Welcome to our Annotated Bibliography, which we hope will open up dialogue on our research concern: highlighting diasporic authors who are intervening into the discourse of citizenship, resulting in a more global outlook (inspired by Lily Cho’s article “Archives of Diasporic Citizenship” in Canadian Literature, 50th Anniversary Interventions).

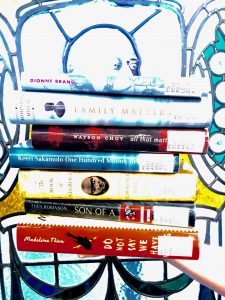

*Photo above of a stack of diverse books blocking the view of a stained glass of King Edward. Brought from King Edward High School to VCC King Edward Campus (now called Broadway Campus). The stained glass will probably be removed soon in an effort to decolonize VCC.

Duff, Christine. “Where Literature Fills the Gaps: The Book of Negroes as a Canadian Work of Rememory.” Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne [Online], 36.2 (2011). Accessed 29 Mar. 2019.

In Christine Duff’s article, she makes the point that a document that listed 3,000 black loyalists and their journey into Canada is one that is lost on the memory of Canadians. Laurence Hill, being a natural storyteller was able to weave a story that would resonate with Canadians and allow them to understand the history. As a storyteller, Laurence Hill’s The Book of Negroes acts as a historical discussion that would not have otherwise been there. Duff argues that the book offers to fill the gaps left open by history and how a piece of literary fiction can be a source of truth. In the article, Duff quotes Toni Morrison, an American novelist who wrote in Site of Memory “facts can exist without human intelligence, but truth cannot”. This further promotes the author’s thesis that literary fiction can be a source of truth and fill the gaps.

The idea that Canada is without innocence is also presented. Canada likes to believe that they should celebrate the end of the Underground Railroad and hide the 200 years of slavery. Canadian history has tried to push the narrative that the nation was far more moral compared to the United States. That notion is false, and the novel sheds light on the more brutal aspect of Canadian history. It also brings up another point of what is truly Canadian. The novel won Canada Reads in 2009 because it highlighted a Canadian author and a Canadian story that was relatively unknown and pushed Canadians understanding beyond comfort.

Works Cited

Boika, Anastasiya. “What makes literature ‘truly Canadian’? A critical look at the annual Canada Reads competition and the pursuit of the great Canadian novel.” Queen’s University Journal, 31 Mar. 2016, queensjournal.ca/story/2016-03-30/arts/what-makes-truly-canadian-literature/.

Brown, Kyle. “Canada’s slavery secret: The whitewashing of 200 years of enslavement.” CBC Radio One, 18 Feb. 2019, cbc.ca/radio/ideas/canada-s-slavery-secret-the-whitewashing-of-200-years-of-enslavement-1.4726313.

Kaadzi Ghansah, Rachel. “The Radical Vision of Toni Morrison.” New York Times Magazine. 8 Apr. 2015, nytimes.com/2015/04/12/magazine/the-radical-vision-of-toni-morrison.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FMorrison%2C%20Toni&action=click&contentCollection=timestopics®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection.

Nurse, Donna. “Why The Book of Negroes matters.” The Globe and Mail, 14 Mar. 2009,

theglobeandmail.com/arts/why-the-book-of-negroes-matters/article1155363/.

Jetalina, Margaret. “Playwright Making Her Own Way In Canadian Theatre.” Canadian Immigrant, 4 Mar. 2013, canadianimmigrant.ca/living/playwright-making-her-own-way-in-canadian-theatre.

This article from Canadian Immigrant spotlights Carmen Aguirre, a prolific Chilean-Canadian actor, author and play-write. Aguirre states that “I’d started going to acting school, but it soon became clear that there would be few roles available to me as a woman of colour on Canadian stages,” says Aguirre. “At that time [the early 1990s], all the stories dealt with white, middle-class characters and most of them were imported from the U.K. or U.S. I realized that if I wanted to act in Canada, I would need to create my own work.” (Jetalina, Playwright making her own way in Canadian Theatre)

The underlying issue of Canadian theatre’s non-inclusiveness for ethnic actors is still a major problem, fraught with casual racism. Aguirre states. “Since starting her career more than 20 years ago, Aguirre has found that the situation for theatre artists of diverse backgrounds in Canada has definitely improved, but there is still a long way to go. “In the big urban centres of Canada, more than half of the populations are non-white. .. is this story reflected in the large commercial and well-funded festivals? Of course not. If things have improved, it’s only because artists of colour have insisted on making their own work.” (Jetalina, Playwright making her own way in Canadian Theatre)

There are a few theatre companies that assist with the funding of new work for ethnic actors. This article goes on to highlight the Almeda Theatre Company. “For example, this April, her play Chile Con Carne is being presented by Alameda Theatre Company, a unique Toronto-based company that produces the work of Canadian Latin American playwrights.” (Jetelina, playwright making her own way in Canadian Theatre)

She has written over twenty plays and two memoirs. Her first memoir Something Fierce, ” …was nominated for British Columbia’s National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction, the international Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction, was a finalist for the 2012 BC Book Prize, was selected by the Globe and Mail, Quill & Quire, and the National Post as one of the best books of 2011, was named Book of the Week by BBCRadio in the United Kingdom, won CBC Canada Reads 2012, and is a number-one national bestseller.” (Aguirre, Talonbooks, profile). Her Second Memoir is called Mexcian Hooker #1 and My Other Roles since the Revolution. ” is on The Globe and Mail’s, The Ottawa Citizen’s, Quill & Quire’s, and 49th Shelf’s most anticipated books of 2016 lists.” (Aguirre, carmenaguirre.ca/books). As a political refugee from Chile during the Pinochet regime, she took up acting training at Vancouver’s well known theatre training program Studio 58 in Langara College. Her First play, written at Studio 58 is called, In a land called, I don’t remember, Published by Talon books in an anthology called Chile Con Carne and Other Early Works. “She explored her dual identities of Chilean and Canadian, through the two lead female characters.” (Aguirre, Carmenaguirre.ca/bio). Her most well known and popular plays are Chile Con Carne, The Trigger, Refugee Hotel, which one the 2002 Jessie Richardson award The Refugee Hotel won “the 2002 Jessie Richardson New Play Centre Award” (Aguirre, Imago theatre bio) and Blue Box.

The takeaway message from this article is succinctly stated in the final paragraph. “For newcomers of any ethnicity who aspire to careers in theatre, Aguirre adds that the only way forward is to create one’s own opportunities. “If you don’t want to write your own plays, then find plays by diverse writers that interest you and produce them yourself,” she says. “Sign up for the Fringe festival, go bang on doors with ideas; don’t sit at home waiting for the phone to ring. If theatre really is your calling, you will find a way to make your dreams a reality.” (Jetalina, A playwright-making-her-own-way-in-canadian-theatre)

Works Cited

Aguirre, Carmen. “Blue Box » Books » Talonbooks”. Talonbooks.com, 2019, talonbooks.com/books/blue-box.

