A work in progress (me)

by rebecca ~ November 6th, 2010. Filed under: Ordinary Miracles, Poems & art.REMEMBER THIS

4 a.m. She’s awake, taking notice. A hollow, repetitive thud of water tumbles, one poorly insulated wall away from her head, from the clogged gutter down onto a plastic cover caulked over the basement window. She remembers to tell the landlord to clean the gutter. By morning she’ll forget. She turns a fan on to cover the sound. The fan is loud. She puts in earplugs. She hears her inhalation-exhalation, her ear drums throb with heartbeat.

She thinks of leftover lasagna in the fridge, but puttering in the kitchen to reheat it might wake her son. She reminds herself to get ant poison. A colony invaded the kitchen a month ago. Underfoot, they swarm in tight frenzied units, glomming onto any stray crumb or juice splash they find.

Her son lately draws ant-sized drawings of ants at the top of his homework sheets. “Dirty ants” or “Ant City!” he shouts. Her son doesn’t talk much. Deep in thought, he draws pictures in the air with his fingers. She is always asking what he’s drawing. Once it was his school’s elevator. He’s allowed to ride it only on Tuesdays, when the speech therapist takes him to the resource room. A passion for riding that elevator and his devastation at it being denied taught him one key to survival in this life: “Sometimes yes; sometimes no.”

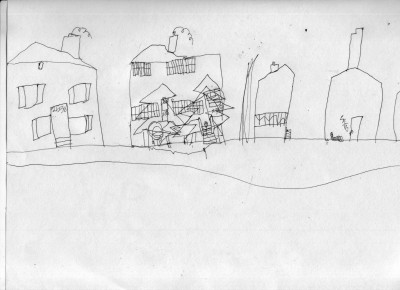

Once he said he was drawing the neighbors’ houses, so she gave him a piece of paper. He drew each window, door, house number, pointing out to her which homes had “tall chimneys.” The next day she walked to the bus stop and looked at the houses with new eyes. This epiphany happened around the same time he began peering after nightfall into the neighbor’s kitchen facing theirs. Her son began darting outside without warning to try to tug open the neighbor’s front door. Finally, to appease him, accompanied by Dad, he asked the neighbor the question she had taught him, “May I come in for a minute, please?” Through the kitchen window, she saw him zigzag through the neighbor’s kitchen, his face wild with unbridled joy. He momentarily froze at the window facing her. They saw each other clearly lit in the dark windows, separated by only six feet of night.

Her neck aches from the angle she props her head against the frigid wall. It’s mid-May and the rain could turn to snow. Early this evening her son leapt like a nutty grasshopper in the rain as she tugged a bed sheet over the strawberries and carrot sprouts. Unexpected weather sends him into a dance of abandon. What part of the human soul allows any person to feel this happy, this free?

Tonight before she tucked him in bed, she asked him what sentence he was writing out furiously with his finger. “I will save the earth,” he told her. When future experts state their assumptions again about her son’s disabilities, she wants to remember this sentence, hold onto it like a smooth, sun-warmed stone. She’ll spell the words out with her finger in front of their faces. She’ll spell it over and over in the distance between their startled faces and her own toothy smile. The experts will glance down, feign notes, doodle, hold their emotions in check, and ponder how to broach the delicate subject of therapy for a mother gone mad.