“Each student should select a section of Green Grass Running Water approximately 10 pages. The task at hand is to first discover as many allusions as you can to historical references (people and events), literary references (characters and authors), mythical references (symbols and metaphors). While I am suggesting a method to help organize your task — you should quickly discover that there is no method for making neat categories out of King’s numerous (and humorous) allusions and references. Instead of categories, what you will discover are connections, and inter-connections and cycles.”

Selection: Green Grass Running Water (1993) by Thomas King, pages 149-159

The passage I selected spans four scenes, exemplary of many of the themes King explores throughout GGRW: the harmful narratives told through Western films; white society’s attachment to Indian tropes including the mythic and stoic Indians; popular culture and literary portrayals of Indigeneity since colonization; the means through which white folks claim superiority over North America, as well as the ways Indigenous women use their voices to challenge white, patriarchal power and dominant narratives of conquest.

The storyline is cyclical and non-linear. Throughout the passage, stories are interwoven with one another. To simplify my analysis, I have divided the stories by scene of which there are four, just as there are four sections in the book, four seasons, and four Indians- First Woman, Changing Woman, Thought Woman and Old Woman.

Charlie Looking Bear goes to Blossom, Alberta

The passage begins with Charlie’s arrival to Blossom, Alberta where he is renting a car. The name of the fictional Blossom, Alberta, according to Jane Flick, “suggests natural beauty and regeneration.” (Flick 147).

The car rental clerk tells Charlie that “There were old Indian ruins and the remains of dinosaurs just to the north of town and a real Indian reserve to the West.” (King 149), equating Indigenous people with dinosaurs (the dead Indian trope), while also mystifying the Indigenous community to the West by affirming their “real”ness and emphasizing that their place is “over there” rather than inclusive of the territories beneath their own feet.

In Charlie’s narration he refers to the tourism materials the clerk offers Charlie as a “Welcome-to-Blossom litter bag” (King 149), perhaps alluding to the wastefulness or the sham that is and has been settler place-making on Indigenous lands.

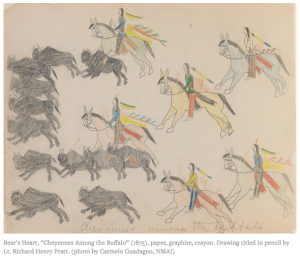

Bear’s Heart, “Cheyennes Among the Buffalo” (1875), paper, graphite, crayon. Drawing titled in pencil by Lt. Richard Henry Pratt. (photo by Carmelo Guadagno, NMAI)

When Charlie goes to collect his rental car, all he finds is an old rusted, red vehicle- the Pinto. The name is a play on Christopher Columbus’s ship, the Pinta, as well as a “Ford automobile. Plains horse. A piebald or “painted” pony associated with Indians of the Plains.” (Flick 146). Flick also notes that Pinto horses are prominent in the drawings Alberta describes in her lecture about the Cheyenne who were imprisoned at Fort Marion (Flick 146).

Charlie drives in the rain, symbolic of his glum mood, to the Blossom Lodge where he checks in with N. Bates, Assistant Manager. Norman Bates is the protagonist in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960’s thriller Psycho, about a disturbed motel owner who murders his mother Norma and then begins to impersonate her in his denial of her death.

Charlie foreshadows the fate of the Pinto as he gazes out the window at the car. “The Pinto was sitting in a low depression that was fast becoming a puddle. He’d call in the morning and see about an exchange. In the meantime, maybe it would just float away.” (King 154).

This is also one of many references to the creation story which begins with only water. The many references to the beginning of creation symbolize the cycles of time, concurrent possibilities of new beginnings, and the centering of Indigenous ways of knowing.

Portland goes to Hollywood

Interwoven with the story of Charlie arriving to Blossom, Alberta are stories about his father, Portland, who was once an actor in Western films.

Iron Eyes Cody. Pollution: Keep America Beauty, Ad Council. 1971.

According to Charlie’s mother Lillian, Portland also went by the name Iron Eyes Screeching Eagle – “A ‘really Indian’ name,” (Flick 153). In Flick’s guide, she says the name is based off Iron Eyes Cody, who she says is a Cherokee actor famous for his roles in Westerns. However, Flick is mistaken about Iron Eyes Cody’s heritage. It was clear after Iron Eyes Cody’s death in 1999, that he, in fact, was not Native American, but an Italian-American born by the name Espera Oscar de Corti.