—. “Carmen Aguirre | Bio”. Carmenaguirre.ca, 2019, carmenaguirre.ca/carmen_aguirre_bio.html.

—. “Chile Con Carne And Other Early Works » Books » Talonbooks”. Talonbooks.com, 2019, talonbooks.com/books/chile-con-carne-and-other-early-works.

—. “Her Side Of The Story.” Imago Theatre, 2019, imagotheatre.ca/her-side-of-the-story-carmen-aguirre/. Accessed 28 Mar 2019.

—. “Playwrights | Playwrights Theatre Centre”. Playwrights Theatre Centre, 2019, playwrightstheatre.com/playwrights/.

—. “The Refugee Hotel.” Talonbooks, 2019, talonbooks.com/books/the-refugee-hotel.

—. “The Trigger.” Talonbooks, 2019, talonbooks.com/books/the-trigger.

Dyck, Daryll. “Review: Carmen Aguirre’S Mexican Hooker #1 Is A Powerful Victory For Survivors Of Abuse.” The Globe And Mail, 2019, theglobeandmail.com/arts/books-and-media/book-reviews/review-carmen-aguirres-mexican-hooker-1-is-a-powerful-victory-for-survivors-of-abuse/article29717408/.

Jetalina, Margaret. “Playwright Making Her Own Way In Canadian Theatre.” Canadian Immigrant, 2019, canadianimmigrant.ca/living/playwright-making-her-own-way-in-canadian-theatre.

Zentilli, Francisca. “Something Fierce: Memoirs Of A Revolutionary Daughter, By Carmen Aguirre”. The Globe And Mail, 28 June 2011, theglobeandmail.com/arts/books-and-media/something-fierce-memoirs-of-a-revolutionary-daughter-by-carmen-aguirre/article590992/.

Lee, Jen Sookfong. “Open Letters and Closed Doors: How the Steven Galloway Open Letter Dumpster Fire Forced Me to Acknowledge the Racism and Entitlement at the Heart of CanLit.” Humber Literary Review, n.d, humberliteraryreview.com/jen-sookfong-lee-essay-open-letters-and-closed-doors/.

Jen Sookfong Lee is another Vancouver-born Canadian-Asian author that’s a UBC alumnus. Her novel, The Better Mother was shortlisted for the City of Vancouver Book Award. She’s also a radio personality, speaking on many shows, such as CBC’s On the Coast. She currently teaches at Simon Fraser University.

In this article, she expresses that “CanLit has never been about the diversity of voices or even fairness.” She goes to explain how white editors disregard stories of other cultures and casually throw out harmful comments, which can scar someone far greater than intended. She says the experience that hurt her most is when an editor rejected her saying that it didn’t “build on my existing audience.”

This article not only shows the power of words but also how racism can still unknowingly affect our literary sphere in a big way. Like the last article, it shows that the lack of existence of diverse writing can create a cycle of it never being published, as the editor was concerned that it didn’t fit in with rest of their books. How does it make sense that in Canada, out of all places, that writing of another culture is too strange to publish? We need to take action.

Works Cited

Bryden, Diana Fitzgerald. “The Better Mother, by Jen Sookfong Lee.” The Globe and Mail, 29 June 2011, theglobeandmail.com/arts/books-and-media/the-better-mother-by-jen-sookfong-lee/article599007/.

“’I Invited These Indigenous Writers … and Then I Insulted Them:’ Hal Niedzviecki on Appropriation Uproar.” CBC News, 15 May 2017, cbc.ca/news/entertainment/niedzviecki-interview-video-1.4115815.

Lee, Jen Sookfong. “About.” Jen Sookfong Lee, sookfong.com/?page_id=6.

Marche, Stephen. “CanLit’s Colonial Habit: Literature in the Age of Reconciliation and ‘peak’ diversity.” Literary Review of Canada, 2017 Nov. reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2017/11/canlits-colonial-habit/

This article is written by Stephen Marche, who is a Canadian novelist, essayist, and cultural commentator. I emphasize cultural commentator because this article delves into the debate of cultural appropriation, multiculturalism, and Indigenous Canadian literature and comes to some interesting conclusions. The central concerns of this article involve questioning how the framework of the debate is usually on social media or other new media, avenues which are meant to provoke and incite outrage. He says having this conversation in a civil way is so important and argues that “its political consequences could not be larger for Canada: How are we to approach reconciliation? What is the future of multiculturalism? What does decolonization look like? I will not concede that the cultural questions are less important. They will tell us whether we are a meaningful country.”

Marche’s opinions are that, first, the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action is required reading; we must collectively acknowledge the horror of the how erasing Indigenous people was the way Canada was “built”. But also, we are not even close to reconciliation because we haven’t accepted the truth. As for multiculturalism, he claims Canada is not even as multicultural as we like to believe—that we use that word because it makes us feel good about ourselves. He calls the moment post-diversity, wondering why immigrants even have to write about their culture. The dichotomy March questions is: “if you sell your ethnicity, that is what you are selling. But if you deny your history, how can you be yourself?”

Marche add that we are attempting a radical, political and cultural reconciliation when we truly embrace multi-culture and truth and reconciliation. He also admits that there is no novel “without inhabiting other people bodies and souls” and insists being “cosmopolitan” also involves restraint. He wants us to forget about multiculturalism as a virtue. The main point he emphasizes is that we have to confront Canada’s dirtiness and the shadows, examine all of our “fuck-up-edness.”

Works Cited

Palmer, Tamara J. “Ethnic Literature.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 4 Mar. 2015, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ethnic-literature.

Truth and Reconciliation Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

McNeil, Sarah “Lack Of Ethnic Diversity in Canadian Publishing.” Simon Fraser University. Fall 2017. http://journals.sfu.ca/courses/index.php/pub371/issue/view/1

This article focuses on the lack of diversity of Canadian publishing. The author, Sarah McNeil lays out with two sources that publishing in Canada does not seem to mirror the cultural diversity in the country. She argues that there is still systemic racism in the publishing industry and it cannot be excused. McNeil makes a point that publishers in media came together and put money toward an Appropriation Prize for a white writer to come up with something outside their own culture. She mentions that higher-ups from many popular media companies contributed to this. There seems to be a sense that publishers and media companies are only interested in ways to make money and further their ratings. The belief that readers will only pay attention to white writers is an underlying issue. Although it is clear that there tends to be “token ethnic writer” that is included in literary awards. The writer is only nominated as a gesture to that community or for political reasons. McNeil points to a deeper issue, ethnic writers do not have the same support system of editors that understand their work. The support system also does not include critics that have a full depth of understanding as well publishers who can promote with an understanding. For more writers to get published in Canada it must start from the top. The publishers need to be more diverse as well as the editors and critics. Until there is a support system in place there will not be growth for diverse writers.

