still reflecting on and the reason why I write this now. “Colonialism is a heavy topic and we should state it in the beginning,” one of the youths responded. What I had thought to be a podcast providing basic information about the nature and realities of colonialism, gender, and race had really been a container to process our collective trauma as Black, Indigenous, People of Colour. These teens recognized not only the necessity of talking about these issues, they demanded that the space start with the mutual understanding that we may not want to talk about issues like colonialism. That speaking to race is like Sisyphus rolling a rock up a hill only to have it roll back down.