Note the size of his nose.

Appropriating Indigenous identity, unfortunately, is not uncommon- see Grey Owl (also known as Archie Belaney), Canadian author Joseph Boyden, or US Presidential Candidate Elizabeth Warren. In this podcast, Cherokee scholar Daniel Heath Justice unpacks some of the nuances regarding Cherokee identity and the ways family folktales become “truth” overtime.

C.B. Cologne, the novel’s fictional Italian whose name is based off of Christopher Colombus’s (1451-1506) Spanish name, Cristofor Colombo, appropriated Indigeneity to play Native leads in Westerns much like Iron Eyes Cody.

Cologne’s wife, Isabella, is named after Queen Isabella I of Spain, who sent Christopher Columbus to find India. When Columbus arrived to North America, he believed himself to be in India, thus the Indigenous people became “Indians.” From the perspective of Cologne’s character in GGRW, one can become Indian.

It was Cologne that suggested the name Iron Eyes Screeching Eagle for Portland, implying that the more Indian one seems according to a predominantly white Hollywood crowd, the more likely they are to get roles. The name, of course, refers to the other Italian who became Indian.

And, for Portland, it worked. His roles increased.

“Before the year was out, Portland was playing chiefs. He played Quick Fox in Duel at Sioux Crossing, Chief Jumping Otter in They Rode for Glory, and Chief Lazy Dog in Cheyenne Sunrise. He was a Sioux eighteen times, a Cheyenne ten times, a Kiowa six times, an Apache five times, and a Navaho once.” (King 151)

Flick’s analysis tells us that the “chiefs’ names are based on ‘The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog,’ a popular phrase for practising hand-writing and forming letters of the alphabet. The movie titles are good ‘western-sounding’ titles patterned on such movies as Duel at Diablo (1966), They Died with Their Boots On (1942) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964)”. (Flick 153).

Portland played Indigenous people from several different nations, spurring a reflection on pan-Indigeneity and also the harm that displacement and assimilation have caused on some Indigenous people’s connection to their specific culture, making some settlers believe Indigeneity is a singular culture.

When Portland auditions for The Sand Creek Massacre, based on the horrific US Army massacre of over 200 people in a Cheyenne and Arapaho village in 1864, he doesn’t get the role because of the shape of his nose.

The film is to star John Wayne, Richard Widmark and John Chivington. John Wayne and Richard Widmark, of course, are white Western cowboy actors. “Film historian Newman observes, Wayne came ‘to epitomize the Injun-hating screen cowboy,” (Flick 147). John Chivington, however, is not an actor but the name of the Colonel who led the Sand Creek Massacre (Flick 154).

—

Charlie thinks back to asking his mother some questions:

“Did he ever play the lead? You know, the hero.”

“He could have,” Charlie’s mother told him. “But that was back before they had any Indian heroes.”

“I mean, did her ever play a lawyer or a policeman or a cowboy?”

“A cowboy.” And his mother had laughed. “Charlie, your father made a very good Indian.” (King 150 – 151)

Charlie’s question about Portland playing “the hero” refers to the way Indigenous characters are most-often positioned in Western films- to be dominated. In Flick’s notes, she says that there was a “shift in the presentation of Indians in some Hollywood films, starting in the 1950s and becoming pronounced in the 1960’s and then again in the 1990s with such films as Dances with Wolves (1990).” (Flick 152-153). That being said, Dances with Wolves, though it had more positive, dynamic portrayals of Indigenous characters, was yet another problematic white saviour film.

Today, Indigenous-made films that centre Indigenous languages and ways of knowing, such as the first Haida-language film Sgaawaay K’uuna: Edge of the Knife (2018), are being met with excellent reception from Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities alike.

Next, Charlie asks Lillian whether Portland played “a lawyer or a policeman or a cowboy?” (King 151), a jab at the hateful settler-imaginary rife with denial that Indigenous folks can play important roles in society and be anything but “the Indian.” Thomas King’s I’m Not the Indian You Had in Mind is a further response to harmful settler-imaginaries.

Lillian’s answer, “your father made a very good Indian,” (King 151) points to policies of assimilation which have sought to produce “good Indians,” an idea based on Whiteness. Assimilative policies to create “good Indians” have included the residential school system, the day school system and the 60s Scoop, which all sought to assimilate children into white society through violent means, which included removing them from their families and cultures and beating them for speaking their languages.