Works Cited

Qureshi, Bilal “Yes, we need more diverse books. ‘The Good Immigrant’ answers that call.” Washington Post. 6 Mar 2019, chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/books/ct-books-good-immigrant-20190306-story.html

Wyatt, Daisy “Oscar 2015: Academy criticised after no black or Asian actors nominated” The Independent. 15 Jan. 2019, independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/oscars/oscar-nominations-2015-academy-criticised-for-all-white-nominees-in-acting-categories-9980457.html

Meerzon, Yana. “Theatre And Immigration: From The Multicultural Act To The Sites Of Imagined Communites”. Journals.Lib.Unb.Ca, 2019, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/24302/28111.

Meerzon argues that with the relaxing of immigration policy from the Liberal government of Canada in the mid 1990s, Canada has “Canada became one of the most desirable countries for migration.” (Meerzon, Theatre and Immigration: From the Multiculturalism Act to the Sites of Imagined Communities) as a result “the most significant change in Canada’s population in the late twentieth century: “increasingly diverse” and immigrant artists’ performances “no longer need to appeal either to the traditional white middle-class audience of Canada’s so-called ‘main stages’ [. . .] nor to communities narrowly defined by culture or interest” (Meerzon, Theatre and Immigration: From the Multiculturalism Act to the Sites of Imagined Communities)” The changing of immigration policies directly affect the type of theatre that is produced in Canada.

We would argue that this is semi-true. Although there is an increased number of immigrant theatre professionals, to state that they “no longer need to appeal to … white middle-class audience of Canada’s so-called ‘main stages'” is misleading. It is true that the content of new professional work deviates from a strictly Caucasian source material, Any play-write or theatre professional who wants their work to become nationally produced relies on physical ‘main stages’ throughout Canada, who generally produce established Canadian, English and American theatre. The Shaw Festival and the Stratford Festival are two of North America’s largest theatre companies and produce mainly English works. Tarragon Theatre, The Belfry, The Arts Club, Theatre Calgary, Theatre Passe Muraille, The Citadel theatre and many others use predominantly established Canadian works an attempt to draw audiences in, although, The Belfry in recent years continues to showcase new and diverse Canadian works from a variety of indigenous and ethnic play-writes.

The Canada Council of the arts provides playwriting grants to play-writes who are able to produce theatre with a specific focus to Canadian content, which can help work more to more easily become produced.

Marrzon also suggests that Canadian Theatre is an “imagined community” often creating works, that are not reflective of the real Canadian National identity, “by commenting upon the traumatic events that shaped their personal immigrant experience, these artists create fictional “else-where” and “back-home” environments on stage. Presented to diverse Canadian audiences, these self-reflexive, accented, ironic, meta-theatrical, and estranged environments have become the temporary instances of shared imagined (immigrant) communities; they reflect immigrants’ struggles in second language acquisition, and recognize, challenge, and negotiate the artistic, ideological, and performative tendencies that make Canadian/Quebecois theatre Canadian/Quebecois.7 For many immigrant artists, making a theatrical performance itself becomes a process of creating these imagined communities, a new homeland, which “transcends cultural specificity and encourages the development of an identity that is formed from living in the theatre rather than a society” (Meerzon, Theatre and Immigration: From the Multiculturalism Act to the Sites of Imagined Communities)”

We would argue that although these “else-where” and “back-home” environments, shaped by immigrants is reflective of a part of Canada’s true national identity, one shaped by multiculturalism and shared immigrant experience.

Due to the search for Canadian identity, we have seen many theatrical and television professionals rise through the ranks of popularity in recent years. Marrzon argues that the rise in the immigrant population has allowed for a new genre of Canadian theatre. “This special issue takes this statement further and focuses on the cultural, personal, and artistic output of immigrant theatre artists who have been working in Canadian theatre for several decades The representation of an immigrant/immigration on stage constitutes a self-referential move in Canadian theatre.”(Meerzon, Theatre and Immigration: From the Multiculturalism Act to the Sites of Imagined Communities)” We see examples of this in many popular theatre works and tv shows. For exam, The CBC comedy “Kim’s convenience” started off as a Fringe festival play that made it’s way across the country to become nationally produced. The script was eventually adapted into the CBC comedy show “Kims Convenience” currently airing. Another example is the prolific author, actor and play-write Carmen Aguirre, a Chilean-Canadian whose works delve into the duality of identity between Canadian and Chilean heritage.

Works Cited

Aguirre, Carmen. “Bio.” carmenaguirre.ca, 2019, carmenaguirre.ca/carmen_aguirre_bio.html.

Choi, Ins and Kevin White, creators. “Kim’s Convenience.” Thunderbird Productions, 2016.

“Explore And Create.” Canada Council For The Arts, 2019, canadacouncil.ca/funding/grants/explore-and-create.

Meerzon, Yana. “Theatre And Immigration: From The Multicultural Act To The Sites Of Imagined Communites”. Journals.Lib.Unb.Ca, 2019, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/24302/28111.

Thien, Madeleine. ACWW: Madeleine Thien at literASIAN. 24 Nov. 2013. youtube.com/watch?v=uvIX2cEGgZ0

Madeleine Thien is a Vancouver-born Canadian-Asian author who graduated at UBC with an MFA in creative writing in 2001. She writes stories that are deeply cultural and her third novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, has won the Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction.

In this video, she discusses the difficulty that female writers of colour face in Canada’s literary environment. When it comes to their works not being recognized, she blames the critics, who are mostly white men, that they “simply do not have a great depth of knowledge, whether that be historical context or literary precedents.”

This video not only articulates many problems that minorities face in publishing but also points at some of its roots. I particularly like how Thien points out the lack of literary precedents possessed by the critics, meaning that they just haven’t read enough of other culture’s stories to appreciate it. It’s a terrible cycle, since these critics can’t appreciate the stories, less gets published, meaning there aren’t opportunities for our future critics to learn.

Works Cited

“Do Not Say We Have Nothing.” CBC Books, 16 Feb. 2017, cbc.ca/books/do-not-say-we-have-nothing-1.3985967.

Elliott, Alicia. “Indigenous Writer Calls out CanLit for Lack of Diversity.” CBC Radio, 18 Mar. 2018, cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/how-indigenous-authors-are-claiming-space-in-the-canlit-scene-1.4573996/indigenous-writer-calls-out-canlit-for-lack-of-diversity-1.4575969.

