I still remember when my parents and I immigrated to Canada; I was six years old. On my first day at the new school, I fell asleep during class because I was accustomed to the designated nap-time back in Nanjing. The teacher had to wake me up, then asked if I was okay, and laughed along with my classmates. Needless to say, it was embarrassing and difficult to merely adjust my nap schedule.

There were the multitudinous instances of deviation from the old world I had known and the new world I was thrust into, language barriers aside. My lunches were too strange, too smelly, and too inedible to the other kids, and I was ashamed of the sustenance that my mother or grandmother provided me. Food had never been so difficult to consume until I experienced my own deviance, through other people’s eyes, and this worried me from Grade One until Grade Six. Not only did food mark me as “different”, I was also “wrong”. I thought maybe it was inconsiderate of me to eat rice and fish with the little bones to be picked out by every bite, or it was bad to unveil damp dumplings that smelled of pork and sour vegetables even when eaten cold. I thought that perhaps my sense of taste and smell were skewed or completely opposite from my peers’ in this world.

Fred Wah writes in Diamond Grill how his mother “knows the girls don’t like garlic breath on her boys” (47), echoing my own anxieties, but when confronted by his then-girlfriend’s complaints of his breath, Fred tells her “she’s nuts, I can’t smell a thing and all she has to do is eat some garlic each night for supper and everything’ll be cool” (47). But even Fred can’t handle the “pungent chunks of ginger” (44) in Chinese dishes, and picks them out before eating, much to his father’s chagrin and disappointment that Fred Jr. is not “Chinese” enough.

I also remember when my school-friend’s stepfather scolded me with disgust on his tongue, upon picking her up from my house and meeting me for the first time, for not being “very Chinese” (he is Caucasian, I must note here, but his wife and stepdaughter are both fully Chinese; I could, and still can, see just how narrow his definition of what being “Chinese” or, more specifically, being “a Chinese girl” is — to be submissive, quiet, docile, eager to please), encouraging such stereotypes that are ingrained in North American schema and are altogether troubling, regressive, and, simply, racist.

And even though my appearance may suggest that I have lost touch with my cultural roots, and though I seem to have assimilated into popular North American culture, and though I may not be submissive nor quiet nor docile… my taste in food gives away my thick Canadian disguise, shucks off my acculturated mask, and lets me enjoy the one connection I have to my long-lost culture: my grandmother’s cooking.

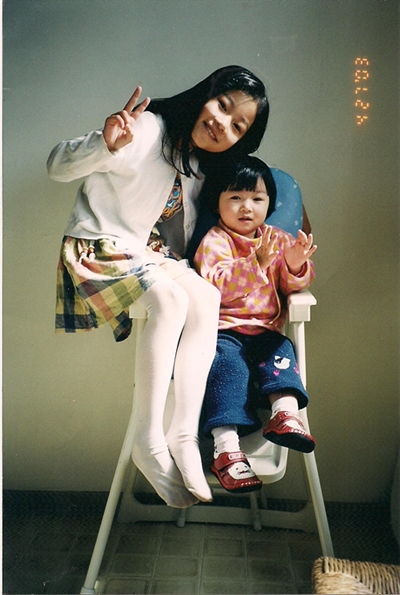

My grandparents speak no more than six words in English, and I speak fragmented Mandarin, so sometimes I am sad thinking that I may never learn the recipes and my heritage will end with my younger sister (born in Vancouver one year after we immigrated here, and still cries about being Chinese on the outside and Canadian on the inside) and me. But sometimes I think I can still learn. Like Fred Wah, when I indulge in the foods that are foreign and/or unpalatable to most of you (dishes without names because I only remember their tastes, smells, and manifestations; dishes that have been around since I was born, since my mother was born, since my grandmother was born), I am indulging in my rich history, my family’s life narrative.