A young Charlie carries on by asking Lillian why Portland left Hollywood. She ignored the questions until, laying on her death bed, she finally told Charlie: “It was your father’s nose that brought us home.” (King 151).

Alas, despite his efforts to change his name and wear a fake nose to please the settler-gaze, Portland never managed to fit Hollywood’s perception of what an Indigenous person is.

He wasn’t the Indian they had in mind.

Dinner at the Dead Dog Cafe

Latisha is anticipating diners at the Dead Dog Cafe, where she works as a waitress.

The cafe’s name alludes to ignorant tourist’s misconceptions “about traditional Blackfoot cooking,” (Flick 149). Historically, including in my own family, there are stories of Indigenous and northern folks eating dogs in times of starvation or emergency (I once heard of my grandpa, who was Ukrainian and married to a Cree woman, being stranded out with his dog sled team in the harsh northern Manitoba winter and having to eat one of his dogs). We also know that in GGRW the character Dog’s name is GOD backwards, so the name also refers to the death of a Judeo-Christian God in a place (the restaurant, the Blackfoot community) where Blackfoot ways of knowing and being can rise.

King later used the name for a CBC spinoff series- Dead Dog Cafe Comedy Hour.

Latisha sees a tourist bus arriving which she deciphers is from Canada based on the way the tourists file out, wait, and walk into the restaurant in pairs – a commentary on the stereotype of the nice, good and docile Canadian. Though these traits could be perceived as positive, they often act as settler-Canada’s mask for covert racism and violence. Justin Trudeau is an astute model of this Canadian trope (think of the ways he’s actually (not) addressing reconciliation– by approving the Trans Mountain pipeline (a decision reversed by the Supreme Court), demoting Jody Wilson-Raybould, Canada’s first Indigenous Justice Minister, failing to adequately address critical water, education and child care crises in Indigenous communities, and that doesn’t even get at the biggest question: land).

Four guests arrive to Latisha’s table. They introduce themselves as Polly Johnson, Sue Moodie, Archie Belaney and John Richardson. Their names are all based off historical figures who contributed to the CanLit canon by writing about Indigeneity – E. Pauline Johnson/ Tekahionwake, Susanna Moodie, Archie Belaney/ Grey Owl, and John Richardson.

Let me introduce them to you:

Polly Johnson was based on E. Pauline Johnson/ Tekahionwake (1861-1913) a poet and performer. Her father, who was Mohawk, died in Johnson’s 20s, and her mother, who was white, contributed significantly to Johnson’s literary education. As Flick mentions, Johnson was famous for her performances wherein she would appear in “buckskins,” however, Flick fails to mention the latter part of Johnson’s performances where she would change into Victorian garb. For Johnson, it was a demonstration of her versatility in both worlds, whereas white audience members perceived the shift as representing the seamless flow of an Indigenous woman into assimilation. Perhaps the same could be said of white perceptions of King’s photograph project with the Lone Ranger masks.

I wonder whether Johnson is included in a group with characters such as Archie Belaney because of the way she performed Indigeneity, however, we must generously consider Johnson’s complex position in society as a racialized, unmarried woman facing poverty. It is said that her performances “drew heavily on the tropes of the ‘Indian Princess’ and ‘noble savage,’” (Robinson), but she did so with a level of intention and was committed to speaking up for her people. For example, at a Young Men’s Liberal Association gathering in 1892, attended by Duncan Campbell Scott among others, Johnson recited her poem “A Cry From an Indian Wife” which ends with the lines:

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men’s hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low…

Perhaps the white man’s God has willed it so.”

Sue Moodie, based on Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) came from England to Canada in the early 1800’s, part of the colonial force the pled innocence. Moodie wrote about her experience in Roughing it in the Bush (1852), wherein she portrays “Indians as noble savages,” (Flick 154).

Archie Belaney (1889-1938) was an Englishman and conservationist. “In the 1930’s, Archie Bellamy, assumed the Native American identity of Grey Owl, to carry on a conservation message. It is said that his work saved the Canadian beaver from extinction. His British origins, his subsequent migration to Canada and his career move from trapper to conservationist were discovered upon his death.” (Ennis).

Every time someone “becomes” Indian, it mocks the legitimacy of Indigenous claims to nationhood and sovereignty.

Lastly, there sat John Richardson (1796-1852), a settler-Canadian author, who wrote Wacousta (1832), a novel about an Englishman who “becomes” the “savage” Wacousta (Flick 155). The novel’s importance has been hailed in the CanLit canon.