Lapointe, Michael. “What’s Happened to CanLit?” Literary Review of Canada, May 2013, reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2013/05/whats-happened-to-canlit/.

Lorre-Johnston, Christine. “Madeleine Thien.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 9 Nov. 2016, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/madeleine-thien.

“Why Literary Critics Failed to Understand and Define Austin Clarke, a Canadian Writer Far Ahead of His Time.” National Post, 26 Aug. 2016, nationalpost.com/entertainment/books/why-literary-critics-failed-to-understand-and-define-austin-clarke-a-canadian-writer-far-ahead-of-his-time.

Ty, Eleanor. “Representing ‘Other’ Diasporas in Recent Global Canadian Fiction.” College Literature, vol. 38, no. 4, 2011, pp. 98–114. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41302890.

The author of this article is Eleanor Ty, a professor of English and Film Studies at Wilfred Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, specializing in subjects such as Asian American, Asian Canadian, Canadian literature, graphic novels, lifewriting, and 18th and 19th-century novels.

This article is concerned with the reimagining the representation of “other diasporas”—Ty does not focus on the immigrant writer detailing an experience of Canada in a memoir, instead, she contends that the literature created by writers who go beyond their own histories is an important addition to the understanding our current global community. Ty mentions how, over the decades, different cultural groups have experienced changes in focus: from the politics of recognition of the seventies to the identity politics of the eighties, landing in the present where globalization and technology are affecting literature. She believes that Canadians of other cultural identities are now able to write about diasporic communities in which they do not belong. Lily Cho, whose is quoted in this article, “Diaspora brings together communities which are not quite nation, not quite race, not quite religion, not quite homesickness, yet they still have something to do with nation, race, religion, longings for home which do not exist” (Cho qtd. In Ly 100).

Ty investigates three novels: Dionne Brand’s What We All Long For, Camilla Gibb’s Sweetness in the Belly, and Michael Ondaatje’s In the Skin of a Lion in order to highlight dislocated writers who have crafted novels about places/times they do not belong. In Brand’s case, she is a Trinidad-born writer whose novel is about the struggles of Vietnam refugees in Toronto; Gibb is not an ethnic minority but is an anthropologist who was born in Britain and who has lived in Ethiopia, her novel is about a European Muslim woman in Ethiopia; and Ondaatje is of Dutch-Tamil family born in Sri Lanka whose novel is about Macedonian, Italian, and Bulgarian immigrants in Toronto in the early twentieth century. The novels Ty explores are cross-cultural and highlight other places, other times, and are written by authors of diverse backgrounds. She suggests such novels “deterritorialize” diasporic identities, expanding the narrow view of Canadian Literature.

Ty mentions the word cosmopolitan many times and seems to use it in a way that conjures the global, travelling, not-quite-Canadian-but-not-quite-anything else citizen. The article could have been helped by the inclusion of an Indigenous novel to fully flesh out the deterritorializing aspect of what she was trying to achieve, although there are more efforts now to promote and study Indigenous literature, so may be used more in the future as a source of scholarly articles. I believe the usefulness of this source in the context of our intervention lies in the way the article goes beyond multiculturalism in Canada and extends towards a Canadian global view of literature.

Works Cited

Indigenous Literary Studies, 2019. indigenousliterarystudies.org/home

Pivato, Joseph. “Atwood’s Survival: A Critique.” Athabasca University, 26 Apr. 2016, canadian-writers.athabascau.ca/english/writers/matwood/survival.php

Team “Decolonizing Ourselves”

We are focusing our project on the connection between geography and literature, and, in connection to your topic on culture, geography and culture are very closely linked (the following TEDx gives a bit of insight into the connection between landscapes and culture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5onjyWsWa78).

You speak in your project introduction about how readers need to be inspired to explore the wide range of cultures that have been established within Canada. How do you think that the disconnect between the various cultures established in Canada and their originating geographic places would impact the diversity in Canadian publishing?

Hi Cassie,

I watched the TED talk and was most interested in the part where she talked about looking at “ethnic signatures” of a place. Made me think of how the diaspora in Canada shaped the landscape, from remaining hints of the past such as Indigenous groups’ midden grounds like Marpole Midden in South Vancouver to echoes of Japanese-Canadian internment camps in cities in the Kootenays like Kaslo. I like the image of the landscape in historical/cultural layers, with past and present and everything in between, leaving us to contend with where we ended up today—how is “the landscape our autobiography?” as she says in the video. But to answer your question, I think the disconnect between various cultures in Canada and their originating geographic places impact the diversity in Canadian publishing in interesting ways… we all have to seek out and attempt to find connections and common ground that we might not at first understand—and write about it! In a sense, we are all adding layers to the landscape that will become Canada’s autobiography.

Hi friends!

Our team Maple Syrup Igloos is also interested in looking at the lack of authentic representation of minorities in literature and other mediums, and thus we were intrigued to read through your entries.

I personally was very interested about your entries about theatre and the creation of a new genre where representation can exist, as I had also chosen to explore the idea of minorities in theatre.

This section of your bibliography, “For newcomers of any ethnicity who aspire to careers in theatre, Aguirre adds that the only way forward is to create one’s own opportunities. If you don’t want to write your own plays, then find plays by diverse writers that interest you and produce them yourself” is especially powerful, and I like the reference to Kim’s Convenience – Go Canada! In our bibliography, we explored another example in which the Indigenous minority decided to revamp traditional European narratives such as Shakespeare’s work in order to better fit their own narrative – the link can be found here if you’re interested! https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1n2tv7r.11?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

I also agree that it is difficult to secure jobs in the pre-established theatre industry as a minority, and that the creation of this newer sphere in which this kind of representation can exist is a beautiful thing. I’m curious, however, about of the notion of the “imagined communities.” In what way, in your opinion, can immigrant playwrights take the elements of their stories and embody them into their work that make them realistic enough to be an accurate representation of the Canadian narrative?

Another thought – sorry I’m just so excited!

One of your entries also addressed the idea of diaspora and the literature surrounding it, and that nowadays authors can write on diaspora communities that they do not belong to, which subsequently “deterritorializes” diasporic identity and instead widens the currently narrow Canadian literary canon. A quick Google search defined deterritorialization as being “movement by which one leaves a territory,” which it also “constitutes and extends” the territory. I love the duality and existence in two spheres that such a definition brings! In your opinion, when is it okay for people that do not belong to a certain diasporic community to write on said community? Are there boundaries that must be considered?

