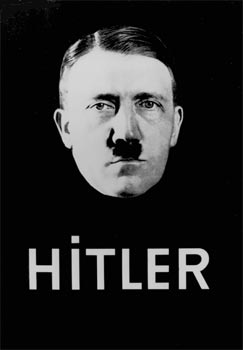

Actual 1932 election poster (source). Actual 1932 voter: “Well, he looks pretty dependable, self-assured, sane. Sure, I’d vote for him. His name is Hitler, right? Okay, yeah, sounds chill.”

Art Spiegelman’s MAUS depicts Jews, Poles, and Germans in distinct forms: as mice, pigs, and cats, respectively — visibly different animal species that reveal a myriad of connotations — and alludes to the propaganda employed through Hitler’s reign during 1930’s Nazi Germany.

Adolf Hitler’s control on the German public grew increasingly stronger as “art, music, theatre, films, books, educational materials, and the press“, authorized by the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment, lead the people towards the Führer’s single vision of nationalism and severe antisemitism. Hitler was a celebrity artist with a dedicated following, on a massive scale.

Leni Riefenstahl‘s beautiful and technical films, infused with masterful imagery that glorified both Germany and its leader, could never disentangle themselves from their association and creation of Nazi propaganda, even after the conclusion of World War II.

Art is forever linked with an artist’s vision and the context in which art exists, and just as Ms. Riefenstahl’s filmography cannot escape Hitler’s Nazi Germany, the dual narratives of MAUS cannot escape the Spiegelmans’ individual subjectivity through their experiences, beliefs, motivations, and values.

And unfortunately, Hitler was a seasoned craftsman with a perverted vision, adept at utilizing propaganda, “the art of persuasion — persuading others that your ‘side of the story’ is correct” (History Learning Site).

Even now as I type, I can think of the many ways in which we are affected by modern propaganda, from this Cenovus commercial (tying together patriotism, capitalism, and scenic cinematography to shed a positive light on the oil sands), this Dove commercial (exposing the insidious nature of the beauty industry while selling the brand to consumers), to Douglas Coupland’s vision of Generation X (a self-absorbed, self-doubting, technology-addicted generation in a fast-paced world).

As a modern society, we must be responsible for discerning the artist’s message, critiquing it from our personal perspective, seeking out other perspectives, and, finally, forming our own opinions of the world we live in.

This post reminded me of a large topic in the art community between whether art should be political or strictly be art for art’s sake. In America, after Vietnam, the postmodern avant-garde movement dictated that art should specifically not be political, as art had been used to further political ideology during the war. You bring up a really interesting notion of should art be political, and if so, how transparent does it have to be about its motives? Or should we just be hyperaware of art’s messages? We also would have to figure out what we are delineating as “political” and “non-political” thought.

Clearly, as you show, art can be harnessed to enact hate crimes and genocide. It would be interesting to try and figure out a way to make sure that we use art responsibly in all spheres of life. Great post!