The guests are polite and order the special- Old Agency Puppy Stew. Flick says this is “A joke about ‘local dishes.’ Old Agency is a Blackfoot settlement on the Blood Reserve six miles from Lethbridge.” (Flick 150).

The characters go on to make subtle references to the real-life historical figures they’re based off.

Moodie begins- “With the exception of Archie,” said Sue, “we’re all Canadians. Most of us are from Toronto. Archie is from England, but he’s been here for so long, he thinks he’s Canadian, too.” (King 158). This is a jab at how Archie “became” Grey Owl. Funny enough, Moodie also erases her own roots and history of colonial settlement when she alludes to having been there long enough to think one is Canadian, as she doesn’t admit to her own European birthplace.

Then, Johnson makes an interesting comment- “None of us,” said Polly, looking pleased, “is American.” (King 158). Johnson was known to be a proud Canadian writer, but interestingly, several Mohawk territories were split by the Canadian-US border, making over 13,000 Mohawk people Mohawk, Canadian and American citizens.

Next, referring to their road trip, Archie says “We’re roughing it,” (King 158), alluding to Moodie’s book Roughing it in the Bush.

Lastly, Sue says:

“Polly here is part Indian. She’s a writer, too. Maybe you’ve read one of her books?”

Latisha shook her head. “I’m sorry, I don’t think I know them.”

“It’s all right, dear,” said Polly. “Not many people do.” (King 158).

These comments refer to the lack of platform for Indigenous women writers at the time. However, E. Pauline Johnson did receive notable attention, even touring Canada, the US and England.

When the guests leave, they leave a book for Latisha, The Shagganappi by E. Pauline Johnson which wasn’t published til after Johnson’s death, with a $20 tip underneath. Flick suggests the $20 is offered in attempt to get somebody to read Johnson’s work.

George’s thoughts on Canadians v. Americans

This scene is a flashback to memories of Latisha’s marriage to to George Morningstar.

George’s character represents George Armstrong Custer, a white settler-American from Michigan. “At 23 he was the youngest general in the Union Army; he was given command of the Brigade.” (Flick 151). The last name, Morningstar, is based on a name, ‘Son of the Morning Star,’ given to Custer by the Arikaras in Dakota territory (Flick 146).

Morningstar’s comments to Latisha, based on stereotypes, about American supremacy are rooted in patriotism from his time in the US Army.

Morningstar goes on to say: “Americans are independent,[…] Canadians are dependent.” (King 156). Americans, according to George, are also adventurous, and he uses the example of western expansion and the frontier experience as well as Lewis and Clark. Flick adds that “Clark was later superintendent of Indian Affairs,” (Flick 155).

Canadians, meanwhile, are conservative according to George. Latisha offers Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635) and Jacques Cartier (1491-1559) as Canadian examples of “adventure” and expansion, but George brushes them off as European- proving his misunderstanding of settler-colonial occupation in the US and the histories of settlement and erasure in all of the Americas.

“Latisha told him she didn’t think that he could make such a sweeping statement, that those kinds of generalizations were almost always false.” (King 156).

As an Indigenous woman, Latisha is well aware of the harm done by generalizations and stereotypes. Additionally, George’s version of history is the type that has validated domination and slavery in the eyes of white Americans. Ideas of superiority are always based on myth, false histories, and perceptions- on generalizations.

George goes on to list the “great military men in North America” (King 157) who, according to George, were all American, “most associated with anti-Indian activity,” (Flick 155).

Latisha becomes angry.

“What about Louis Riel? What about Red River and Batoche?”

“Didn’t they hang him?”

“Billy Bishop!” Latisha almost shouted the name.

George put his arms around her and kissed her forehead.

“You’re right, Country,” he said. “There’s always the exception.” (King 157)

Louis Riel, a Red River Metis, led the Metis rising and the Red River Rebellion and was eventually hanged for his bravery.

When George says, “there’s always the exception,” (King 157), he, perhaps unintentionally, takes a jab at Latisha – his partner, and the supposed “exception” to his racism, white-superiority complex and belief in colonialism.

Latisha’s ability to speak up, and eventually leave, reminded me of a story I read during my research by E. Pauline Johnson, A Red Girl’s Reasoning (1893). A Blackfoot and Sami filmmaker made a powerful film by the same name, A Red Girl’s Reasoning (2012), about an Indigenous woman who becomes a vigilante as a response to her brutal sexual assault.