Hi Katrina,

That particular resource was chosen because it did challenge the notion of what has been a hot topic in Canadian literature (the infamous article by Hal Niezviecki’s “I don’t believe in cultural appropriation”)—it enraged a lot of people because it seemed insensitive and dismissive. But I have had trouble reconciling what he was positing with Ty’s article—isn’t she indeed saying, you can write outside of your culture as if you hold the same knowledge and values? In the end, I don’t think so. I do think that boundaries must be considered, and I believe the deterritorialization may refer to leaving the land, not the culture. Maybe it’s more about raising up immigrant literature, and those whose territory extends outside of Canada who can truly relate a diasporic experience.

Hey Katrina,

Just to add to Andrea’s reply, we believe that when it comes to writing on another culture it comes down to honesty.

We don’t want to misrepresent the communities we talk about, and that requires us to interact with such other communities and learn, which can only be a good thing. Writers must make sure not to write through rose-tinted glasses either, as it can turn it into cultural fetishization, but again, this is a form of dishonesty. Finally, we do think it is important to encourage writers to explore other cultures since a Canadian narrative without representation of minorities, in itself, can be dishonest.

Team “Decolonizing Ourselves”

Hi again,

I also found another interesting article that connects to my other comment that has to do with cultural geography that you may find interesting (https://www.thoughtco.com/overview-of-cultural-geography-1434495).

The end of the annotated bibliography entry for Jen Sookfong Lee also caught my eye. I found your conclusion interesting, especially the statement regarding how literature based around other cultures is considered too “strange” to be published in Canada. This really brought me to question what exactly constitutes Canadian culture. Canada is made up of so many different people from so many different countries (which is very well illustrated by Stats Canada’s website on census data: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Canada&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Ethnic%20origin&TABID=1) and has consequently become a country filled with different cultures, which has only been made easier by globalization. If all these different cultures have landed in Canada and have put roots down in Canada, then why are they not considered part of the Canadian narrative and “Canadian culture”? Are there specific ways we can begin to incorporate literature from other cultures into our current literature that publishers may not believe fits into their definition of Canadian literature? May that require a shift in the popular definition of “Canadian literature?”

Thanks for your thoughts!

Hey Cassie,

Yes! You nailed it right on the head! How in the world is it that a story about a Chinese-Canadian too strange for Canadian audiences? This is the problem that many of these minority authors face in Canada, and as Lee and Thien talk about, the problem lies in with the publishers and critics, who are still mostly caucasian and male. The problem of minority representation in media goes way deeper than just the artists, it starts right at the root of publishing itself: the gatekeepers.

I believe our first goal is to change public perception about multicultural stories, to get people to read it more and enjoy it, but that can’t be done unless we have minority voices also represented at the publisher level. We need our minority authors to start talking and constructively critiquing each other to create an environment we don’t need to rely on the current majority anymore. Finally, as readers, we should support the works of these authors by not only reading their stories but also sharing them with others. Every one of our multitude of cultures that live here makes up the Canadian narrative and we must let the publishers know that this is what the public wants.

Hi Tony,

I think you’ve highlighted a super important issue: gatekeepers! As I’ve written about before (https://blogs.ubc.ca/canadianstorytelling/2019/01/20/32/), new media is one way that minority authors can bypass traditional gatekeepers.

While it’s definitely not an ideal solution, I think that it can be a start, and in a lot of ways has already been a start. New media has allowed previously marginalized communities platforms to express their stories. This, in turn, can lead to more people interacting with viewpoints outside of their own culture. Sites such as Medium (https://medium.com/) allow anyone to publish personal essays, cultural commentary (including commenting on their own culture), and short stories that were previously only published in newspapers and magazines.

It’s my hope that a new generation of gatekeepers is currently interacting with, thinking about, and learning from the literature that isn’t their own, and that these interactions foster a more open-minded approach to Canadian literature in the future.

As I said, this isn’t a complete or ideal solution, but I think that’s one piece of the puzzle as we all work to make Canadian literature more inclusive and representative of Canadian reality.

This is the first time I’ve heard the concept “diaspora” but it is very interesting in regards to Indigenous peoples. According to Google, diaspora refers to immigration and “the dispersion of any people from their original homeland.” Obviously, Indigenous peoples are native to the land that we call Canada.

However, Lily Cho expresses, “The contradictions of diasporic citizenship—the need to be at once insistent on diasporic difference and compliant with the generalizing demands of being a citizen—unfold in the diasporic Canadian literature’s insistence on recovering what Allen Sekula calls the body in the archive” (142).

Canada does not own Indigenous people. It is very important that we do not call Indigenous peoples “Canada’s Indigenous peoples” with the possessive pronoun. This is because Indigenous peoples have been here since time immemorial, and Canada is a geopolitical boundary which settler-colonizers have imposed on the land. But in finding common ground, there is indeed this contradiction of diasporic citizenship. The insistence of difference which acknowledges how we must not assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society and thereby destroy culture/traditions/forms of government as Canadians historically have. We must acknowledge and respect the unique identity of different Indigenous tribes –because they are not homogenous, without “other”-ing Indigenous peoples because ‘Us versus Them’ narratives are harmful. But at the same time, there is the generalizing demands of the importance that the Canadian government has a duty to and must protect the rights of Indigenous peoples.

This is how I interpreted your source material (Lily Cho’s article) in regards to Native politics in Canada, specifically. But I am still very tentatively exploring and learning, I was wondering if I was on the right track?

Works Cited:

Cho, Lily. “Diasporic Citizenship: Contradictions and Possibilities for Canadian Literature.” TransCanada. Eds. Smaro Kamboureli and Roy Miki. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2007. 93-109. Print.

Hello Alexis,

This interpretation of diaspora is not how I understood the article in conjunction with our research group’s strategy. The team we have assembled are aware that exists many authors and artists that are from the diaspora in the global context. There are people from Ireland, France, Nigeria, China, India, Japan and they all contribute to a wealth of literary works that create the framework of intervening with the discourse of citizenship. Canada is lucky to be home to authors and poets such as Fred Wah, a Chinese Canadian poet and Laurence Hill and African-Canadian author who have not assimilated their work but rather challenge the citizenship demands as an immigrant or child of an immigrant.

It is interesting that you used Indigenous perspectives in your interpretation but I believe Lily Cho is commenting on the “immigrant as a diasporatic citizen” and their role in literature. I could have misunderstood though.

The article “Playwright Making her own way in Canadian Theatre” by Margaret Jetalina embodies a large issue in Canadian literary canon and canon-building: there has historically been no space for people-of-colour in Canadian canon. A Chilean-Canadian actor, Carmen Aguirre says that in the 1990s, “all the stories dealt with white, middle-class characters and most of them were imported from the U.K. or U.S”. We see this in Canadian literary canon like “Anne of Green Gables” by Montgomery and “Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town” by Leacock. These can-lit novels both sell a romantic-nationalist picture of Canada –“Anne of Green Gables” sold the image so well the book boosted immigration for Prince Edward Island! Both these books paint a picture of Canada full of beautiful landscapes, ideal prairie/Maritimes ideological spaces, small town camaraderie, beautiful theatres and rich culture, and a disturbing lack of ethnic minority characters. The Canadian prairies and Maritimes have become a sort of ideological space –which erases minority existence from the canon-building, national-romantic dream. In the 1990s, people-of-colour were not being represented in the Canadian literary canon, or the Canadian nation-building canon. There was an image of a white Canada. And this image was so powerful, that as Aguirre says, directors would rather import white actors from the U.K or U.S than write a script which requires an ethnic Canadian actor. Aquirre goes on to say, “I realized that if I wanted to act in Canada, I would need to create my own work”. This is very powerful, because when the literary canon erases your people from history, from existence, from your home, what else can you do? But most powerfully write yourself into the Canadian literary canon.

I very much enjoyed this annotated bibliography, and the hyperlink to “More than a hashtag: Making diverse, inclusive theatre the norm”.

In follow-up, I recommend another source entitled “Prince Hamlet PuSh(es) Shakespeare’s tragedy into fresh territory by Mark Robins: https://www.vancouverpresents.com/arts/prince-hamlet-pushes-shakespeares-tragedy-into-fresh-territory/

This source further reviews the Shakespearean play from your hyperlink. The article emphasizes how having actors from different backgrounds play iconic and well-known characters brings entirely new understanding to the text –a concept which I believe goes hand-in-hand with Voyageur’s goal to highlight diasporic authors to consequent a more global outlook.

Here is an excerpt from the article:

“To have Christine Horne, who plays Hamlet, speak “To be or not to be,” or “Oh, what a piece of work is man,” just resonates differently,” explains Jain. “Or, to have Dawn [Birley], who plays Horatio, sign the speech where Ophelia drowns; just the way she’s able to do it, the visual aspect of it, helps to understand the text in a completely different way.”

Hey Alexis.

Thank you for your well thought out and well written commentary. What a great article on Prince Hamlet! I always think it is super cool when we can revitalize a work, especially Shakespeare, to fit our current time. The fact that they are making the piece bilingual (English and Asl) shows promise of inclusivity. It is becoming increasingly popular for directors to engage in colour and gender blind casting. In 2010, there was a film production of The Tempest which cast Helen Mirren, as Prospero, traditionally a man’s part.

Theatre productions are certainly heading toward inclusivity, but the problem remains that the majority of well known Canadian productions being written cater to mostly white actors. I think adapting old theatre to become more inclusive isn’t a bad thing, but I do believe more new original work needs to be written that reflects Canadian stories that are inclusive.

I believe part of the reason for this is that white play-writes are uncomfortable writing outside their race. They don’t want to offend anyone with ignorance, and in doing so simply just propagate the problem un-knowingly. It’s a problem, I don’t necessarily have a solution for, other than to encourage play-writes to do research, and petition the Canada Counsel of the Arts, for new funding for play-writes of colour.

It is frustrating when the National Arts Counsel won’t even fund established indigenous theatre programs.

Thank you for all the intriguing articles! I especially enjoyed the short video of Madeleine Thien’s speech, where she made some comments that stood out to me:

“How [do we] support artists without limiting them?”

“How [do we] engage their identity without defining that identity?”

“How [do we] speak on behalf of a group, to a group, and as a group?”

These are significant concerns when it comes to minority writers, particularly for Indigenous writers, who have their writing limited to a certain theme of “self-reflective, ironic, meta, and estranged environments”, as mentioned in your first annotated article by Meerzon. Thinking about writing in the context of what Thien said, it can be quite a controversial subject. Literature itself is a medium that should allow the exploration of issues that maybe avoided on everyday platforms, or concerns that were overlooked by society. Theoretically, writers have the freedom of creation and the power of enabling difficult conversations through their work. From the shadows, those with silenced voices should hope to address the subject matter of their passion through storytelling.

Ironically, however, many are horribly limited by the literary community itself. Another comment that Thien made in the video was “Writers react, critique and reward one another […] and decide the works that will be visible, and works that will remain invisible.” Due to the large number of Western critics and their lack of appreciation and knowledge for culturally diverse writing, the freedom that is supposedly granted to writers is taken away. Instead, writers are once again engaged in a struggle for getting their voices to be heard, and are trapped within these “imagined communities” (Meerzon) that only allow the false appearance of artistic freedom.

However, this paradox does not come without reason. Although Canada presents itself as a multicultural nation, I wonder if true multiculturalism is every possible. To be able to embrace every diverse tradition, religion, and belief would mean that there is no collective identity. Literature feeds into the national narrative, and therefore also need to be carefully selected in order for the “Canadian story” to work where it’s convenient. Sure, the nation has begun to allow Indigenous voices into the literary and artistic field. We pride ourselves with the fact that we are seeking education and reconciliation through Indigenous representation. However, how much of their real voices have we heard, and how much of their culture have we really come to understand, if at all? According Thien, we pick and choose the stories that will come into the light or remain in the dark, so are we really listening, or are we simply speaking for Indigenous peoples in a way that fits into our national identity? Furthermore, is there a way that we can achieve true multiculturalism without falling into chaos, or must there be sacrifices made in order to keep the unity of a nation? I am curious about your thoughts on this, thank you!

-Anna

Another one of your annotated articles that I particularly enjoyed was Yana Meerzon’s Theatre And Immigration: From The Multicultural Act To The Sites Of Imagined Communities. If I didn’t misunderstand it, one of the underlying arguments that the artistic works created by Indigenous people must cater to the “imagined community” in the Canadian theatre. This imagined community is one that reflects “immigrants’ struggles in second language acquisition, and recognize, challenge, and negotiate the artistic, ideological, and performative tendencies […]” Although the Indigenous peoples are not immigrants, they are forcefully assimilated into the language and culture of Western settlement. I consider myself to be quite ignorant around the subject of Indigenous peoples, but I feel that there is truly a lack of literature and stories that simply tell of their culture, traditions, and lives. The few works I have read are all revolved around tragedies that were faced by the Indigenous peoples, including isolation, sexual violence, and oppression. These were significant works in education someone like me who did not know much about the Indigenous peoples, but at the same time, there’s a wish in me to see a piece of literature that allows me to understand the culture better. King’s Green Grass, Running Water and Harry Robinson’s Living by Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory provided a glimpse of what Indigenous storytelling might be like, what they value, and what they are interested in. I also enjoyed the creation story of Charm and her friends, which was one that was completely different from the Western or Asian creation stories I have heard.