In response to George’s racism and babbling, Latisha begins to avoid him, nursing her baby Christian in the bedroom where she would whisper, “You are a Canadian. You are a Canadian. You are a Canadian.” (King 159).

Works Cited

Andrew-Gee, Eric. “The making of Joseph Boyden: Indigenous identity and a complicated history.” The Globe and Mail: Profile. November 12, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/books-and-media/joseph-boyden/article35881215/

Barrera, Jorge. “Cabinet shuffle shows reconciliation dropping in priority for Trudeau, say Indigenous advocates.” CBC News. January 15, 2019. Accessed at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/cabinet-shuffle-indigenous-reaction-1.4977946

Canlit Guides. “E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake).” Canlit Guides. August 19, 2016. Accessed at: http://canlitguides.ca/canlit-guides-editorial-team/e-pauline-johnson-tekahionwake/

Caryl, Sue. “November 29, 1864 CE: Sand Creek Massacre.” Resource Library: This Day in Geographic History. October 27, 2014. Accessed at: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/nov29/sand-creek-massacre/

Catlin, George. “Sioux Dog Feast, 1832-1837.” Art & Artists: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed at: https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/sioux-dog-feast-4366

Charity, Tom. “Sgaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife).” Canada’s Top Ten: Tiff. 2018. Accessed at: https://www.tiff.net/events/edge-of-the-knife

Cinema Politica. “A Red Girl’s Reasoning.” Films. 2012. Accessed at: https://www.cinemapolitica.org/film/red-girls-reasoning

DeSouza, Mike & Meyer, Carl. “Court quashes Trudeau’s approval of Trans Mountain pipeline.” National Observer. August 30th, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2018/08/30/news/court-quashes-trudeaus-approval-trans-mountain-pipeline

Ennis, Donna. “Beware of Ethnic Imposters.” Indian Country Today. September 15, 2014. Accessed at: https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/beware-of-ethnic-imposters-8RMP43Q_WEWNqmF3etRUYQ/

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” PDF.

Gray, Charlotte. “The true story of Pauline Johnson: poet, provocateur, and champion of Indigenous rights.” Canadian Geographic. March 8, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/true-story-pauline-johnson-poet-provocateur-and-champion-indigenous-rights

Hanson, Erin. “Reserves.” Indigenous Foundations: UBC Arts. Year Unknown. Accessed at: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/reserves/

Herndon, Astead W.”Elizabeth Warren Apologizes to Cherokee Nation for DNA Test.” The New York Times: Politics. February 1, 2019. Accessed at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/us/politics/elizabeth-warren-cherokee-dna.html

Johnson, E. Pauline. “A Red Girl’s Reasoning.” Dominion Illustrated. Accessed at: http://canlit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/red_girls_reasoning.pdf

Keating, Joshua. “The Nation That Sits Astride the U.S.-Canada Border.”Politico Magazine. July 1, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/07/01/akwesasne-american-indian-community-218936

King, Thomas. “Green Grass, Running Water.” 1993. Print.

King, Thomas. “I’m not the Indian you had in mind.” National Screen Institute. 2012. Accessed at: https://vimeo.com/39451956

Manitoba Historical Society. “Red River Resistance.” Manitoba History. Spring 1995. Accessed at: http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/29/redriverresistance.shtml

Medicine for the Resistance. “Elizabeth Warren and the enduring myth of Cherokee identity with Daniel Heath Justice.” Podcast. February, 2019. Accessed at: https://player.fm/series/medicine-for-the-resistance-2436734/elizabeth-warren-and-the-enduring-myth-of-cherokee-identity-with-daniel-heath-justice

Meier, Allison. “A 19th-century Cheyenne warrior’s drawings of his life as a POV.” Articles: Hyperallergic. February 26, 2016. Accessed at: https://hyperallergic.com/273434/a-19th-century-cheyenne-warriors-drawings-of-his-life-as-a-pow/

Robinson, Amanda. “Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake).” Canadian Encyclopedia. July 8, 2016. Accessed at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pauline-johnson

Waldman, Amy. “Iron Eyes Cody, 94, an Actor and Tearful Anti-Littering Icon.” The New York Times. January 5th, 1999. Accessed at: https://www.nytimes.com/1999/01/05/arts/iron-eyes-cody-94-an-actor-and-tearful-anti-littering-icon.html