In the beginning of the term, one of our peers shared a link to Margaret Atwood’s interview, in which she talked briefly about the importance of Indigenous publishing. This article also discusses about how working with Indigenous manuscripts “requires craft, skill, and respect” in order to preserve the stories, the understanding, and keep the words alive. Relating back to what Thien said in her speech, I do think that this is one of the small steps we can take towards lifting the limitations of Indigenous literature and artistic works—to have editors, publishers, and critics who have the depth of knowledge and appreciation required to critique Indigenous works.

-Anna (Maple Leaf Igloos)

I realized the article link didn’t work! Here is the url: https://publishingperspectives.com/2017/08/canada-indigenous-voices-in-publishing/

Hey Zhong.

I believe the article wasn’t referring to specifically indigenous people creating works that cater to “an imagined community” but specifically immigrants. What the article is trying to say, is that Immigrant Canadian theatre is partly characterized by similar themes, and those themes, tending to show or reference their homeland on stage in contrast with experiences here in Canada and illustrate their struggle to adapt here in Canada.

The “Imagined Community” is a community of immigrants with similar experiences. Shows are catered to this community rather than the “Canadian Commnity. ‘ The article is saying that this immigrant community is not reflective of a Canadian experience, because all Canadian’s can’t relate to this topic.

I am saying that we disagree with this, and that a significant number of Canadians are immigrants, and it is important to showcase the troubles to adapt in Canada. That struggle to adapt contributes to a new Canadian National Identity. By establishing that immigrant theatre is less valid and non reflective of Canadian values, we are saying that the only true Canadian must be born in Canada. Which in my opinion is insane.

Hi Voyageurs!

Thank you for this interesting, thorough, and varied bibliography. As I read some of your cited works, I was struck by the ways in which so many people and artists from diverse cultures speak of needing to create opportunities for themselves. I notice a sort of chronology of Canadian literature developing in the interpretations you have presented, whereas what was previously understood as Canadian literature was predominantly white, grounded in works by the majority, and often revolved around a sense of connection to landscape and rural spaces. Then, as Canada has diversified, you identify the ways in which Canadian literature has attempted to diversify as well, incorporating more work by immigrants, diasporic understandings of Canada, and what it can mean to be a “hyphenated creator” who engages not only in Canadian Literature/Culture but also in subgenres and niches like “Asian-Canadian” writing, “African-Canadian” writing, etc. I think some of what the authors and artists you’ve cited address is a sort of transition away from this classified style and into a more liminal space, where what is “Canadian” is largely undefined. I think the approach you’re presenting, where Canada begins to embrace diversity not only as a sort of moniker but as something with action behind its designation is really important.

I was particularly struck by the ways in which many of the artists and authors you’ve identified connect their success with ingenuity. As Margaret Jetalina identified, her success did not come from invitations to festivals, publishing offers, or agency; she had to go and create opportunities for herself. I was wondering if you could speak to the idea of self-reliance in diasporic writing and communities within Canada. Why is it that these groups must still fight to be embraced? How can we meaningfully promote the works of minority Canadians as “canon” in our literary culture? I think one potential solution is to create more funding opportunities and grants that allow individuals from minorities to finance and create their work, but these opportunities have not been prominent enough to create a holistic Canadian culture that really defines a space for diasporic works.

Hey Charlotte.

Thanks for your commentary, I think you’re absolutely right that the trend toward inclusivity is becoming much more popular these days. I do think we have a long way to go. I know specifically in theatre, it is difficult for anyone to get new work produced. It is a challenge because a significant amount of capital needs to be produced through ticket sales to make venues want to produce theatre. This is partly why traditional venues produce mainly established work from England or America. These are shows that have proved they will make money on his production. They’re safe.

The issue for new writers, white or not is new work is untested. New work that is risky or promotes a different point of view from the norm is even more financially risky. The only way to combat non-inclusivity, is to write new work, but the only way to get new work presented, is to have a wide commercial appeal. It would be wonderful if there were more programs for playwrights that assisted with funding to get plays produced.

There are quite a number of grants available through the Canadian Counsel of the Arts and through Play-writes Canada. The issue is not getting funding to write the piece, but getting established theatre to take a chance and produce your work.

I don’t have an answer to that. Theatre specifically often have trouble funding their seasons, perhaps if the CCOTA (Canada counsel of the arts) would provide full funding for new productions that have roles for non-white and immigrant actors or stories written by non white play-writes.

It is challenging when the arts keep getting defunded on a federal and provincial level. It is hard to produce new works, especially new works that contribute to Canadian identity without the support of the state.

The CBC is doing a really good job in this regard of dealing with Canadian identity in TV. A lot of CBC originals are great for showcasing new Canadian work. However, I have noticed that a lot of the work on the Canadian small screen comes from predominantly white writers, dealing with English-Canadian actors.

We’re slowly moving in the right direction, but we need to ramp up our speed on inclusivity, and part of that needs to come in the form of federal funding.

Thanks for this interesting dialogue!

It’s frustrating that there’s so little funding in the arts and specifically for supporting new and diverse theatre projects. I thought it might be valuable to share some info on a threatre company called Theatre for Living with you folks, since promoting artists can be a great way to help their audiences grow, and help them fund new works.

I saw an amazing and subversive theatre production of theirs at the Fire Hall Arts Centre called šxʷʔam̓ət (Home) which uses audience interaction to start a discussion around the question “What does reconciliation mean to you?”. This work had a powerful impact on me, not only having me see theatre in a new and more interactive light, but also opening me up to conversations about reconciliation in an atmosphere of listening and learning and sharing. Theatre for Living have posted a webcast of this production on Youtube if you’re interested in taking a look: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNvOF8sb3-A

Here’s part of the blurb from the Legacy page of their website: “Theatre for Living’s work is a worldwide leading example of theatre for social change; theatre for dialogue creation and conflict resolution; theatre for community healing and empowerment. Projects have taken place in collaboration with First Nations and multicultural communities through over 500 theatre workshops, Power Plays and Forum Theatre events around the world” (“Legacy”).

I’d love to hear about any theatre groups or productions that you folks enjoyed and would like to promote!

Works Cited

“Legacy.” Theatre for Living, David Diamond, http://www.theatreforliving.com/legacy.htm.

Theatre for Living. “šxʷʔam̓ət (Home) 2018 Webcast.” YouTube, 28 Mar. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNvOF8sb3-A.

Hi again Voyageurs,

I noticed that in addition to traditional understandings of literature, you’ve included a number of artists who bridge the gap between written and performative works. I was wondering if you think the future of Canadian literature involves not only a shift in what it means to be “Canadian,” but also in what it means to create “literature.” You highlight the need to bring diverse voices to the forefront not only in our writing, but also in popular media like television, radio, and music, as well as on the stage through plays and theatre. I found it really interesting that many of the works you identify examine theatre in particular; as theatre is so inherently public, this presents a way to showcase minority voices and narratives that also involves physically making diverse groups visible on the stage as well as behind the page. Does your future for Canadian literature require moving beyond the borders of written work in order to confront some of the limits that minority figures face in getting their work showcased? This ties into some of the discussions you’ve already had regarding the barriers and limits that minorities face in incorporating into the current definitions of Canadian work. Our group is particularly interested in borders and definitions, and I think that while we’ve looked at things like hypertextuality and paratextuality as a structural way to move beyond traditional definitions, changing the modalities we consider to be literary could also be one way of confronting the barriers that exist within our current understanding of Canadian literature.

Hello Charlotte,

We are lucky to have a theatre major in our group who is passionate about the arts.

I remember an English professor once joking about how Canadian authors become “Canadian”. She mentioned that if the author as born in Canada but soon moved away before publishing their work, Canada claimed them as their own. The same is true for authors that were born elsewhere but moved to Canada before publishing their work. There seems to be a constant need to find “Canadian” writers in order to claim some sort of culture. I think that is where our intervention strategy aligns with your idea of moving beyond borders. The diasporatic author is able to move beyond borders to bridge the gap and gain new information and knowledge of other cultures within a diverse country.

This article by Hankivsky and Dhamoon. “Which Genocide Matters the Most? An Intersectionality Analysis of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights.” is a discussion about the politics that surrounded the Canadian Museum of Human Rights. Many groups felt that they should be not only included in the museum but featured centre stage. This started fighting between groups of cultural advocates who believed that their people suffered the most in their particular genocide. It began this sort of “Oppression Olympics” which pitted victims of genocide against each other to prove who was oppressed the worst. The environment was very toxic and one that was not built on understanding. The reason why I bring up this article is because I believe that having a more diverse literary culture of works by diasporatic authors will help create an understanding with more respect. To answer your question about moving beyond borders, I think that there is an appetite to embrace globalization in a culturally diverse way. Being able to unify means that we must eliminate borders and walls that separate us.

Thank you

Hankivsky, Olena, and Rita Kaur Dhamoon. “Which Genocide Matters the Most? An Intersectionality Analysis of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights.” Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne De Science Politique, vol. 46, no. 4, 2013, pp. 899–920. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43298395.

Hi Voyagers,

You have kicked off a great topic with your blog and it was very eye-opening to listen to the video about multiculturalism failing on Canadians of Indigenous origin. I think you have opened up a very intriguing issue, because for the long time multiculturalism in Canada has been viewed through anglophone/francophone prism with complete obliviance as far as the Indigenous First Nations people were concerned. My understanding is that multiculturalism as a part of Canadian identity is being at question today regarding its purpose and inclusivity, and regarding its course going forward. What is your opinion regarding the future of multiculturalism in Canada?

Thank you in advance.

Hey Voyagers, thanks for the great read 🙂

I really enjoyed the Jen Sookfong Lee essay “Open Letters and Closed Doors:

How the Steven Galloway open letter dumpster fire forced me to acknowledge the racism and entitlement at the heart of CanLit” which you provided. Reading the title, I was originally puzzled, having know the Steven Galloway case to revolve around issues of sexual abuse and sexism in Canadian lit communities, but not having heard of it connected to racism. However, when I started the article, I remembered how interconnected these two issues are, and how progress in Can lit communities needs to be intersectional, not only addressing issues of sexism and racism, but also the places where these problems overlap. They also overlap with other forms of discrimination such as ableism, and all these problems need to be investigated together, not separately.

I was sad to hear about her feeling of disconnection and non-acceptance within the community—“I felt like the world was finally seeing what I already knew, which is that CanLit has always been heavily weighted to a certain kind of author writing a certain kind of narrative. That I, as a woman of colour who writes novels that often explore the backyard oppressions in our Canadian cities (not always a popular topic with those who would rather blindly believe there are no such oppressions), had never felt belonging”—and I was also disgusted to hear about the assault and discrimination Lee had herself experienced in her writing community, especially with our own close proximity to it as UBC students.

Thank you for your call to action at the end of this post, I think it’s really important to stand up against issues through practical action, and not simply leave these conversations in scholarly/theoretical space. Thus, I’d love to brainstorm some strategies for actively combating discrimination in arts communities with you all. A few that come to mind for me are: vocalizing our problems with offensive/oppressive behavior when we see it, not tolerating verbal or physical harassment of any kind in community spaces, even when the perpetrators are people of high status/regard within the community, and discussing what makes a space feel safe and supportive with the other members of our communities. What strategies do you think might be effective?

Hey Alexis.

Thank you for your well thought out and well written commentary. What a great article on Prince Hamlet! I always think it is super cool when we can revitalize a work, especially Shakespeare, to fit our current time. The fact that they are making the piece bilingual (English and Asl) shows promise of inclusivity. It is becoming increasingly popular for directors to engage in colour and gender blind casting. In 2010, there was a film production of The Tempest which cast Helen Mirren, as Prospero, traditionally a man’s part.

Theatre productions are certainly heading toward inclusivity, but the problem remains that the majority of well known Canadian productions being written cater to mostly white actors. I think adapting old theatre to become more inclusive isn’t a bad thing, but I do believe more new original work needs to be written that reflects Canadian stories that are inclusive.

I believe part of the reason for this is that white play-writes are uncomfortable writing outside their race. They don’t want to offend anyone with ignorance, and in doing so simply just propagate the problem un-knowingly. It’s a problem, I don’t necessarily have a solution for, other than to encourage play-writes to do research, and petition the Canada Counsel of the Arts, for new funding for play-writes of colour.

It is frustrating when the National Arts Counsel won’t even fund established indigenous theatre programs.

Hi Voyagers, it is Dana from Maple Leaf Igloos.

Out of the thoughtfully gathered collection of annotated works that you presented us with in your blog, one that really resonates with me is the story of Jen Sookfong Lee. This rarely talented and profoundly intelligent writer has been harassed by the editors’ establishment that set up their own norms and bring lump sum considerations on what Canadian readership wants to read. Not only that she has been asked to bend her literary style to cater for certain ethnic audience in Canada, she has also been exposed by demeaning chauvinistic comments for being a woman of Asian origin. How did it come to this? What happened with multicultural platform that we have all been so proud of? What about women’s rights when it comes to this particular writer? What about Equality Rights as laid out in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms? I wonder if anyone would like to comment?